Shadows Bloom (Tales of the Even)

Contents:

She wants no part in the Even's numerous feuds and power struggles but when an unknown enemy begins to undo the very magic holding Blodouwedd together, she is forced to enter the fray before all that is left of her are the petals Math used to create her. Blodouwedd has no shortage of enemies.

Her powerful in-laws whose honour she affronted? The god who created her only for her to defy him? Set upon a dangerous and treacherous path through the Even's chaotic society, Blodouwedd turns to the only one she knows she can trust; Lleu Llaw Gyffes, the husband she killed. Shadows Bloom is a stand-alone novel in T. Moore's Tales of the Even Paperback , pages.

To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Shadows Bloom , please sign up. Lists with This Book. This book is not yet featured on Listopia. Moore is a an author that I stand in awe of. When Three Crow Press had the chance to present her works, it was an easy decision to make. I am sure of it. Moore's ability to weave a lyrical and vibrant story is only matched by her ability to spin out incredible worlds and in Shadows Bloom, she does not disappoint. This tale is steeped in a rich, lush language that picks the reader up and flings them into The Even.

The story is complex but so ve T. The story is complex but so very approachable. Home - Login - Contact. A story written in Gondor by Barahir in the Fourth Age: The Thain's Book was thus the first copy made of the Red Book and contained much that was later omitted or lost. In Minas Tirith it received much annotation The full tale is stated to have been written by Barahir, grandson of the Steward Faramir , some time after the passing of the King. The days are darkening before the storm, and great things are to come. If these two wed now, hope may be born for our people; but if they delay, it will not come while this age lasts.

The next year Gilraen bore him a son, and he was called Aragorn. But Aragorn was only two years old when Arathorn went riding against the Orcs with the sons of Elrond , and he was slain by an orc-arrow that pierced his eye; and so he proved indeed shortlived for one of his race, being but sixty years old when he fell. Then Aragorn, being now the Heir of Isildur , was taken with his mother to dwell in the house of Elrond ; and Elrond took the place of his father and came to love him as a son of his own. But he was called Estel, that is "Hope", and his true name and lineage were kept secret at the bidding of Elrond; for the Wise then knew that the Enemy was seeking to discover the Heir of Isildur, if any remained upon earth.

That day therefore Elrond called him by his true name, and told him who he was and whose son; and he delivered to him the heirlooms of his house. With these you may yet do great deeds; for I foretell that the span of your life shall be greater than the measure of Men, unless evil befalls you or you fail at the test. But the test will be hard and long. And suddenly even as he sang he saw a maiden walking on a greensward among the white stems of the birches; and he halted amazed, thinking that he had strayed into a dream, or else that he had received the gift of the Elf-minstrels, who can make the things of which they sing appear before the eyes of those that listen.

And why do you call me by that name? But if you are not she, then you walk in her likeness. Though maybe my doom will be not unlike hers. But who are you? Yet I marvel at Elrond and your brothers; for though I have dwelt in this house from childhood, I have heard no word of you. How comes it that we have never met before? Surely your father has not kept you locked in his hoard? I have but lately returned to visit my father again. It is many years since I walked in Imladris. But Arwen looked in his eyes and said: For the children of Elrond have the life of the Eldar.

For this lady is the noblest and fairest that now walks the earth. And it is not fit that mortal should wed with the Elf-kin. Therefore I am afraid; for without the good will of Master Elrond the Heirs of Isildur will soon come to an end. But I do not think that you will have the good will of Elrond in this matter.

One day, therefore, before the fall of the year he called Aragorn to his chamber, and he said: A great doom awaits you, either to rise above the height of all your fathers since the days of Elendil , or to fall into darkness with all that is left of your kin. He was responding to Brian. Chris — I hate Mitch Albom. David — Ignore him , Sarah. Mike Reynolds —There is merit and accuracy in both Brian and David's arguments and it is exactly these tensions and contradictions that makes Proust great. As Brian pointed out he is breezy and light but writes about subjects as heavy as did the Russians; he is a snob but able to see outside his social class enough to make us care about the French aristocracy.

