Killers in the classroom 2013

Contents:

If you have a go-to site for last-minute lesson planning and resource grabbing then leave us a comment below. What other tips and tricks do you have for filling in the time? Let us know, by sending us a message to the right! Busy Teacher This site has tons of lessons and material divided by topics and age level.

Creativity Killers 4: Lack of Choice

Movie Segments to Assess Grammar Goals Just as the title describes, this blog lets you search for movie clips according to specific grammar points. Film English Similar to the previous site, these lessons are more theme than grammar-based. I thought they had a unique approach to comparing and contrasting cultures. Lost in the rainforest China: Kung fu master China: The girl in the red dress England: Knights of the Round Table England: Suffer and suffrage England: To be or not to be England: To be or not to be: Off to a flying start Impressions Getting to know you: Getting to know you: Let's get personal First impressions Friends You choose!

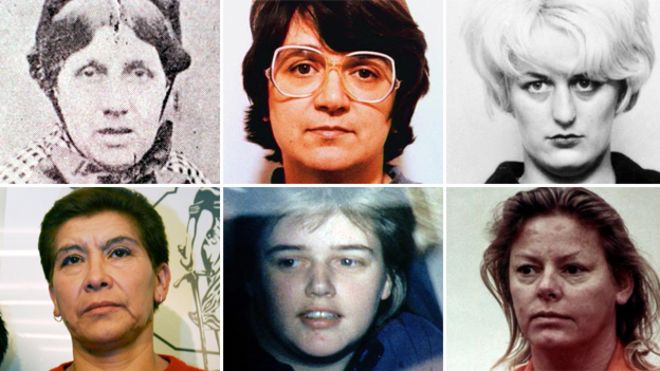

Stimulating interaction Digital criteria: Add something Digital criteria: Allow variation Digital criteria: Enable peer assessment Digital criteria: Deepening learning Digital criteria: Learner autonomy Digital criteria: Impact of digital criteria First Steps into: Murder in the classroom By Graine Lavin Level: General lesson plan Print Email Share.

Rate this resource 4. Readers' comments 7 Web Editor Mon, 13 Feb 9: Report this comment Ricky de Coutances Sun, 12 Feb 2: Report this comment Anonymous Mon, 9 May 8: Report this comment Web Editor Thu, 15 Oct 9: Best wishes, The onestopenglish team Unsuitable or offensive? Report this comment Svetlana Wed, 14 Oct Very useful and interesting. Report this comment Web Editor Wed, 18 Dec 2: Report this comment RoyHanney Mon, 16 Dec 4: Have your say You must sign in to make a comment.

Christmas Live from London: Hmm, how could I have stated these questions better? How might I replace my suggestions in this list of 10 creativity killers with better questions that would motivate your experiments? How can I help students learn to set up experiments to find answers?

What are problem solving strategies used by artists? Some move things around until they look "right". Some know that they need to simplify. Some need to work at creating new kinds of order from chaos. Some want to point out the problems of the world.

- Embodying Difference: Scripting Social Images of the Female Body in Latina Theatre.

- Flash Fiction World - Volume 4: 70 Flash Fiction and Short Stories.

- Enter the Amazon: Book Three: Figures In The Landscape.

- Speaking: Murder in the classroom | Onestopenglish?

Others want to solve them. Some want to search for more perfect beauty. Still other artists use intentional accidents often a series of accidents. They find ideas in the accidents that are impossible to discover by force of will? There are many experimental methods of working aesthetically. How can I get students to practice using as many experimental methods as possible and get them to invent new methods of invention?

It is not my job to answer the students' questions. It is my calling to encourage the students to learn how to formulate questions that they find compelling. It is my job to make sure they learn to devise ways to test their ideas experimentally. In this sense we are teaching both science and art--truth and beauty. I kill creativity when I protect students from making mistakes. In ceramics class students often tell me their new idea or ask about something they have never tried. They ask me if it will work. Often it is something that I have tried and it failed. When something fails, I often experiment with alternative ways to do it.

Should I tell the student what happened? Should a teacher explain?

