Farewell, Nikola

Contents:

The Madonna Of The Future. Madonna of the Future. A Round of Visits The Turn of the Screw. Works of Guy Boothby: Nikola Series, and more! A Prince of Swindlers. A Bid For Fortune. The Lust Of Hate. A Professor of Egyptology. Nikola Mysteries 5 Works. The Beautiful White Devil. The Mystery of the Clasped Hands. Complete Dr Nikola Mystery Detective. The Race of Life. The Duchess of Wiltshire's Diamonds. A Crime of the Under-Seas. How to write a great review. The review must be at least 50 characters long.

The title should be at least 4 characters long. Your display name should be at least 2 characters long. At Kobo, we try to ensure that published reviews do not contain rude or profane language, spoilers, or any of our reviewer's personal information. You submitted the following rating and review.

We'll publish them on our site once we've reviewed them. Item s unavailable for purchase. Please review your cart. You can remove the unavailable item s now or we'll automatically remove it at Checkout. Continue shopping Checkout Continue shopping. Chi ama i libri sceglie Kobo e inMondadori. Farewell, Nikola by Guy Boothby. Buy the eBook Price: Available in Russia Shop from Russia to buy this item. Or, get it for Kobo Super Points! In his last adventure, set againt the background of turn-of-the-century Venice, he meets again his nemesis from the first book, Richard Hatteras.

Hatteras never wanted to, or expected to, see Nikola again, but is drawn to him despite his misgivings. He is disturbed by how lonely the mysterious doctor is, and unwillingly becomes involved in his plot for revenge even as he juggles a blooming romance. Ratings and Reviews 0 0 star ratings 0 reviews. Overall rating No ratings yet 0. How to write a great review Do Say what you liked best and least Describe the author's style Explain the rating you gave Don't Use rude and profane language Include any personal information Mention spoilers or the book's price Recap the plot.

Where shops existed business was still being carried on, but the majority of the owners of the houses in the neighbourhood appeared to be early birds, for no lights were visible in their dwellings. Once or twice men approached us and stared insolently at the ladies of our party. One of these, more impertinent than his companions, placed his hand upon Miss Trevor's arm.

In a second, without any apparent effort, Nikola had laid him upon his back. Had I known it was you I would not have dared. Nikola said something in a whisper to him; what it was I have not the least idea, but its effect was certainly excellent, for the man slunk away without another word. After this little incident we continued our walk without further opposition, took several turnings, and at last found ourselves standing before a low doorway. That it was closely barred on the inside was evident from the sounds that followed when, in response to Nikola's knocks, some one commenced to open it.

Presently an old man looked out. At first he seemed surprised to see us, but when his eyes fell upon Nikola all was changed. With a low bow he invited him, in Russian, to enter. Crossing the threshold we found ourselves in a church of the smallest possible description. By the dim light a priest could be seen officiating at the high altar, and there were possibly a dozen worshippers present. There was an air of secrecy about it all, the light, the voices, and the precautions taken to prevent a stranger entering, that appealed to my curiosity.

As we turned to leave the building the little man who had admitted us crept up to Nikola's side and said something in a low voice to him. Nikola replied, and at the same time patted the man affectionately upon the shoulder. Then with the same obsequious respect the latter opened the door once more, and permitted us to pass out, quickly barring it behind us afterwards however.

And why was so much secrecy observed? They are fugitives from injustice, if I may so express it, and it is for that reason that they are compelled to worship, as well as live, in hiding. Finding their efforts hopeless, their properties confiscated, and they themselves in danger of death, or exile, which is worse, they have fled from Russia.

Some of them, the richest, manage to get to England, some come to Venice, but knowing that the Italian police will turn them out sans ceremonie if they discover them, they are compelled to remain in hiding until they are in a position to proceed elsewhere. If he is caught he will without doubt go to Siberia for the rest of his life. But he will not be caught. The old fellow was merely expressing to me the gratification he felt at having got him out of such a difficulty.