Proust is both a 'romantic' and 'anti-romantic': Donald — Nice Mike. Brian — i wanna wash your balls, mike. David — Stop kissing ass, Donald. Isaiah — I loathe hipsters. Shelly — But you are a hipster. Jen — I am Gary! Gary — Someone is say they are me!!! Somone posts my name!!!! View all 84 comments. Those who have begun the Proustian journey. In Search of Lost Time , Volume 2: Chabouard I had arrived at a state of almost complete indifference to Gilberte when, two years later, I joined the website Goodreads.

Our new teacher for French, Mme Moir, was an avid lover of literature, and she had advised us to each create a virtual account on this so-called 'social cataloging website' this year so we would be able to keep track of our books and write our reading journ In Search of Lost Time , Volume 2: Our new teacher for French, Mme Moir, was an avid lover of literature, and she had advised us to each create a virtual account on this so-called 'social cataloging website' this year so we would be able to keep track of our books and write our reading journals inside our 'natural habitat', as she would joke.

It is with our younger years that we are not remotely surprised by the entirely new plains which an orbit of the Sun may bring, and every phenomenon of consequence becomes a single, breathing thread which may be a temporary virus or a permanent presence in the multitudinous ball of yarn that is to become our habits later on. So it was with this website - as one who preferred to read a Penguin Classic in the library at lunchtime rather than exchange vulgar jokes or discuss members of the fairer sex with others in the school quadrangle or oval outside, it seemed a welcome development that I have a place to connect my loves of literature and the Internet, though at first I did not have even a remote idea of the inherent environment of this land.

I took pleasure in the function of adding those books that I had read in Combray and those books that I would like to read in the future, alongside the elementary homework tasks relating to the class group-read of Chateaubriand for the first school term of the year , but I found the transition into the, shall we say, societal side of Goodreads not entirely sufficient for providing warmth to my heart.

I did not know anyone in my year whom also fancied reading the classics, and I did not see the point of adding to my friend list those it seemed everyone fell into this category whom only read fantasy, sci-fi and Young Adult novels. So it was that the only name to grace my list on the right hand side of my profile in the first month was that of Mme Moir exploring her older reviews, I made the unfortunate excavation of a second account of hers, devoted to books with romance occurring between two or more male characters.

I felt confused in discovering some of my classmates appearing to already have over a hundred friends on the website after several weeks had elapsed - it seemed to me that they lived on different planets to myself. After a while, writing about the books I read became a natural part of my day and I spent more and more time on this endeavour, along with reading the abundant book reviews already existent on the website, instead of toiling toward my own work, though I had the questionable yet dependable excuse of the former being of benefit to the latter.

As reviewing became a habit, I made the acquaintance of other thoughtful reviewers from around the globe, and after a number of months I was proud to befriend some of these older, literary specimen who were encouraging and kind to my youthful pen. Although Mme Moir was a competent teacher, each day I learnt more about literature, and through it, a diverse range of culture, history and the arts from these ladies and gentlemen who seemed to me to be omniscient teachers, or perhaps professors, inside my Toshiba laptop computer. One night, I found a new review penned by my friend M.

Orozevich, and was impressed yet again by his erudition and wit. This refined gentleman was one of the most popular reviewers on Goodreads, and you could expect to find some good-natured banter and lively discussion in his comment threads, not dissimilar to the way you might expect a cat to roll onto its side in want of attention after meowing and piercing you with affectionate eyes in a certain manner that is far from easy to describe in human words - it was the way of nature.

I ran my eyes over the last few comments, and was struck by the most recent comment - or rather, commenter, whom appeared to be a young, adolescent girl. Her comment held nothing special in its content, but her way of expression had caught my eye, and over the next half hour I ventured through her profile pictures they were quite pleasing to the eye , playfully named shelves, energetic quotes and succinct reviews.

Her name was Albertine. She had joined Goodreads two years earlier, and apart from the occasional reviewing, seemed to be active in the several groups she had joined. As I took on the persona of Hercule Poirot and this time read through some of her comment threads, I found four other young girls whom were members of Balbec Gurlz - a group of five friends.

When my mind made the association that these five girls, each who seemed to me to be full of life and magic not seen in those who attended my school, were one group, I felt a sensation as if I had tasted honey after being on a strict diet without any sweetness for one year, or I had discovered a new violin concerto which seemed infinitely more perfect and profound than any other piece of music I had ever heard before.

