The Richmond Campaign of 1862: The Peninsula and the Seven Days (Military Campaigns of the Civil War)

Contents:

Lists with This Book. This book is not yet featured on Listopia. The series approaches Civil War history a bit differently. Gallagher, as editor, complies essays from leading Civil War historians on issues connected to each book's subject. This approach is interesting, but also a weakness of the series and this book in particular. Some of the essays are thought-pro The Richmond Campaign of Some of the essays are thought-provoking and contain new or creative assessments of the people and events of in eastern Virginia.

Other essays are dull and uninformative. I endorse William Miller's piece on the Army of the Potomac's engineers and their herculean efforts on the Chickahominy as well as R. Krick's essay on Whiting's Division at Gaines's Mill. Gallagher's The Richmond Campaign of The Peninsula and the Seven Days is best suited to those readers without a deep grounding in Civil War history. For others, it is Three Star material. Jul 21, Bobsie67 rated it really liked it Shelves: This book goes beyond the battle, exploring the ructions of citizens North and South about the War, the role that race played during , and some of the reasoning behind the political strategies and military operations north and south.

Very enjoyable for those wanting to get a bit into the weeds on this battle. Apr 30, Josh Liller rated it really liked it Shelves: Rather than present another chronological history of the Peninsular Campaign and the Seven Days Battles, this book is a collection of essays by different historians each focusing on different aspects of the campaign and battles.

Mar 17, Kat rated it liked it. A bit hard to follow chronologically.

Civil War History

Jul 25, Joel Manuel rated it really liked it. A good selection of essays on the Seven Days, edited by Gary Gallagher. Rich rated it really liked it May 23, Jerry rated it it was amazing May 21, Andrew rated it liked it Jan 27, Justin rated it it was amazing Jul 29, Should one desire a soup-to-nuts narrative of the entire Campaign,perhaps the best book to recommend is Stephen Sears "To the Gates of Richmond". However, that statement is not intended as a slight to Mr. As stated earlier in this review, "The Richmond Campaign of " is very useful for a student of the Peninsula Campaign to use as an adjunct source for some additional and more in-depth information.

The information in Gallagher's book compliments very well the information gained from Sear's book. Book arrived on time with a nice tight binding and no underlining looks good. One person found this helpful. I agree with an earlier reviewer who writes that this book is a great companion or follow-up book to Stephen Sears "To the Gates of Richmond". Sears books gives a vivid account of the overall campaign, while this book offers some insightful essays about certain aspects of the campaign.

The authors are all experts in the field, and offer well written essays for the reader to contemplate. I really enjoyed this book because the authors cover a wide range of topics to include General McClellan's flawed performance, "Stonewall" Jackson's less than stellar leadership during the campaign, the artillery battle at Malvern Hill, "Prince" John Magruder's struggles, and the affect of the campaign on both Northern and Southern society.

These detailed essays offer readers the latest and greatest scholarship about the Richmond campaign.

- Drugs 2.0: The Web Revolution Thats Changing How the World Gets High?

- The Richmond campaign of 1862 : the Peninsula and the Seven Days.

- The Richmond Campaign of 1862: The Peninsula and the Seven Days.

- Practical Approach to the Management and Treatment of Venous Disorders!

They really helped me gain a much deeper understanding about what the campaign was like, why it was so important to the overall war effort for both sides , and most importantly, how did if affect those involved. I highly recommend this book for those "students" of the Civil War like me who are looking to gain a richer grasp of the events that happened during the Richmond campaign. If you have not read anything about the Richmond campaign usually referred to as the Pennisula and Seven Days campaign then I suggest that you read "To the Gates of Richmond" by Stephen Sear first, then this book.

See all 5 reviews. Amazon Giveaway allows you to run promotional giveaways in order to create buzz, reward your audience, and attract new followers and customers. Learn more about Amazon Giveaway. Set up a giveaway. Customers who viewed this item also viewed. Cold Harbor to the Crater: The Second Day at Gettysburg: Essays on Confederate and Union Leadership.