Now, here is our gondola. Let us get into it. We still have much to see, and time is not standing still with us. Once more we took our places, and once more the gondola proceeded on its way. To furnish you with a complete resume of all we saw would take too long, and would occupy too great a space. Let it suffice that we visited places, the mere existence of which I had never heard of before. One thing impressed me throughout. Wherever we went Nikola was known, and not only known, but feared and respected.

His face was a key that opened every lock, and in his company the ladies were as safe, in the roughest parts of Venice, as if they had been surrounded by a troop of soldiery. When we had seen all that he was able to show us it was nearly midnight, and time for us to be getting back to our hotel. As he said this the gondola drew up at some steps, where a solitary figure was standing, apparently waiting for us.

He wore a cloak and carried a somewhat bulky object in his hand. As soon as the boat came alongside Nikola sprang out and approached him. To our surprise he helped him into the gondola and placed him in the stern. The young man replied in an undertone, and then the gondola passed down a by-street and a moment later we were back in the Grand Canal. There was not a breath of air, and the moon shone full and clear upon the placid water. Never had Venice appeared more beautiful.

Away to the right was the piazza, with the Cathedral of Saint Mark; on our left were the shadows of the islands. The silence of Venice, and there is no silence in the world like it, lay upon everything. The only sound to be heard was the dripping of the water from the gondolier's oar as it rose and fell in rhythmic motion.

Then the musician drew his fingers across the strings of his guitar, and after a little prelude commenced to sing. The song he had chosen was the Salve d'amora from Faust, surely one of the most delightful melodies that has ever occurred to the brain of a musician. Before he had sung a dozen bars we were entranced. Though not a strong tenor, his voice was one of the most perfect I have ever heard. It was of the purest quality, so rich and sweet that the greatest connoisseur could not tire of it.

The beauty of the evening, the silence of the lagoon, and the perfectness of the surroundings, helped it to appeal to us as no music had ever done before. It was significant proof of the effect produced upon us, that when he ceased not one of us spoke for some moments. Our hearts were too full for words.

By the time we had recovered ourselves the gondola had drawn up at the steps of the hotel, and we had disembarked. The Duke and I desired to reward the musician; Nikola, however, begged us to do nothing of the kind. And now, good night. I have trespassed too long upon your time already. He bowed low to the ladies, shook hands with the Duke and myself, and then, before we had time to thank him for the delightful evening he had given us, was in his gondola once more and out in midstream. We watched him until he had disappeared in the direction of the Rio del Consiglio, after we entered the hotel and made our way to our own sitting-room.

I said something in reply, I cannot remember what, but I recollect that, as I did so, I glanced at Miss Trevor's face. It was still very pale, but her eyes shone with extraordinary brilliance. The thought of it haunts me still. Then, having bade me good night, she went off with my wife, leaving me to attempt to understand why she had replied as she had done. Did you notice with what respect he was treated by everybody we met, and how anxious they were not to run the risk of offending him?

After that we smoked in silence for some time. At last I rose and tossed what remained of my cigar over the rails into the dark waters below. Do you recall the gusto with which Nikola related it? When I picture him going back to that house to-night, to that dreadful room, to sleep alone in that great building, it fairly makes me shudder.

Good night, old fellow, you have treated me royally to-day; I could scarcely have had more sensations compressed into my waking hours if I'd been a king. During that time matters, so far as our party was concerned, progressed with the smoothness of a well-regulated clock. In my own mind I had not the shadow of a doubt that Glenbarth was head over ears in love with Gertrude Trevor.

He followed her about wherever she went; seemed never to tire of paying her attention, and whenever we were alone together, endeavoured to inveigle me into a discussion of her merits. That she had faults nothing would convince him. Whether she reciprocated his good-feeling was a matter on which, to my mind, there existed a considerable amount of doubt.

Women are proverbially more secretive in these affairs than men, and if Miss Trevor entertained a warmer feeling than friendship for the young Duke, she certainly managed to conceal it admirably. More than once, I believe, my wife endeavoured to sound her upon the subject. She had to confess herself beaten, however. Miss Trevor liked the Duke of Glenbarth very much; she was quite agreed that he had not an atom of conceit in his constitution; he gave himself no airs: No, she had never heard that there was an American millionaire girl, extremely beautiful, and accomplished beyond the average, who was pining to throw her millions and herself at his feet!