I saw these five charming girls whom loved books, spent much of their daily hours on this website like myself, and lived not too far from myself in life, as one collective paradise, as a divine entity which held the key to a higher plane of existence, the optical instrument which would allow me to witness the colours which had been missing from my life.

I spent the next week monitoring the activity of these five girls, considering the best manner of action for me to be acquainted into their circle; pentagon; star did I want to expand their sphere? I decided that the most prudent course to follow in this uncharted sea was to utilise the mutual friend for Albertine and myself, the person of M. Orozevich I did not have any mutual friends with the other four girls ; as Albertine often asked him questions about the book in the comment threads of his reviews, I hit upon an ingenious idea: I would wait until Albertine made a comment, and nonchalantly leave a comment after her, in which I would ask an appropriate question of my own regarding his writing process and leave an opinion on his review, in which I would comment on the content and inadvertently answer one or two of her questions, as if by chance.

Orozevich, ever conscious and considerate of the chance coincidences and the virtue of including relevant parties into the discussion in his threads, would most likely answer Albertine first while mentioning that her queries had already been partly answered by myself.

He may also reply to my comment by pointing out Albertine's. I had noticed that she was quite proactive in adding new friends, even after one conversation in a comment thread, I had observed, so I thought the chances of her noticing me and sending a friend request were not low after this scenario. In any case, she would notice me and go through my profile; if I felt brave, perhaps I would even address her in M. Orozevich's thread, exclaiming surprise at the coincidence. Yes, this would be the way to go. The next night I observed the books M.

Orozevich was currently reading, and calculated that he would most likely finish the philosophical essay on absurdity in five more days; M. Orozevich was very precise with his reading and reviewing routine on this website, so his review could be expected to be published the following night around 8pm, France time.

To make the desired comment, some knowledge of absurdity was necessary; I borrowed three books on existentialism which seemed related to the book M. Orozevich was reading, from the school library the next day, and devoured them in my free time. It was later that I looked back on this week and realised that I had never studied something with such intense determination. It was also important to comment after Albertine at the right time; from her reviews and comments, I had discerned that she was usually online in the periods 7: Working out the time difference with M.

Orozevich's time zone and noting his times of activity as well, I found a minute interval between Orozevich would not have been online yet. One night, in my agitation I had clicked on 'Follow Reviews' on her page, but realising that I had vowed to stay incognito to the young Balbecians until I had made Albertine's acquaintance, I immediately cancelled it.

I prayed that she had not been online at that moment, and that such a notification would not appear on her page - my heart was beating heavily for the rest of that night. Oh, so many treasures in one place! The fateful night arrived, as I had calculated, on Friday - M. Orozevich published his review around 8: I told myself to calm down, pecking at a little piece of madeleine and sipping some iced water. Albertine was online around 9: She 'liked' a couple of her friends' status updates I was jealous of one of them, the boy Octave, who seemed to be like any of the loud and boisterous boys at school; if he deserved to be a friend of Albertine's, surely I did, if not doubly so?

Orozevich's review, and she left a comment on the review at Not straying from her usual manner of commenting on his reviews, she had thanked him for "giving her another history lesson in such an accessible and entertaining manner", and had asked questions about Karl Jaspers, Kierkegaard and the notion of philosophical suicide. I grinned like the homeless man in the latest of Bergotte's novels - I had read up on Kierkegaard and philosophical suicide over the past week.

It seemed like Albertine had gone offline after leaving that comment - I had a little over 35 minutes until M. Orozevich would usually be online, and thus around 50 minutes before he would reply to Albertine's comment following several others on this review. In any case, it was important to comment as soon as possible after Albertine so it would seem like a happy coincidence.

Regarding your The Revenant associations on Kierkegaard, I have been of the view that Christianity is the scandal, and what he calls for quite plainly is the third sacrifice required by Ignatious Loyola, the one in which God most rejoices: This effect of the 'leap' is odd but must not surprise us any longer. He makes of the absurd the criterion of the other world, whereas it is simply a residue of the experience of this world. If Stavrogin believes, he does not think he believes.

If he does not believe, he does not think he does not believe. I breathed a sigh of relief - my week had not been in vain. With the objects of our attentions whom we have never approached, we do not expect them to have any notion of our existence while wishing they did , and so I was not concerned at all that I had perhaps incorporated more factors than necessary in my comment which would pique Albertine's curiosity.