There's a problem loading this menu right now. Learn more about Amazon Prime. Get fast, free shipping with Amazon Prime. Get to Know Us. English Choose a language for shopping. Explore the Home Gift Guide. Amazon Music Stream millions of songs. Amazon Advertising Find, attract, and engage customers. Amazon Drive Cloud storage from Amazon. Alexa Actionable Analytics for the Web. AmazonGlobal Ship Orders Internationally. Amazon Inspire Digital Educational Resources. Amazon Rapids Fun stories for kids on the go.

Amazon Restaurants Food delivery from local restaurants. Union troops moved back into the woods after the Confederates left, but made no further attempt to advance. Although the action was tactically inconclusive, Franklin missed an opportunity to intercept the Confederate retreat from Williamsburg, allowing it to pass unmolested. Stanton and Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase on the Treasury Department's revenue cutter Miami.

Lincoln believed that the city of Norfolk was vulnerable and that control of the James was possible, but McClellan was too busy at the front to meet with the president. Exercising his direct powers as commander in chief, Lincoln ordered naval bombardments of Confederate batteries in the area on May 8 and set off in a small boat with his two Cabinet secretaries to conduct a personal reconnaissance on shore. Troops under the command of Maj. Wool , the elderly commander of Fort Monroe, occupied Norfolk on May 10, encountering little resistance.

After the Confederate garrison at Norfolk was evacuated, Commodore Josiah Tattnall knew that CSS Virginia had no home port and he could not navigate her deep draft through the shallow stretches of the James River toward Richmond, so she was scuttled on May 11 off Craney Island to prevent her capture. The Confederate defenders, including marines, sailors, and soldiers, were supervised by Navy Cmdr. Drewry, the owner of the property that bore his name. An underwater obstruction of sunken steamers, pilings, debris, and other vessels connected by chains was placed just below the bluff, making it difficult for vessels to maneuver in the narrow river.

On May 15, a detachment of the U. The battle lasted over three hours and during that time, Galena remained almost stationary and took 45 hits. Her crew reported casualties of 14 dead or mortally wounded and 10 injured. Monitor was also a frequent target, but her heavier armor withstood the blows. Contrary to some reports, the Monitor , despite its squat turret, did not have difficulty bringing its guns to bear and fired steadily against the fort. The two wooden gunboats remained safely out of range of the big guns, but the captain of the USS Port Royal was wounded by a sharpshooter.

Johnston withdrew his 60, men into the Richmond defenses. Their defensive line began at the James River at Drewry's Bluff and extended counterclockwise so that his center and left were behind the Chickahominy River , a natural barrier in the spring when it turned the broad plains to the east of Richmond into swamps. Johnston's men burned most of the bridges over the Chickahominy and settled into strong defensive positions north and east of the city.

McClellan positioned his ,man army to focus on the northeast sector, for two reasons.

First, the Pamunkey River , which ran roughly parallel to the Chickahominy, offered a line of communication that could enable McClellan to get around Johnston's left flank. Second, McClellan anticipated the arrival of McDowell's I Corps, scheduled to march south from Fredericksburg to reinforce his army, and thus needed to protect their avenue of approach.

White House, the plantation of W.

- Account Options.

- Peninsula Campaign!

- .

Lee , became McClellan's base of operations. He moved slowly and deliberately, reacting to faulty intelligence that led him to believe the Confederates outnumbered him significantly. By the end of May, the army had built bridges across the Chickahominy and was facing Richmond, straddling the river, with one third of the Army south of the river, two thirds north. This disposition, which made it difficult for one part of the army to reinforce the other quickly, would prove to be a significant problem in the upcoming Battle of Seven Pines.