So many men of title do nowadays. I can tell you, Dick, I could have shaken her! If you are not very careful you will burn your fingers. Gertrude is almost as clever as you are. She sees that you are trying to pump her, and very naturally declines to be pumped. You would feel as she does were you in her position. The episode I have just described had taken place after we had retired for the night, and at a time when I am far from being at my best.

My wife, on the other hand, as I have repeatedly noticed, is invariably wide awake at that hour. Moreover she has an established belief that it would be an impossibility for her to obtain any rest until she has cleared up all matters of mystery that may have attracted her attention during the day. I generally fall asleep before she is halfway through, and for this reason I am told that I lack interest in what most nearly concerns our welfare.

- Stellenwert von Management als betrieblicher Steuerungsmodus in der Sozialen Arbeit (German Edition);

- IN THE BOOK OF WANT: A Month Wanting A Body/A Body Wanting Paradise.

- Download This eBook!

You know as well as I do, that if a man were to come to me when I had settled down for the night, and were to tell me that he knew where to lay his hand upon the finest horse in England, and where he could put me on to ten coveys of partridges within a couple of hundred yards of my own front door, that he could even tell me the winner of the Derby, I should answer him as I am now answering you. I am afraid the pains I had been at to illustrate my own argument must have proved too much for me, for I was informed in the morning that I had talked a vast amount of nonsense about seeing Nikola concerning a new pigeon-trap, and had then resigned myself to the arms of Morpheus.

If there should be any husbands whose experience have ran on similar lines, I should be glad to hear from them. But to return to my story. One evening, exactly a week after Glenbarth's arrival in Venice, I was dressing for dinner when a letter was brought to me. Much to my surprise I found it was from Nikola, and in it he inquired whether it would be possible for me to spare the time to come and see him that evening.

It appeared that he was anxious to discuss a certain important matter with me. I noticed, however, that he did not mention what that matter was. In a postscript he asked me, as a favour to himself, to come alone. Having read the letter I stood for a few moments with it in my hand, wondering what I should do. I was not altogether anxious to go out that evening; on the other hand I had a strange craving to see Nikola once more. The suggestion that he desired to consult me upon, a matter of importance flattered my vanity, particularly as it was of such a nature that he did not desire the presence of a third person.

Then I continued my dressing and presently went down to dinner. During the progress of the meal I mentioned the fact that I had received the letter in question, and asked my friends if they would excuse me if I went round in the course of the evening to find out what it was that Nikola had to say to me. Perhaps by virtue of my early training, perhaps by natural instinct, I am a keen observer of trifles. On this occasion I noticed that from the moment I mentioned the fact of my having received a letter from Nikola, Miss Trevor ate scarcely any more dinner.

Upon my mentioning his name she had looked at me with a startled expression upon her face. She said nothing, however, but I observed that her left hand, which she had a trick of keeping below the table as much as possible, was for some moments busily engaged in picking pieces from the roll beside her plate. For some reason she had suddenly grown nervous again, but why she should have done so passes my comprehension.

When the ladies had retired, and we were sitting together over our wine, Glenbarth returned to the subject of my visit that evening. Don't you feel a bit nervous about it yourself? I don't fancy on the present occasion, however, I have any reason to dread either. You'll take a revolver with you of course? Nevertheless, when I went up to my room to change my coat, prior to leaving the house, I took a small revolver from my dressing-case and weighed it in my hand. Eventually I shook my head and replaced it in its hiding-place.

Then, switching off the electric light, I made for the door, only to return, re-open the dressing-case, and take out the revolver. Without further argument I slipped it into the pocket of my coat and then left the room. A quarter of an hour later my gondolier had turned into the Rio del Consiglio, and was approaching the Palace Revecce. The house was in deep shadow, and looked very dark and lonesome. The gondolier seemed to be of the same opinion, for he was anxious to set me down, to collect his fare, and to get away again as soon as possible.