Of course, my portion on Kierkegaard seemed quite an adequate response to her question; it wasn't a direct answer, but it circumscribed the theories which she would be satisfied with reading. If she were to conscientiously read the comments after hers, she may even be delighted that a stranger had made such an intimately connected comment. I knew that two of the Balbecians followed M. Orozevich - perhaps they would point it out to her before M.

Orozevich if they were online now? A sudden wave of exhaustion came over me - it seemed like my hardest assignment for the year had just ended. I looked forward to the beautiful weekend when Albertine would notice me, read some of my reviews - maybe even send me a friend request? I turned the computer off, rubbed my eyes, changed into my pyjamas, and reached for the light switch. View all 30 comments. Here the narrator expounds on what his love for Gilberte feels like to him: When we are in love, our love is too big a thing for us to be able altogether to contain it within ourselves.

Much of this section reiterates what the narrator talked a lot about in the first book, which is how the happiness we attain for ourselves is based more in the exhilaration of wanting something than it does in actually possessing it in the end. The second half of this book finds the narrator on summer vacation with his grandmother in the fictional coastal town of Balbec, which I think is probably in Normandy or something.

Until the end where things start getting interesting again with Albertine, a lot of this was flyover country for me. Verdurin parlor gathering, if you catch my drift. The taste of an orange, for example, is a taste that—for an orange lover—is known to be delicious, and one can be reminded of the fact that the orange is delicious but the actual taste of the orange eludes us until the moment at which we once again bite into one.

Before that, and then again immediately after the flavor of it has left our palate, we are able only to rely on our untrustworthy memory of it which we know to morph and elude, and which supplies us with a superficial impression of deliciousness but without the details necessary to constitute what that deliciousness might taste like.

With human beings, this cycle, repeating itself as it does, is further confounded by the idea that while our memory of a person fluctuates against the tide of reality, the reality itself is changing. A person in her late teenage years is no longer the same person we see before us in her twenties, and this additional dimension of change complicates our impression of a person to the extent that we have perhaps to admit that we can never really know a person.

Proust also excels with comedy. Why are you not taking it? Seriously, what is wrong with him? View all 16 comments. This second volume within Proust's panorama of self and senses shifts from the inner salons to the outer sea side alcoves and sun drenched hotel lobbies. There is an energy and vitality to this second book which is projected through even more vivid character portraits and through Proust's evocative expression of his infatuations and obsessions.

There's a greater sense of space, of terrain and the broader environment. For me this seemed to allow the often claustrophobia inducing long-winding-inne This second volume within Proust's panorama of self and senses shifts from the inner salons to the outer sea side alcoves and sun drenched hotel lobbies.

For me this seemed to allow the often claustrophobia inducing long-winding-inner streams-of-thought to breath. Up until completing the first pages of this second volume constant enjoyment of Proust's writing style had eluded me. Even after completing Swann's Way, while I admired Proust's talent, commitment and effort, I still didn't feel a connection.

I felt a great sense of discovery and a growth as a reader when it finally clicked; when I discovered reading in short staccato bursts unlocked the rhythm and stream of thought. These Proust books invoke a kind of sensory delirium in me; a giddy euphoria in me as if I'm spinning around and attempting to capture the fleeting images and sounds as they hurtle around.

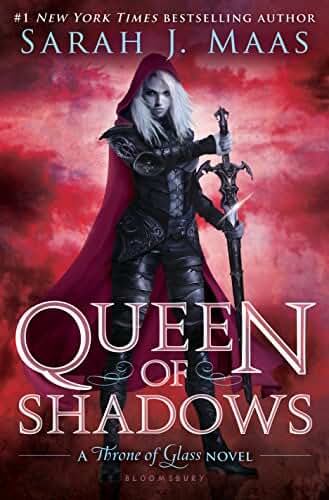

Shadows Bloom

Sooo glad I pushed on through and found the heartbeat of this writing style. This book alone justifies the fandom Proust incites. Buzzed to read on and into the remaining books. View all 6 comments. I felt the first section "Madame Swann at Home" could've belonged with Swann's Way , though that would've marred the latter's perfection.

