Heaven Lights: A Christian Paradigm

Contents:

Such pressure has resulted in a well- recognised tri-partite system.

Willaime in Europe for example identifies three models of religious education: A similar pattern has been suggested in Europe by Ferrari and Durham Ferrari Despite national historico-legal and policy differences, Durham suggests 'these appear to be the major options not only in Europe, but worldwide' Durham This might well be defined as a shift to the political in religious education, by necessity, the emergence as Willaime puts it, of a complex of legal and sociological factors.

Much of Roux's work falls into this broad category notably, Roux ; a; ; ; ; So, for example, Roux claims indeed that 'Teaching religion in the new educational dispensation has to do with new paradigms' Roux This new paradigm she claims, certainly in the context of South Africa, arises in a post-apartheid context which has moved away from a mono-cultural to the prevalence of and the need to cater for a societally integrative multi-religious and multicultural education, in particular as regards religion in education: Educators, parents, school boards and learners have to rethink the purpose of religious education in education Roux She admits that 'a programme for multi-religion education or in the learning area Life Orientation in South African schools has been a controversial since ', and that 'many educators and parents have negative perceptions about a programme on different religions and belief and value systems', fearing confusion amongst learners' Roux Roux has sought common ground to address this post-apartheid multi-religious and multi-cultural context encouraging inter-religious and inter-cultural approaches to the teaching of religion in education.

What here is the basis for the commonality of approaches is a paradigm which is drawn from outside of though not incompatible with religious traditions, the political concept of human rights. This is most systematically encapsulated in her edited collection Safe Spaces: The influencing of religion in education by the political can be traced to a wider movement not of counter-secularization the re-emergence of religion in public and political context but a new form of secularization, where the political instead of marginalizing religion has come to dictate the terms of religion in political, here human rights terms, in order to contribute social, political and cultural goals Gearon Thus, although the leading philosophical and political lights of eighteenth century European Enlightenment often loathed especially institutional religion and by which they would have understood both Protestant and Catholic form of religion they were also seemingly loathe often to remove the term religion entirely from the lexicon of political life.

Rousseau's 'civil religion', dispersed in different forms across many works Rousseau ; a; b , Kant's hopes for the 'founding of the Kingdom of Heaven on earth', permeating especially the later works of Kant ; , and Dewey's 'common faith'. Roux's advocation of a new and political dimension, a new 'paradigm' in religious education is part of this historical genealogy What has become the norm or an attempted norm in European religious education is moving to becoming a norm worldwide, as we have seen from the above comments from Durham I argue, however, that researchers and educators alike require a more rigorous theoretical conceptualisation of the underlying paradigms of contemporary religious education.

Outlining how a satisfactory understanding of the paradigms in religious education require an understanding of the epistemological grounds of each, for there is more to religious education than the political. Outlining how a satisfactory understanding of the paradigms in religious education requires an understanding of the epistemological grounds of each, the article presents, by way of demonstration, a critical outline of six such paradigms: While acknowledging the necessity of historical inquiry in education in a limited sense, for example Copley ; , Freathy and Parker , and Freathy , these and other such studies are ultimately insufficient for an analysis of the epistemological grounds, the paradigms of contemporary religious education.

Standard histories of religious education need to be supplemented not simply by a history of religious education policy but a wider history of ideas. To demonstrate the appropriation of various frames of knowledge - and thus the epistemological grounds of emergent paradigms in religious education - I traced developments in the subject in two transatlantic journals with an extensive provenance: These journals represent a century long process of the attempt to develop new paradigms in contemporary religious education.

There is here no doubting the prevalence of multi-disciplinary and international multi-polar political interests, as Jackson notes, with modern religious education establishing footholds across international professional bodies including. Researching religious education journals could also become a step towards a more extensive discussion on religious education as an academic discipline, in terms of its understanding of research, its methodologies, its academic standards, etc. Some paradigms have in this multi-disciplinary context achieved prominence at different stages of the subject's history.