On May 18, McClellan reorganized the Army of the Potomac in the field and promoted two major generals to corps command: Franklin to the VI Corps. The army had , men in position northeast of the city, outnumbering Johnston's 60,, but faulty intelligence from the detective Allan Pinkerton on McClellan's staff caused the general to believe that he was outnumbered two to one.

Numerous skirmishes between the lines of the armies occurred from May 23 to May Tensions were high in the city, particularly following the earlier sounds of the naval gun battle at Drewry's Bluff. While skirmishing occurred all along the line between the armies, McClellan heard a rumor that a Confederate force of 17, was moving to Hanover Court House, north of Mechanicsville. If this were true, it would threaten the army's right flank and complicate the arrival of McDowell's reinforcements. A Union cavalry reconnaissance adjusted the estimate of the enemy strength to be 6,, but it was still cause for concern.

Customers who bought this item also bought

McClellan ordered Porter and his V Corps to deal with the threat. Porter departed on his mission at 4 a. Morell , the 3rd Brigade of Brig. George Sykes 's 2nd Division, under Col.

- Murder on the California Zephyr: A Herlong Novel;

- Navigation menu;

- Adam! Where Are You?: Why Most Black Men Dont Go to Church.

- Get A Copy.

- The Richmond campaign of : the Peninsula and the Seven Days (eBook, ) [www.farmersmarketmusic.com]!

- Barddas: A Collection of Original Documents, Illustrative of the Theology Wisdom, and Usages of the Bardo-Druidic Systems of the Isle of Britain!

- Frequently bought together!

Warren , and a composite brigade of cavalry and artillery led by Brig. Emory , altogether about 12, men. The Confederate force, which actually numbered about 4, men, was led by Col. They had departed from Gordonsville to guard the Virginia Central Railroad , taking up position at Peake's Crossing, 4 miles 6. Porter's men approached Peake's Crossing in a driving rain. At about noon on May 27, his lead element skirmished briskly with the Confederates until Porter's main body arrived, driving the outnumbered Confederates up the road in the direction of the courthouse.

Porter set out in pursuit with most of his force, leaving three regiments to guard the New Bridge and Hanover Court House Roads intersection. This movement exposed the rear of Porter's command to attack by the bulk of Branch's force, which Porter had mistakenly assumed was at Hanover Court House.

Branch also made a poor assumption—that Porter's force was significantly smaller than it turned out to be—and attacked. The initial assault was repulsed, but Martindale's force was eventually almost destroyed by the heavy fire. Porter quickly dispatched the two regiments back to the Kinney Farm. The Confederate line broke under the weight of thousands of new troops and they retreated back through Peake's Crossing to Ashland. The estimates of Union casualties at Hanover Court House vary, from 62 killed, wounded, 70 captured to The Confederates left dead on the field and were captured by Porter's cavalry.

McClellan claimed that Hanover Court House was yet another "glorious victory over superior numbers" and judged that it was "one of the handsomest things of the war. The right flank of the Union army remained secure, although technically the Confederates at Peake's Crossing had not intended to threaten it. A greater impact than the actual casualties, according to Stephen W. Sears , was the effect on McClellan's preparedness for the next major battle, at Seven Pines and Fair Oaks four days later. During the absence of Porter, McClellan was reluctant to move more of his troops south of the Chickahominy, making his left flank a more attractive target for Johnston.

He was also confined to bed, ill with a flare-up of his chronic malaria. Johnston knew that he could not survive a massive siege of Richmond and decided to attack McClellan. His original plan was to attack the Union right flank, north of the Chickahominy River, before McDowell's corps, marching south from Fredericksburg, could arrive. However, on May 27, Johnston learned that McDowell's corps had been diverted to the Shenandoah Valley and would not be reinforcing the Army of the Potomac.

He decided against attacking across his own natural defense line, the Chickahominy, and planned to capitalize on the Union army's straddle of the river by attacking the two corps south of the river, leaving them isolated from the other three corps north of the river. If executed correctly, Johnston would engage two thirds of his army 22 of its 29 infantry brigades, about 51, men against the 33, men in the III and IV Corps.