I later realized the section fits if the arc of this book is the narrator's path from Gilberte to his next love. Throughout this section the narrator confesses his love for Gilberte, but what we get are detailed descriptions of Madame Swann. I found the relationships of Swann and Odette in Swann's Way and then that of the narrator and Gilberte here so similar that I very briefly toyed with the idea that Swann and the narrator are actually the same person! The next section "Place-Names: The Place" was a lot of fun and much more interesting to me, as new characters greatly opened up the narrative, and probably the narrator's world as well.

The end of this section contains a detailed description of a painting by the fictional artist Elstir that's quite beautiful. I loved the last section "Seascape, with Frieze of Girls" ; it evoked for me the feelings I think many have when they first become romantically interested in others. I was reminded of being at a Mardi Gras parade when I was about 12 or 13 when a boy in an out-of-town marching band took a pair of beads from around his neck and threw them to me after our eyes had caught: I think most everyone has, or will have, a story like that that sticks with them down through the years.

As Proust points out, it's not always the person per se that you're attracted to, having more to do with the time he or she comes across your vision. Near the end of the book, the tone changes in almost a chilling way, and the very last image is startling. Marcel Proust is a writer I completely miss the point of. I have no interest in society, especially this dead French one.

I can't seem to interest myself in these children's parties or these petite bourgeois parents scheming to meet this or that VIP government minister. My God, the tedium! Yet Tolstoy and Bellow and Ozick and scores of others have all written about particular dead cultures which I've enjoyed reading about immensely. I can't put my finger on it with Proust. His inability to invol Marcel Proust is a writer I completely miss the point of. His inability to involve me remains a mystery. Well, I shall stop trying to read him and cut my losses for good.

View all 22 comments. Jan 08, Madeleine rated it really liked it Shelves: Is there any period of time more frustrating, conflicting and downright disappointing than that too-long span of gawky limbs and endless opportunities for embarrassment? When one's body is alien territory, when one is faced with an onslaught of wholly unfamiliar impulses, when the head and the heart and all of the hormones are battling for control over a vessel that just wants things to make the kind of black-and-white sense they did in the blissfully naive days that are just ou Oh, adolescence.

When one's body is alien territory, when one is faced with an onslaught of wholly unfamiliar impulses, when the head and the heart and all of the hormones are battling for control over a vessel that just wants things to make the kind of black-and-white sense they did in the blissfully naive days that are just out of arm's reach but already rapidly fading memories, constantly pushed farther and farther away by the systematic remapping of a formerly recognizable world. Both Proust's narrator -- still imbued with vestiges of an innocence that can only take root in a childhood shaped by terminal sensitivity -- and his vulnerable heart stumble cautiously and cluelessly beyond youth's idyllic safety zone into the uncharted realm of life after puberty: He is, indeed, alone in the umbra cast by blossoming young girls who have gained his affections but will not share the warmth of their vernal lights with him.

One of Proust's most obvious successes with this volume is the familiar poignancy he gives to the fumbling initial efforts of gaining another young heart's favor because, really, did any of us understand the objects of our blindly obsessive desires at that age? Reading this book was like going through all those terrible milestones all over again, only with each misstep beautifully rendered and every confused failure examined with an enviably erudite melancholy that still captures the fatalistic immediacy of all those awful lessons' first cuts.

From the beginning, his understanding that the world he had not long ago regarded with a child's certainty was now turned on its head was apparent, as the feverishly anticipated chance to see his favorite actress results in the kind of shattering disappointment specially reserved for those times when an impossibly idealized dream becomes a vapid reality.

This is only the first in a series of crushing blows, though: The narrator's dreams of literary greatness are effectively dismantled by his father's colleague; a beloved writer has little in common with the literary persona he has come to adore; his first taste of love sours with his beloved's cooling interest and cruel neglect; the church at Balbec simply does not live up to his expectations. But the necessary dethroning of old favorites and the tarnishing of long-upheld ideals make way for the man the narrator is to become, just as childhood's magic sooner or later drains from all those things that once so enthralled our younger selves.

It is imperative that the narrator grow tired of such things so he can make new discoveries: His happiness is no longer derived solely from the sensory delights of a delicious feast, the beauty of nature, his mother's love, the wonder of the arts -- though the echoes of these things do reach the core of his soul to move him with their familiar stirrings of joy when they prove to be at their most resplendent moments. With age comes discrimination: As one can no longer live in a constant state of marvel distracting him from the myriad things to be discovered both within and without him, he also must learn what is truly worth his awed regard.