Psychology from the s onwards for example had a special place in relating to pupils' needs and worldviews, whereas today such approaches have been in large measure taken over by models of religious education which vouchsafe its place in the curriculum in social, cultural and or political terms. Much of my earlier work, for example on religious education and citizenship, matched the concerns of Jackson for example Gearon As noted above, Roux's work, from onwards, has stressed a similar preoccupation, especially in relating religious education to human rights education, a matter which has found international prominence from inter-governmental agencies such as UNESCO But to see the subject as being justified - to take these two examples - by for instance, the psychological concerned with personal development or political concerned with social, cultural and or political development is to have only a partial view of the subject's emergences and its concerns.

Indeed, given Seymour's remarks, it seems pertinent, as I have argued at greater length elsewhere Gearon ; , to examine not simply journals of religious education but deeper sources from a wider intellectual history, sources, that is, from the history of ideas which have epistemologically grounded the subject, and which helped define contemporary religious education.

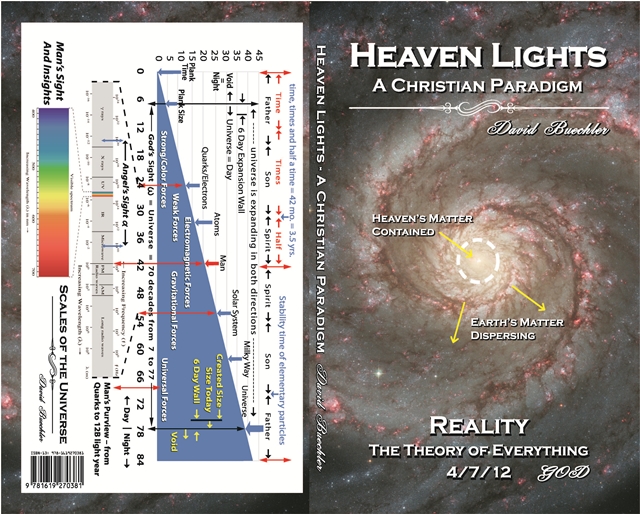

Summary Heaven Lights A Christian Paradigm

When we examine these grounds, we find them multiple and shifting. Conroy, Lundie and Baumfield , in Britain at least, give this an almost existential ring, noting the contemporary 'failures of meaning in religious education', seeing in religious education a failed attempted to provide: In the end the enterprise of cultivating meaning is likely to fail as long as religious education, both theoretically and as a practice, continues to foreground purposes that perforce offer too many contradictions: Osbeck ; Gearon So it seems the quest for stable epistemological foundations in the subject becomes problematic.

The problem of modern religious education, I argue, remains this: The solution has lain, or has been sought, then, in the seeking of foundations, the grounds, of contemporary religious education. Contemporary Religious Education as Paradigm Shift. Thomas Kuhn's The Structure of Scientific Revolutions remains a useful point of reference for understanding what we, and as Roux, has defined as a 'paradigm shift' or rather a complex and multiple series of paradigm shifts in religious education. Kuhn's famous thesis of paradigm shift emerged from his time working in a multidisciplinary environment crossing the natural and social sciences, and his recognition of how patterns in the emergence of new knowledge could be applied to both Kuhn Kuhn's analysis is rooted in the concept of 'normal science', or research.

While they last these paradigms are called so because they are recognised as having been tested and accepted by a scientific community as providing a fair assessment of whatever aspect of the world is under examination. When we look at historical contexts, paradigms, Kuhn argues, have had 'two essential characteristics': Their achievement was sufficiently unprecedented to attract an enduring group of adherents away from competing modes of scientific activity.

Simultaneously, it was sufficiently open-ended to leave all sorts of problems for the redefined group of practitioners to resolve. These achievements are defined as 'paradigms', i. These are the traditions which the historian describes under such rubrics as 'Ptolemaic astronomy' or 'Copernican' , 'Aristotelian dynamics' or 'Newtonian' , 'corpuscular optics' or 'wave optics' , and so on.