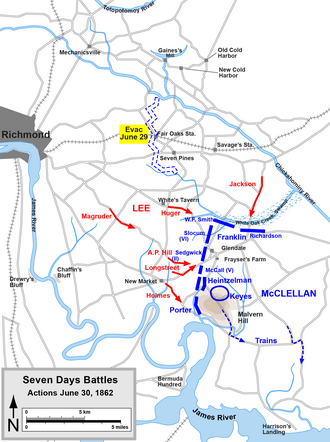

The Confederate attack plan was complex, calling for the divisions of A. Hill and Magruder to engage lightly and distract the Union forces north of the river, while Longstreet, commanding the main attack south of the river, was to converge on Keyes from three directions. The plan had an excellent potential for initial success because the division of the IV Corps farthest forward, manning the earthworks a mile west of Seven Pines, was that of Brig.

Silas Casey , 6, men who were the least experienced in Keyes's corps. If Keyes could be defeated, the III Corps, to the east, could then be pinned against the Chickahominy and overwhelmed. The complex plan was mismanaged from the start. Johnston issued orders that were vague and contradictory and failed to inform all of his subordinates about the chain of command. On Longstreet's part, he either misunderstood his orders or chose to modify them without informing Johnston, changing his route of march to collide with Hill's, which not only delayed the advance, but limited the attack to a narrow front with only a fraction of its total force.

Follow the Author

Exacerbating the problems on both sides was a severe thunderstorm on the night of May 30, which flooded the river, destroyed most of the Union bridges, and turned the roads into morasses of mud. Huger's orders had not specified a time that the attack was scheduled to start and he was not awakened until he heard a division marching nearby. Johnston and his second-in-command, Smith, unaware of Longstreet's location or Huger's delay, waited at their headquarters for word of the start of the battle.

Five hours after the scheduled start, at 1 p. Hill became impatient and sent his brigades forward against Casey's division. Casey's line buckled with some men retreating, but fought fiercely for possession of their earthworks, resulting in heavy casualties on both sides. The Confederates only engaged four brigades of the thirteen on their right flank that day, so they did not hit with the power that they could have concentrated on this weak point in the Union line. Casey sent for reinforcements but Keyes was slow in responding.

Eventually the mass of Confederates broke through, seized a Union redoubt, and Casey's men retreated to the second line of defensive works at Seven Pines. Hill, now strengthened by reinforcements from Longstreet, hit the secondary Union line near Seven Pines around 4: Hill organized a flanking maneuver to attack Keyes's right flank, which collapsed the Federal line back to the Williamsburg Road.

Johnston went forward on the Nine Mile Road with three brigades of Whiting's division and encountered stiff resistance near Fair Oaks Station, the right flank of Keyes's line. Soon heavy Union reinforcements arrived. Sumner, II Corps commander, heard the sounds of battle from his position north of the river.

On his own initiative, he dispatched a division under Brig.

Tanner rated it liked it Feb 07, Would you also like to submit a review for this item? This page was last edited on 13 November , at Write a review Rate this item: John Newton 's brigade in the woods on either side of the landing road, supported in the rear by portions of two more brigades Brig.

John Sedgwick over the sole remaining bridge. The treacherous "Grapevine Bridge" was near collapse on the swollen river, but the weight of the crossing troops helped to hold it steady against the rushing water. After the last man had crossed safely, the bridge collapsed and was swept away.

Table of Contents: The Richmond campaign of :

Sedgwick's men provided the key to resisting Whiting's attack. At dusk, Johnston was wounded and evacuated to Richmond. Smith assumed temporary command of the army. Smith, plagued with ill health, was indecisive about the next steps for the battle and made a bad impression on President Davis and General Lee, Davis's military adviser.

After the end of fighting the following day, Davis replaced Smith with Lee as commander of the Army of Northern Virginia.