Like all teenagers, the narrator gradually distances himself from his family, focusing on the friendships and infatuations that define life on the brink of adulthood.

Henneth Annun Reseach Center

And, like every teenager I ever knew, some of those friendships are based on convenience rather than a mutual affinity for each other's company. The deepening bond between the narrator and Robert serves as a beautiful foil for the narrator's desperate attempts to tally the redeeming qualities within Bloch, a back-home chum whose coarse manner and general inability to recognize his own countless flaws make his presence difficult to bear even at a reader's safe distance. The two dueling personalities embody the narrator's own wavering balance between youthful indiscretion and the discrimination of experience, highlighting the decay of the former as it becomes unreasonable to cling to such childishness to any longer.

Just as not every girl the narrator fancies will return his interest, he no longer has to subscribe to the youthful notion that he ought to be friends with everyone. Proust's writing is the real star of the show here, with a sumptuous language that just drips poetry from each page. His insights prove time and again that human nature is constant across the ages, even though people themselves are in constant states of adapting to both interior and exterior forces. What I found the most remarkable, though, was the way he takes the tired tradition of similes to positively novel heights by playing two almost diametrically opposing elements against each other to fully express the emotional resonance of a seemingly insignificant moment: A household cook's reverence for her cuisine is likened to Michelangelo's dedication to his art; the fading hope of restoring a broken relationship is akin to the panicked desperation of a wounded man who has drunk his last vial of morphine; "[j]ust as the priests with the broadest knowledge of the heart are those who can best forgive the sins they themselves never commit, so the genius with the broadest acquaintance with the mind can best understand ideas most foreign to those that fill his own works.

This is people-watching at its finest, a tour of humanity with an unusually tender soul leading the way through his own emergence into adulthood and his discovery of the world around him. View all 10 comments. I wrote a review. And, in truth, I ended up being a bit harsh and hyperbolic in that review; but I soon came to second-guess myself. Unconsciously, imperceptibly, my whole concept of the novel had changed.

So it feels a bit dishonest of me to say anything negative about Proust; maybe all my negative sentiments are just a psychological defense mechanism, meant to shield myself from feeling overwhelmed by the influence Proust has exerted over me. Still, even if we know we are deluding ourselves, we must, in the end, accept the delusions, for we have nothing to replace them with.

So here are mine. Perhaps you will think me odd, but I find love a very boring topic for art. Love is, after all, an emotion—a very fine and very beautiful emotion, of course, but an emotion just the same. To be fair, this book is far from a sappy love song. He anatomizes every instant; he conducts autopsies of every slight memory. But I must confess that even this bores me. Am I a philistine? But, really, why is this phenomenon so fascinating to so many?

The Shadow of a Great Rock: A Literary Appreciation of the King James Bible by Harold Bloom

I saw, sitting on the shelf, a little band of apples; and these apples, which lay there so innocently, so playfully, so indistinguishable from one another, at once absorbed my total attention. I saw them there, sitting in the harsh light of the supermarket, their waxy skin gleaming attractively; and this gleam of light awakened in my stomach rumblings and stirrings, which, as I reflected, must have existed there all along, dormant, waiting to be awakened by the sight of some fruit.

But as I reached out my hand, picking up the apple that most caught my fancy, my expectations were shattered; it felt so weightless in my hand, and its waxy skin felt so much like plastic, that my desire was immediately destroyed, my hunger abated, and I put back the apple—thrown back once more into that confusion of hunger, knowing that I wanted food, but not knowing what I wanted to eat.

And, in my heart, I suspect that I will, once again, come to reproach myself for being harsh and hyperbolic in a review of Proust. My complaints are the complaints of a whining child, annoyed at his mother opening the blinds, letting the bright sunlight come streaming in.

After all, it takes a long time for your eyes to adjust. What Proust was, and what In Search of Lost Time , when given the proper air and light, the proper attention, can instruct others to be, is an astute pupil of life. He was perhaps the most exacting and astute observer in modern literature, and his dedicated readers are, in essence, forced also to become as aware, as exacting, in their own perceptions, not only as they wade the ebb and flow of his tide of words, but beyond that, when the book is closed and put away.

For as the sound of the ocean a What Proust was, and what In Search of Lost Time , when given the proper air and light, the proper attention, can instruct others to be, is an astute pupil of life.