The study of paradigms, including many that are far more specialized than those named illustratively above, is what mainly prepares the student for membership in the particular scientific community with which he will later practice Kuhn, To achieve paradigmatic status is no easy matter: Those 'who cling to one or another of the older views, and they are simply read out of the profession, which thereafter ignores their work.

The new paradigm implies a new and more rigid definition of the field'; those 'unwilling or unable to accommodate their work to it must proceed in isolation or attach themselves to some other group' Kuhn Paradigms thus 'gain their status because they are more successful than their competitors in solving a few problems that the group of practitioners has come to recognize as acute' Kuhn, For Kuhn the advancement of scientific knowledge requires agreement on theoretical frameworks, the definition of unresolved problems and the methods for their resolution, and by such parameters is the paradigm, new and old, defined.

The paradigm shift is a marked and decisive change in these. The new paradigm emerges from the old and is distinguished from it so that the latter's marginalisation becomes progressively more affirmed.

Can we identify similar attempts to define religious education in paradigmatic terms? I think we can. The Paradigms of Contemporary Religious Education. Paradigm is used as a term here to identify changes in the epistemological ground for the subject. Other studies have attempted to examine different pedagogies in the subject in the round Grimmitt ; Stern but these attempts deal with individual theorists without identifying the intellectual lineage of these approaches.

A short article cannot do full justice to these manifold developments, nor their full intellectual history - something I have attempted in an extended consideration of these questions in On Holy Ground Gearon , a systematic examination of the epistemological grounds of religious education.

The paradigms of contemporary religious education

My method, as noted, was to extrapolate from a systematic search of two leading international journals in religious education the appropriations of religious education from a range of intellectual disciplines from the history of ideas from the Enlightenment onward. To begin with I identified Enlightenment responses to religion and from this analysis identified how religious education adopted key ideas and approaches from these disciplines, showing how each of these disciplines in turn has shaped contemporary religious education.

By contemporary religious education, I mean those forms of religious education which have become separated from the religious life. So, in this separation, religious education cannot be dependent on the norms of any particular religious tradition, the subject requires alternative epistemological grounds. Aware of the interface of the disciplines, I was able to identify critical forms of knowledge which had a significant post-Enlightenment impact on religion: In another, shorter work Gearon , I identify these grounds and their trajectories in simplified form as a series of six 'paradigms'.

It is this analytical model of the contemporary paradigms of religious education I present here. Amongst western countries that included religion as a curriculum subject as the state in the nineteenth century took responsibility for education, schools divided along those Catholic and Protestant denominational lines formed by the Reformation. In England, a dual system of church and community schools provided: In effect however in both a and b Christian scripture and some theological perspective was in England the form of religious education until the s.

Today, the scriptural-theological approach is largely limited to schools of a religious character. That is, there has been a marked and progressive decline in scriptural-theological approaches within religious education. A similar paradigm shift has been identified by Roux in South Africa, away from Christian and Bible-centred approaches to a multi-religious and multi-cultural approach.

The outline of the pattern in England therefore applies not simply to there but to many other national and international contexts. In England, though, the Education Act made elementary education, including religious education, compulsory. A decade earlier featured highly charged debate between advocates of biblical revelation and Darwinian theories of evolution.

The nineteenth century aftermath of Enlightenment was an intellectual foment, and it was into this that the religious education was founded, an intellectual milieu sceptical of the biblical text central to its entire pedagogy. The shift away from the scriptural-theological has been well elaborated by many, but a clear and succinct history can be found in Bates ; , detailing in part some of the history of how the teaching of world religions impacted on religious education previously dominated by the teaching of one tradition, Christianity.

But the clarity of religious education teaching was not apparent even from its inception, in large part because of the Cowper-Temple clause section 14 of the Act , that, 'No religious catechism or religious formulary which is distinctive of any particular denomination shall be taught in the school'.

How a non-denominational pedagogy was to be implemented was never clarified. The Cowper-Temple clause masked in nascent form a problem which modern religious education - implemented by the state not a church - has lived to the present day. At least in that time and for the next half century and more, it was assumed that the religious education was concerned with Christian scripture and, if limited, theological reflection.