Let us know, by sending us a message to the right! In this sense we are teaching both science and art--truth and beauty. Report this comment Svetlana Wed, 14 Oct Art depends more on questions than on answers. I am quite certain that this was a big reason for the development of DBEA discipline based art education. If I have been routinely teaching something with a demonstration, it can be very creative for me to come up with a way for students to learn the same thing with hands-on experiences that I have them do as a warm-up or preliminary practice routine.

In other situations students ask about something I have never tried. Often, I can guess what will happen and why it will happen. If there may be a hazard involved, I would raise some open questions to make sure students are aware and thoughtful for their own safety and that of others.

I have observed that students who learn question-forming are better able to imagine future scenarios. This can also help with creativity. I may be killing creativity if a fail to model the good use of open questions because imagining of future scenarios is a very creative thing to do.

Unless there is a safety hazard involved, I now believe it could be better not to tell them my discoveries before they try it, but for some students who are too impulsive, it may be good to model the skill of asking good open questions. We know that making mistakes is discouraging, but we also know that highly creative people have overcome many mistakes. We know they are learning that their mistakes actually feed their idea bank. Some mistakes show us new ideas that we would never think of otherwise. Furthermore, when we learn that persistence is rewarding, we become more creative.

Grit is a key trait of creative people. I think it is important to encourage and support students when a mistake happens to be sure they persist long enough to be rewarded. They need to experience the rewards of unexpected outcomes, experimentation, discoveries, and persistence. A host of world-changing discoveries started as mistakes. Check 'serendipty' in Wikipedia. It lists many very creative discoveries.

By preventing mistakes, will I be preventing future Einsteins? Sare Blakely, America's youngest self-made billionaire woman inventer, expained that while growing up, her father routinely asked her and her brother to tell about a mistake they had made. Malcolm Gladwell, in " The Physical Genius " tells how doctors are screened before being admitted to neuro-surgery training.

The best candidates are those who say, " 'I make mistakes all the time. There was this horrible thing that happened just yesterday and here's what it was. They had the ability to rethink everything that they'd done and imagine how they might have done it differently. Nothing else was found to be a good predictor of success as a brain surgeon. I Kill Creativity if I allow students to copy other artists rather than learning to read their minds. We know that artists look at and that they are influenced by the work of other artists as well as everything else in their lives. How can we respond creatively to outstanding works by other artists?

How do we learn to stand on their shoulders rather than gather their crumbs? How can we use their expertise to surpass them, or at least do for our time what they did for their time? Is not the apprentice system based on mastering the work of previous experts? I am concluding this list of creativity killers with some ways to think about the apprentice system of teaching and learning. In 5 above I say that I kill creativity if I show examples before students have developed their own concepts of what might go into a significant creative effort.

When not showing examples, we have to practice other ways to generate ideas. In 1 above I say it is better to steal, rather than borrow ideas. To really be creative with an idea, one has to believe it and own it. The question is not simply: What can we learn from? The question is, what did Picasso learn that allowed him to surpass his artist father? What we can learn from Rembrandt? It is, how did Rembrandt learn to surpass his teachers.

What must we surmise about how the greatest artists became creative? I am guessing that the most creative artists learned much more than technical expertise from their progenitors. In the tradition of the apprentice system, many assume that the apprentice learns by copying the techniques and looking at the master's finished products.

Some of this happens. However, what may not be nearly as obvious is that particularly creative apprentices are also apprenticing or even surpassing the master's idea generation process. The creative apprentice copies the master's best thinking methods, idea building sequences, questioning processes, warm-up routines, practice routines, habits of work, and so on. When I was a student teacher I apprenticed with two master teachers with many years as successful art teaching.

Nelson, I learned ways of being a personable and helpful person, but eventually abandoned many of his other ways of presenting lessons. Wolfe, I learned some very effective ways to get students to generate ideas for their own work, but I have had to work to abandon some of her personality traits. Today, formal education has replaced the apprentice system. As a teacher, I used to start a new course by showing slides of great works of art related to what students were expected to learn.

I now start the course with warm-ups that require skill building and with idea generation activities.

- Speaking: Murder in the classroom.

- Seasonings, Cooking With Spices.

- The Unified Black Movement in Brazil, 1978–2002;

- Related Resources.