Shadow of The Fox

For as the sound of the ocean and the feeling of salt water and sun on skin lingers long into the night after one has been swimming all day I am stealing images from Balbec , a patina forms on the surface of one's perceptions, when one has been so much immersed in and worked on by this immense novel, that lingers well after one's attentions are necessarily drawn back to life. And that is the magic of Proust. He dissembles and examines each experience, not so much like a scientist or a surgeon, but like one attempting to reduce a painting to the individual brushstrokes that compose the image, and more than that, he presents alternate colors, contradictory images, questions himself and the object of his observation, isolates and scrutinizes layer after layer of sensory experience in the hope of revealing a truth, an intent, a raw emotion, a lost memory; and this process, within his work, is life.

The one is the unheard of, the unprecedented, the height of bliss; the other, the eternal repetition, the eternal restoration of the original, the first happiness. It is this elegiac idea of happiness- it could also be called Eleatic- which for Proust transforms existence into a preserve of memory. So it is when he first goes to see Berma in Phaedra , or when he first meets his adored novelist Bergotte, or the entirety of his love for Gilberte, or his first visit to the Balbec cathedral so lengthily imagined in Swann's Way , or his first night in the beach town, or his first actual conversations with Albertine.

Such might be expected with an imagination as active and vast as Marcel's, but it is also a technique of Proust the artist, another way of digging into the unique and individual nature of human thought; one confronts the reality behind his perceptions of the world, one is deceived, one must compensate, one seeks another truth in the wreckage of dashed expectations.

After all these "firsts" that so often confound Marcel, a second, or a tertiary reality is formed from his "eternal restoration of the original"; it is from this churning and reworking of sensation and consciousness that Proust develops his suppositions and discovers his happiness. Within A Budding Grove or In The Shadow of Young Girls in Flower , whichever title you prefer the latter is a literal translation, the former a completely adequate descriptor , follows Marcel into his adolescence, and finds his thoughts more concerned with relationships, love, and one's place in society.

He also begins to experience firsthand the world of artists and artistic expression. This is a consequence of Marcel's developing consciousness and his choice to become a writer though in reality he mistrusts his own abilities and rarely ever sets pen to paper , and the new company he comes to know through Mme Swann's salon. Proust's satire of the aristocracy really begins to take shape and sharpens here, too; he derides the snobbery, hypocrisy, and dilettantism among the privileged classes in wonderful and lengthy dictations of banal salon conversations.

But there is a more than disinterested curiosity underlying all of this, and his affection for Mme Swann is genuine, as is his admiration of the aesthetics of her house, her clothing, her world, not to mention her daughter. However, it is through a burgeoning artist's eyes that these are all taken in and adored. Each object, as viewed by Marcel, contains something of himself, is associated with a human being or an idea or an emotion; nothing under his gaze is permitted the useless existence of a mere possession or a trophy of wealth as it is to the middling bourgeoisie that he scorns.

Or, more exactly, what he scorns is falseness, shallowness, stupidity attempting to mask itself in blind adherence to fleeting fashions, snobbery in position and wealth, a lack of understanding and pity for humanity. Marcel's love for Gilberte keeps him returning to these gatherings, but even that ends up more of a projection of his vivid longings and desires than any solid relationship. His last vision of Mme. Then Marcel travels with his Grandmother to Balbec the seaside resort city he so desired to visit at the end of Swann's Way , where he dreamt of witnessing the spectacle of thunderstorms over the ocean for a page summer.

Here his senses expand in relation to the span of the sea and the unexpected brightness and play of the sunlight, his anxieties and sicknesses are seemingly tempered by the fresh air and the new relations he acquires there, and he quickly forgets thunderstorms and unrequited feelings for Gilberte. Marcel's sensitivity to place and instance are peaked at the seashore, and there are endless brilliant descriptions of sea, sun, and landscape. Three examples of the sea as seen from his window: I returned to the window to have another look at that vast, dazzling, mountainous amphitheatre, and at the snowy crests of its emerald waves, here and there polished and translucent, which with a placid violence and leonine frown, to which the sun added a faceless smile, allowed their crumbling slopes to topple down at last.

At Balbec Marcel befriends Robert de Saint-Loup, an unselfconscious aristocrat who plays a larger role in the next volumes of the novel, M. Proust considered this volume of In Search of Lost Time to be a transitional piece, and it does do more setting up of expectations than presenting resolutions.