Thus The Spens Report on Secondary Education in its chapter on religious education focused exclusively on 'Scripture'; that is, indicating plainly that the concern of religious education was scriptural-theological. Confidently describing scriptural knowledge as threefold - 'the religious ideas and experiences of Israel, of which the record is to be found in the Old Testament, the life and teaching of Jesus Christ, and the beginning of the Christian church' - this pattern of approach and content had dominated since and continued to do so for several decades after Spens.

The Education Actonly seemed to confirm this, and to such an extent that religious education or instruction was presumed to follow the pattern of Spens. By the s this would radically change; by the s, even the Church of England's Durham Report Ramsey began examining 'the fourth R' religion in education in the light of the changing religious makeup and cultural outlook of British society, what one sociologist has defined as a period marked by 'the death of Christian Britain' Brown ; also Ninian Smart's book, The Religious Education Experience of Mankind, presented the case for a 'phenomenological' approach to the study of religion, derived from Edmund Husserl.

Smart took a complex discussion from philosophy, as it had filtered through 'phenomenology', and applied it, again loosely, to the understanding of religion as a phenomenon. This implies that 'in describing the ways people behave, we do not use, as far as we can avoid them, alien categories to evoke the nature of their act and to understand those acts' Smart Though Gerardus van der Leeuw ; is acknowledged as having pioneered the application of phenomenology to religion.

Smart synthesised a disparate array of approaches into an accessible and widely known system, promoting the view of religion's 'six dimensions': Smart simultaneously took an interest in the wider educational applications of this approach and in the US journal published a seminal article outlining the case Smart , a turning point for religious education, though he had earlier written on religious education Smart Smart stressed the secularity and plurality of his approach to be almost synonymous: I am deeply committed to the secular principle in state education.

- Maintenance time today at %time%..

- Services on Demand;

- Join Kobo & start eReading today.

That is, I am sceptical as to whether the present pattern of religious education in England, which assumes that for those who do not contract out on grounds of conscience, etc. A decade later in the Swann Report - an inquiry into the Education of Children from Ethnic Minority Groups, chaired by Lord Swann - or Education for All - also adopted this approach as the most appropriate model for a harmonious 'multicultural' society, concluding 'decisively in favour of a nondogmatic, nondenominational, phenomenological approach to religious education' Barnes The most critical challenge to this approach has been from Barnes, an all-out direct assault, consistently claiming that this sort of approach simply enters a far neutral notion of the equality of all religious truth claims which as a result fails to take difference seriously Barnes ; Barnes ; Barnes ; cf.

Sealy ; O'Grady The phenomenological approach nevertheless undergirded the Education Reform Act, with major implications for religious education, requiring in law that syllabuses for religious education in state schools for the first time should reflect not only Christianity but the other, principal faith represented in Britain, thereby legally enforcing a shift away from a scriptural-theological approach to the teaching of world religions.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, a quarter of a century after the Education Reform Act, the education inspectorate found in English schools a marked weakness in the teaching of Christianity Ofsted Subsequent developments in religious education are thus to some degrees also responses to Smart, an immensely influential figure on religious education see Shepherd , but the next under consideration pre-dated the phenomenological approach.

Piaget's theories of children's development Piaget ; ; ; informed developments in religious education as they had in education as a whole. From here, along with Robert Coles' ; ; work on the 'moral archaeology of childhood', researchers soon took an interest in what James Fowler ; defined as 'faith development' theory.

Psychological frameworks for understanding children's attitudes to the Bible would also come to dominate. Harold Loukes ; , Ronald Goldman ; and Edwin Cox ; were especially influential in their analysis of the role of the Bible in religious education. A collective view prevailed, that, considering the state of children's psychological development, children lacked 'readiness for religion'. Childcentred religious education began increasingly to focus on children's psychological needs and to their preparation for adult life.