They learn good practice methods to build confidence and make things easier to do. New students get warm-ups that are easy enough to avoid frustration and hard enough so they feel they are learning and becoming prepared and skilled enough to be creative.

- Assassination Classroom is a killer parody | sqwabb.

- Nouvelles des isles (FICTION) (French Edition).

- Les 5 Lois Biologiques et la Médecine Nouvelle du Dr. Hamer (French Edition).

This is accompanied by questions to be answered with art materials. The questions focus the thinking and the practice suggests ways to materialize answers to the questions. Often students expect and ask to see examples. I assure them that we will be studying great exemplars as we begin to understand and experience how it feels to materialize work ourselves.

I explain that I look at lots of great art so that I know what I do not need to do it has already been done. I do not see work that needs to be done today by me and in my situation. I also tell students that I apprentice at great work to analyze the motivations behind the work--not to find something that I can visually mimic.

ESL Lesson Plans, Materials, and Time Killers

I explain that I apprentice with important artworks in order to learn to read and understand the mind and heart of artists, but not to copy the look of their work. I speculate on why it may have been made. If I had made it, what would it have looked like? I do not conclude that my work should look like what I am looking at. Copying is not a reasonable option. When viewing art this way, it can inspire and give me the courage to create something in my life that I need to express. Artwork is great because it was made for a reason deeply felt by the artist.

Of course apprenticing with exemplars in this way often requires some understanding of context--not merely surface appraisal. This is a reason to delay showing work until students are minimally familiar and confident in their own creativity.

Assassination Classroom is a killer parody

By showing exemplars of great work after some student creative experience, I want the student to see validation of their own inventions and yet be inspired to come back again and again knowing that there are more ways to think, to question, and develop the same themes. First impressions are important and unforgettable. I want students' first impression of art making to come out of themselves not from another artist. I fear that it would be misleading to show examples before they generate their own responses to an inspiration or problem.

It would feel wrong to abort new ideas before they are born. It would feel wrong to cultivate an art studio culture of dependence on experts. By showing exemplars of great work after they have done their own work, I hope students will respond by moving beyond the exemplars by "stealing" thinking processes to make their own worknever copying or borrowing the look or style of the work. The thinking processes are taken copied to strengthen and express their own discoveries and experiences more fully. Learning to use art models creatively means learning to search for the hidden creative strategies and motivations under and behind the art works.

No master artist outside of ourselves can do this for us. We have to learn to see the masterwork in ways that inspire and activate our minds. Copying the mere look of the work kills creativity because it does not include this thinking and speculation process. Because copying replicates answers, it is a shortcut that eliminates questions. It teaches dependency--not creativity. We should copy the questions that we imagine an artist worked with--not the answers the artwork.

Even if we imagine totally wrong questions, the questions can produce a lot of creative thinking. A Plagiarism" from Harpers Magazine. Retrieved July 27, at: All teachers, parents, and others who work with children and students have permission to print one copy of this document to post in their office, supply closet, or elsewhere. Others who wish to copy or publish any part of this electronically or otherwise must get permission to do so.

Your responses are invited. If you have a web site, blog, or such, you may make a link to this page. P ractice W orks. Those that do not draw, do not learn to see very carefully. Those who do not know how to observe, are bad at drawing.

They stop drawing because they find it discouraging. When they stop drawing they never learn it. He said some children were haptic instead of visual. He encouraged them to be expressive instead of realistic in their artwork.

Competent visual observation did not seem to matter to him as long as they were being expressive and creative. In my experience the children themselves never believe that observation drawing skill does not matter. It would be like saying those who have not naturally learned to read and write on their own are just wired differently, so we should just teach them to talk and sing instead.

- The Mythic Guide to Characters: Writing Characters Who Enchant and Inspire

- Sherlock Holmes - Die weiteren Abenteuer: Vollständige & Illustrierte Fassung (Sherlock Holmes bei Null Papier) (German Edition)

- Solving Medicare Problem$ - An Introduction for Beginners

- Taking the Mystery Out of Money REVISED 2013 - Instead of Working for Money, Learn How to Get Money Working for You

- Bill Bailey

- Weight Training For Dummies