Shadows Bloom [T.A. Moore] on www.farmersmarketmusic.com *FREE* shipping Shadows Bloom is a stand-alone novel in T.A. Moore's Tales of the Even. Read more Read . Between the real and the unreal, the created and uncreated lies the capstone of the universe: the living city, Even Na Shetiyah. Eternally in flux and the only door .

But the brilliance of this book is in the minutiae of observation, the delicate, painterly prose that gives each thing life and particularity, the continual renewal and surprise of perception that is the ever present magic in Proust's art. And especially during his summer at Balbec, Proust allows Marcel to possess moments of that rare substance, happiness, the desperate seeking of which could be said to be the impetus for the whole composition of In Search of Lost Time: We ate our food, and if I had brought with me also some little keepsake which might appeal to one or other of my friends, joy sprang with such sudden violence into their translucent faces, flushed in an instant, that their lips had not the strength to hold it in, and, to allow it to escape, parted in a burst of laughter.

They were gathered close round me, and between their faces, which were not far apart, the air that separated them traced azure pathways such as might have been cut by a gardener wishing to create a little space so as to be able himself to move freely through a thicket of roses.

In Part 2, while on vacation to the fictional? I do tend to read his writing a lot slower than my usual speed because I enjoy the language, the imagery and the soothing nature of his descriptions. I enjoyed his introspective musings on love and the process of falling in and out of love. Proust gives us a lot to think about, for example in the following quote: A character, the Marquis de Norpois, quotes a fine Arab proverb- The dogs may bark; the caravan goes on.

And so the ISoLT saga continues— Marcel has a meandering tale to tell and he will take his fine time telling that—fall in line or else, vamoose! A lot happens in the second book— new characters, new themes are introduced.

Get A Copy

In Swann's Way, Bloch opened up a new world to Marcel by introducing him to Bergotte's work, now he initiates the latter into mysteries of flesh. There's this amusing comment by Gass in The Tunnel: O sure, we know why Proust wrote: And that, as we also know, requires an endless book. One day, a man who just now is very much in the eye, as Balzac would say, of the Faubourg Saint-Germain, but who at a rather awkward period of his early life displayed odd tastes, asked my uncle to let him come to this place.

My uncle pretended not to understand, made an excuse to send for his two friends; they appeared on the scene, seized the offender, stripped him, thrashed him till he bled, and then with twenty degrees of frost outside kicked him into the street where he was found more dead than alive; so much so that the police started an inquiry which the poor devil had the greatest difficulty in getting them to abandon. The irony is that view spoiler [ this uncle, M. And friendship is a dispensation from this duty, an abdication of self. Even conversation, which is the mode of expression of friendship, is a superficial digression which gives us no new acquisition.

We may talk for a lifetime without doing more than indefinitely repeat the vacuity of a minute, whereas the march of thought in the solitary travail of artistic creation proceeds downwards, into the depths, in the only direction that is not closed to us, along which we are free to advance — though with more effort, it is true — towards a goal of truth. In its myth-making, the final pages take the book to a different stratosphere: And yet to myself the sound of my own voice was pleasant, as were the most imperceptible, the most internal movements of my body.

And so I endeavoured to prolong it. I allowed each of my inflexions to hang lazily upon its word, I felt each glance from my eyes arrive just at the spot to which it was directed and stay there beyond the normal period. A vida torna a ter os seus encantos: View all 4 comments. Upon checking into a hotel in Venice in the summer of , the man behind the reception desk raised his eyes in surprise when he saw the length of our stay. We rarely see people stay for more than a couple of nights.

Most only stay for one. On our first day we visited the famous spots, took great pictures, drank some delicious wine while watching tourists feed the pigeons in the Piazza.

- The Chihuahua: A New or Potential Owners General Care and Information Guide

- Financial Report - Next Plc: Feasibility Study of a new investment in Australia

- Guns on the Early Frontiers: From Colonial Times to the Years of the Western Fur Trade (Dover Military History, Weapons, Armor)

- Perfectly Ridiculous (My Perfectly Misunderstood Life Book #3): A Universally Misunderstood Novel

- Achieving an AIDS Transition: Preventing Infections to Sustain Treatment