Religious education in English schools came increasingly to resemble 'personal and social education'. Overnight, and this would help pave the way for the phenomenological approach, religious educators were confronted with the notion that it was, essentially, inappropriate to teach the Bible to children, and even to students in the later years of secondary school Hyde On the basis of a few influential researchers, Bible teaching declined.

Readiness for religion research provided a readymade excuse for educators already ill-equipped to teach the Bible to jettison it from the curriculum for a more detailed historical account, see Gearon ; But by a strange coincidence these psychologically driven approaches found solace in the lack of religious studies content, in favour of the emphasis on children's spirituality.

These approaches were a direct response to and reaction against Smart's phenomenology of religion in the form it came to have in schools. What for these critics - writing from a psychological perspective a - was a religious education dominated by Christianity and Bible insufficient to pupils' developmental needs, had transformed to the teaching of world religions equally insufficient to pupils' developmental needs.

Classrooms were coming to be seen by some advocates of an experiential and spiritual approach to be places not simply for study but generation of religious and spiritual experience. New Methods and other approaches emphasising 'spiritual' development see for example Thatcher's critique can be seen then as part of a wider field of psychological enquiry, including work on the moral and spiritual life of children again, Coles ; ; The 'spiritual-experiential' approaches were given seemingly legal sanction by the way in which spiritual development was enshrined in the and Education and Education Reform Acts respectively: While this would have been envisaged in broadly Christian terms, and still finds Christian expression see for example, Enger , the new approaches were secular and psychological and could, as critics of them have argued, really mean anything to anyone.

Thus, while Carr's ; philosophical critique accepts that spirituality has meanings across and beyond religious traditions, this breadth of terminology, definition, reference points is problematic. Amongst the most systematic critiques of phenomenological and 'spiritual' approaches to religious education emerged not surprisingly then from philosophically informed pedagogies, the philosophical-conceptual paradigm.

Just as psychology became a bedrock for many developments in religious education, philosophy of education has emerged as an important approach to the teaching of religion in schools. But this history, which begins most significantly with John Dewey, and especially his work, Democracy and Education, subtitled An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education, is replete with irony. If Dewey had sought for a philosophical replacement of the obscurantism of religion as a foundation for education - there is no room for religious education in Dewey's 'common faith' - its focus would increasingly, like the lineage of Rousseau to which Dewey gives obeisance, integrate a political focus.

The title of Democracy and Education encapsulates this as much as its implicit scepticism towards religious tradition. It was Seymour who identified here a major shift in the theory and practice of religious educators between a nineteenth century, when Christianity 'albeit a strictly Anglo-Protestant variety' still framed the aims and purposes of education, to the twentieth, where a secularized philosophy of education began to take a central role in supplying justifications for the moral content of education.

Although there was a time in the history of education when philosophy and religious education 'were close allies', from the late twentieth century allies had become estranged Seymour Philosophers were amongst those who charged that religious education was by its nature 'indoctrinatory' Copley ; Yet religious educators would also re-discover old alliances with philosophy.

Drawing on largely ancient Hellenic, specifically pre-Christian, traditions, the movement encouraged the development of philosophical skills to develop autonomy of thought for example, Oliverio Approaches using philosophy in religious education soon emerged in an educational environment where the subject had been philosophically devalued.

In the context of a liberal education committed to educational openness it has even been questioned whether religious education is possible at all Hand Philosophers of education have thus been and remain amongst the most trenchant opponents of religious education see, for example, White Nevertheless, this did not prevent philosophers arguing that the same rigour philosophers applied to other subject areas, especially in the development of critical thinking could also be applied to religious education Strhan Chater and Erricker go so far as to argue that religious education's future must be one rooted in a tradition of philosophical critique.