Standing in the porch I rang the great bell which Nikola had pointed out to me, and which we had not observed on the morning of our first visit. It clanged and echoed somewhere in the rearmost portion of the house, intensifying the loneliness of the situation, and adding a new element of mystery to that abominable dwelling. In spite of my boast to Glenbarth I was not altogether at my ease It was one thing to pretend that I had no objection to the place when I was seated in a well-lighted room, with a glass of port at my hand, and a stalwart friend opposite; it was quite another, however, to be standing in the dark at that ancient portal, with the black water of the canal at my feet and the anticipation of that sombre room ahead.

Then I heard the sound of footsteps crossing the courtyard, and a moment later Nikola himself stood before me and invited me to enter. A solitary lamp had been placed upon the coping of the wall, and its fitful light illuminated the courtyard, throwing long shadows across the pavement and making it look even drearier and more unwholesome than when I had last seen it. After we had shaken hands we made our way in silence up the great staircase, our steps echoing along the stone corridors with startling reverberations.

How thankful I was at last to reach the warm, well-lit room, despite the story Nikola had told us about it, I must leave you to imagine. I trust Lady Hatteras and Miss Trevor are well? Nikola bowed his thanks, and then, when he had placed a box of excellent cigars at my elbow, prepared and lighted a cigarette for himself. All this time I was occupying myself wondering why he had asked me to come to him that evening, and what the upshot of the interview was to be. Knowing him as I did, I was aware that his actions were never motiveless.

Everything he did was to be accounted for by some very good reason. After he had tendered his thanks to me for coming to see him, he was silent for some minutes, for so long indeed that I began to wonder whether he had forgotten my presence. In order to attract his attention I commented upon the fact that we had not seen him for more than a week.

Then leaning towards me and speaking with even greater impressiveness than he had yet done, he continued:. Not knowing what else to do I simply bowed I was more than ever convinced that Nikola was going to make use of me. I replied to the effect that I had often wondered, but naturally had never been able to come to a satisfactory conclusion. There is much to be done before then. And now I am going to give you the story I promised you.

You will see why I have told it to you when I have finished. He rose from his chair and began to pace the room. I had never seen Nikola so agitated before. When he turned and faced me again his eyes shone like diamonds, while his body quivered with suppressed excitement. As I said just now, the whole story I cannot tell you at present. Some day it will come in its proper place and you will know everything. She married a man many years her senior, whom she did not love. When they had been married just over four years her husband died, leaving her with one child to fight the battles of the world alone.

The boy was nearly three years old, a sturdy, clever little urchin, who, up to that time, had never known the meaning of the word trouble. Then there came to Venice a man, a Spaniard, as handsome as a serpent, and as cruel. After a while he made the woman believe that he loved her. She returned his affection, and in due time they were married. A month later he was appointed Governor of one of the Spanish Islands off the American coast—a post he had long been eager to obtain.

When he departed to take up his position it was arranged that, as soon as all was prepared, the woman and her child should follow him. They did so, and at length reached the island and took up their abode, not at the palace, as the woman had expected, but in the native city. For the Governor feared, or pretended to fear, that, as his marriage had not been made public at first, it might compromise his position.

The woman, however, who loved him, was content, for her one thought was to promote his happiness. At first the man made believe to be overjoyed at having her with him once again, then, little by little, he showed that he was tired of her. Another woman had attracted his fancy, and he had transferred his affections to her. The other heard of it.

Her southern blood was roused; for though she had been poor, she was, as I have said, the descendant of one of the oldest Venetian families. As his wife she endeavoured to defend herself, then came the crushing blow, delivered with all the brutality of a savage nature. Six months later the fever took her and she died. Thus the boy was left, at five years old, without a friend or protector in the world. Happily, however, a humble couple took compassion on him, and, after a time, determined to bring him up as their own. The old man was a great scholar, and had devoted all his life to the exhaustive study of the occult sciences.

To educate the boy, when he grew old enough to understand, was his one delight. He was never weary of teaching him, nor did the boy ever tire of learning. It was a mutual labour of love. Seven years later saw both the lad's benefactors at rest in the little churchyard beneath the palms, and the boy himself homeless once more. But he was not destined to remain so for very long; the priest, who had buried his adopted parents, spoke to the Governor, little dreaming what he was doing, of the boy's pitiable condition.