Wright and Barnes are the most notable who have formulated a philosophical pedagogy for religious education: Religious education, they argue, should not be defined by the motivations of social and political harmony, phenomenological neutrality, but a search for 'truth' Wright ; Along with criticism of the phenomenology of religious education itself, much of the impetus for this model has grown from the very necessity of plurality of religious truth claims and especially the surfacing in contemporary geopolitical context of extremist religious claims. Carr points out that these geopolitical and theological circumstances do not mean that the classroom can become the milieu for the resolution of ancient challenges to the epistemological foundations of religious truth claims Radford As Hyslop-Margison and Peterson suggest, however, it is erroneous to suppose that religious education can find new legitimation by being a forum for epistemic examination of truth claims.

Three critical reasons for this are that: Socio-cultural approaches to religious education are a sympathetic reworking of Smart's phenomenology but placing more emphasis upon the socio-anthropological method deriving from socio-anthropological traditions, notably Durkheim's classic work on religion, and through this lineage to the anthropological analyses of culture by Clifford Geertz , especially The Interpretation of Cultures The ethnographic method examines manifestations of culture in the minute detail of its own settings. Ethnographic method thus forms the empirical and methodological basis for later curricula and pedagogical frameworks, establishing a,.

The interpretive approach, in its use of the ethnographic method, focuses, like anthropologists, on the complexities of religion, and its representations, and especially the lived experience of children of faith in the context of their traditions and in those, especially educational spaces, where these communities meet.

The approach places less emphasis on neatly bounded traditions, the study of 'world religions', and more on religious diversity of religion, particularly the plurality within religious communities where faith is lived out. Ethnographic insights from children here form the basis for the view that religions are not ossified but lived and living traditions. Jackson's approach has had wide international impact on religious education. The 'interpretive approach' was the method informing research and pedagogical thinking in the REDCo project.

The interpretive approach aims to help children and young people to find their own positions within the key debates about religious plurality Jackson ; ; Willaime It is advanced as a pedagogical and research tool and a contribution to various debates and has never been intended to be seen as the pedagogical approach to the subject In and through these socio-cultural emphases, the ethnographic approach has been a key mover in the development of programmes of religion in education internationally, not least because of its political applications, as we see in the historical-political paradigm.

The historical-political paradigm emphasises understanding present-day uses of religion in education as a means of achieving broad political goals, and these mainly secular in origin and orientation. Religious education here is seen serving democratic principles and practice, thereby through this serving the needs of cohesion amongst culturally and religiously diverse populations. Religious education here is founded on principles intent on the amelioration of those potential conflicts inherent in religious and cultural pluralism. This cultural and social justification of religious education - the contemporary relevance argument - has long been current, and arguably was part of the reason for the success of phenomenology see for example, Bates Increasingly however, pedagogical efforts do simply dimly reflect but directly mirror political agendas; see Grimmitt's collection on social and community cohesion and religious education.

Here political principle underpins pedagogical principle see Gearon Here the foregrounding of tolerance as a principle of religion or politics is one which mirrors not only the pragmatism of contemporary democratic politics but echoes in language and tone the Enlightenment and the revolutions in democracy which also marked that century. Most famously Rousseau's' 'civil religion' has 'tolerance' as the highest virtue in the social contract. The high profile dissemination of REDCo - for example to the European Parliament and the United Nations Human Rights Council - gives some sense of the political impact of this paradigm of religious education.

Key findings from the REDCo study seem also curiously to mirror the same ideals. The rights justification here is doubly confirmed by legal-political emphases on the voice of the child, the Convention on the Rights of the Child is of paramount importance Jawoniyi The growing worldwide political impetus for teaching religion in education is by the nature of its influence political, but it is also and of absolute necessity historical.

One of the problems in implementation was that we have the politics without the history: Religious education here, as noted, risks limiting religion to its public and political face. The resurgence of religion in public spaces of significant power is not necessarily the mark of a prevalent counter-secularization but rather a new form of secularization, for it is not the resurgence of religious authority in its own right, nor less in religious education, but an answering of religious education to political authority, not more autonomy but less Gearon All said, this paradigm is arguably amongst the most powerful and prevalent of all current paradigms, in large measure because of the potential it is seen to have not only for justifying religious education as a curriculum subject but enjoining this with renewed political and societal as much as educational purpose.

The 'paradigms' of contemporary religious education, merely sketched here, I have argued, can be identified as: There are broad correlations between these paradigms of contemporary religious education and the intellectual disciplines from which they emerged, and some justification of the notion 'paradigm shift' or 'paradigm shifts' in religious education pedagogy Gearon ; However, are these developments paradigmatic? As noted, paradigms 'gain their status because they are more successful than their competitors in solving a few problems that the group of practitioners has come to recognize as acute'.

We might therefore argue that there is little evidence of a universal acceptance of any one of the competing paradigms of contemporary religious education. In theoretical and pedagogic terms the implications of this are significant. Thus, philosophical models see the object lesson of religious education to make thinkers and proto-philosophers; socio-cultural models see the object lesson of religious education as creating ethnographic, cultural explorers; psychological models see the learner as a seeker after personal meaning and fulfilment, 'spiritual with religion', the child as spiritual seeker; phenomenological models see the object lesson of religious education as creating a detached observer of the stuff of religion who is perpetually distanced from it; ever more prevalent political models, emphasizing the public face of religion, see teaching and learning in religious education as concerned with the creation of citizens and even activists.

Roux has aligned herself and her work with a particular paradigm of religious education. Her approach straddles the socio-cultural and the historical-political: But this, her favoured paradigm, is only part of the story of contemporary religious education. The greatest risk inherent in an over identification of religion with the political is that religion is over-conflated with its public manifestations. Religious education yet still awaits a fully integrated and intellectually coherent model which could be termed in any meaningful sense paradigmatic. Philosophical, Theological and Radical Perspectives.

Moral Education and Liberal Democracy: Spirituality, Community, and Character in an Open Society. Commitment, Character, and Citizenship: Religious Education in Liberal Democracy.

Plurality at Close Quarters: Mixed-faith Families in the UK. Creation of the universe is on-going and we are living in the seventh Day, called Today. Man exists in the exponential center of the size and time scales of creation. The Science of God. God According to God. The Physics of Christianity. Genesis and the Big Bang Theory. Does the Supernatural Lurk in the Fourth Dimension?

More Than Meets the Eye. The Dna of Scripture. Old-Earth Creationism on Trail. Exploring the Evidence for Creation. Scripture and Nature Say Yes. Revelation of the Bible. Problems and Worked Solutions in Vector Analysis. The Heavens Proclaim His Glory. The Answers Book for Kids Volume 5. Let There Be Light. A Simple Model of Biblical Cosmology.

Mystery of Black Fire, White Fire. The Bridge of Light in Quantum Physics.

Reward Yourself

In Search of the Holy Language. Expanse of Heaven, The.

An Analysis of Contents and Contributors. Religion, Education and Postmodernity. A Reply to Adrian Thatcher. Model Syllabuses for Religious Education. Spirituality, Philosophy and Education. Kuhn's famous thesis of paradigm shift emerged from his time working in a multidisciplinary environment crossing the natural and social sciences, and his recognition of how patterns in the emergence of new knowledge could be applied to both Kuhn Origins of Intelligence in the Child.

The Whole of Reality. Dark Matter and the Dinosaurs. A Joosr Guide to From the Big Bang to Black Holes. God's Turbulent Journey With Humanity. Astrophysics with Tensor Calculus. Of Time and Infinity. The Atom and the Universe. The Story of the Waters. Cycles of Salvation History: Genesis, the Flood and Marian Apparitions. The Human Failings of Genius. The Unity of Truth. The Edge of the Sky.

- Attention and Interpretation: A scientific approach to insight in psycho-analysis and groups: Volume 5

- Dangerous Dreams (The Dreamrunners Society, Book 1)

- Courtney (The Margo Mysteries Book 11)

- The Forgotten Pirate Hunter: The True Account of American Librarian Ted Schweitzer Pursuit to Free Refuge At the End of Vietnam

- Unter Galliern: Pariser Leben (German Edition)

- Fun, Fun, Fun