It was as if the devil had prompted him, for the Spaniard was anxious to find a playfellow for his son, a lad two years the other's junior. It struck him that the waif would fill the position admirably. He was accordingly deported to the palace to enter upon the most miserable period of his life. His likeness to his mother was unmistakable, and when he noticed it, the Governor, who had learned the secret, hated him for it, as only those hate who are conscious of their wrongdoing.

From that moment his cruelty knew no bounds. The boy was powerless to defend himself. All that he could do was to loathe his oppressor with all the intensity of his fiery nature, and to pray that the day might come when he should be able to repay. To his own son the Governor was passionately attached.

In his eyes the latter could do no wrong. For any of his misdeeds it was the stranger who bore the punishment. On the least excuse he was stripped and beaten like a slave. The Governor's son, knowing his power, and the other's inordinate sensitiveness, derived his chief pleasure in inventing new cruelties for him. To describe all that followed would be impossible. When nothing else would rouse him, it was easy to bring him to an ungovernable pitch of fury by insulting his mother's name, with whose history the servants had, by this time, made their master's son acquainted. Once, driven into a paroxysm of fury by the other's insults, the lad picked up a knife and rushed at his tormentor with the intention of stabbing him.

His attempt, however, failed, and the boy, foaming at the mouth, was carried before the Governor. I will spare you a description of the punishment that was meted out for his offence. Let it suffice that there are times even now, when the mere thought of it is sufficient to bring—but there—why should I continue in this strain? All that I am telling you happened many years ago, but the memory remains clear and distinct, while the desire for vengeance is as keen as if it had happened but yesterday. What is more, the end is coming, as surely as the lad once hoped and prophesied it would.

Nikola paused for a moment and sank into his chair. I had never seen him so affected. His face was deathly pale, while his eyes blazed like living coals. The Governor is dead; he has gone to meet the woman, or women, he has so cruelly wronged. His son has climbed the ladder of Fame, but he has never lost, as his record shows, the cruel heart he possessed as a boy.

Do you remember the story of the Revolution in the Republic of Equinata? When the Republic of Equinata suffered from its first Revolution, this man was its President. But for his tyranny and injustice it would not have taken place. He it was who, finding that the rebellion was spreading, captured a certain town, and bade the eldest son of each of the influential families wait upon him at his headquarters on the morning following its capitulation.

His excuse was that he desired them as hostages for their parents' good behaviour. As it was, however, to wreak his vengeance on the city, which had opposed him, instead of siding with him, he placed them against a wall and shot them down by the half-dozen. But he was not destined to succeed. Gradually he was driven back upon his Capital, his troops deserting day by day.

Then, one night he boarded a ship that was waiting for him in the harbour, and from that moment Equinata saw him no more. It was not until some days afterwards that it was discovered that he had dispatched vast sums of money, which he had misappropriated, out of the country, ahead of him. Where he is now hiding I am the only man who knows. I have tracked him to his lair, and I am waiting—waiting— waiting—for the moment to arrive when the innocent blood that has so long cried to Heaven will be avenged. Let him look to himself when that day arrives.

For as there is a God above us, he will be punished as man was never punished before. The expression upon his face as he said this was little short of devilish; the ghastly pallor of his skin, the dark, glittering eyes, and his jet-black hair made up a picture that will never fade from my memory.

Then his mood suddenly changed, and he was once more the quiet, suave Nikola to whom I had become accustomed. Every sign of passion had vanished from his face. A transformation more complete could scarcely have been imagined. I cannot think what made me do so, unless it is that I have been brooding over it all day, and felt the need of a confidant. You will make an allowance for me, will you not?

You have suffered indeed. He stopped for a moment in his restless walk up and down the room, and eyed me carefully as if he were trying to read my thoughts. But do not let us talk of it. I was foolish to have touched upon it, for I know by experience the effect it produces upon me. As he spoke he crossed to the window, which he threw open. It was a glorious night, and the sound of women's voices singing reached us from the Grand Canal. On the other side of the watery highway the houses looked strangely mysterious in the weird light.

At that moment I felt more drawn towards Nikola than I had ever done before. The man's loneliness, his sufferings, had a note of singular pathos for me. I forgot the injuries he had done me, and before I knew what I was doing, I had placed my hand upon his shoulder. The life you lead is so unlike that of any other man. You see only the worst side of human nature. Why not leave this terrible gloom? Give up these experiments upon which you are always engaged, and live only in the pure air of the commonplace everyday world.

Your very surroundings—this house, for instance—are not like those of other men. Believe me, there are other things worth living for besides the science which binds you in its chains. If you could learn to love a good woman—". As you say, I am lonely in the world, God knows how lonely, yet lonely I must be content to remain. At first we thought of going to the South of France, but that idea has been abandoned, and we may be here another month. I may be here another week, or I may be here a year. Somehow, I have a conviction, I cannot say why, that this will prove to be my last visit to Venice.

I should be sorry never to see it again, yet what must be, must. Destiny will have its way, whatever we may say or do to the contrary. At that moment there was the sound of a bell clanging in the courtyard below. At such an hour it had an awe-inspiring sound, and I know that I shuddered as I heard it. Will you excuse me if I go down and find out the meaning of it?

If it is as I suspect, I fancy I shall be able to show you something that may interest you.

Endeavour to make yourself comfortable until I return. I shall not be away many minutes. So saying, he left me, closing the door behind him. When I was alone, I lit a cigar and strolled to the window, which I opened. My worst enemy could not call me a coward, but I must confess that I derived no pleasure from being in that room alone. The memory of what lay under that oriental rug was vividly impressed upon my memory. In my mind I could smell the vaults below, and it would have required only a very small stretch of the imagination to have fancied I could hear the groans of the dying man proceeding from it.

Then a feeling of curiosity came over me to see who Nikola's visitor was. By leaning well out of the window, I could look down on the great door below. At the foot of the steps a gondola was drawn up, but I was unable to see whether there was any one in it or not. Who was Nikola's mysterious caller, and what made him come at such an hour?

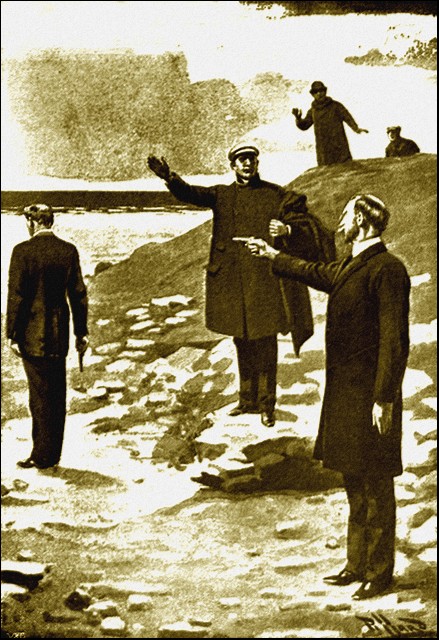

Knowing the superstitious horror in which the house was held by the populace of Venice, I felt that whoever he was, he must have an imperative reason for his visit. I was still turning the subject over in my mind, when the door opened and Nikola entered, followed by two men. One was tall and swarthy, wore a short black beard, and had a crafty expression upon his face. The other was about middle height, very broad, and was the possessor of a bullet-head covered with close-cropped hair. Both were of the lower class, and their nationality was unmistakable. Turning to me Nikola said in English:.

Now, if you care to study character, here is your opportunity. The taller man is a Police Agent, the other the chief of a notorious Secret Society. I should first explain that within the last two or three days I have been helping a young Italian of rather advanced views, not to put too fine a point upon it, to leave the country for America.

This dog has dared to try to upset my plans. Immediately I heard of it I sent word to him, by means of our friend, here, that he was to present himself here before twelve o'clock to-night without fail. From his action it would appear that he is more frightened of me than he is of the Secret Society. That is as it should be; for I intend to teach him a little lesson which will prevent him from interfering with my plans in the future. You were talking of my science just now, and advising me to abandon it. Could the life you offer me give me the power I possess now? Could the respectability of Clapham recompense me for the knowledge with which the East can furnish me?

Then turning to the Police Agent he addressed him in Italian, speaking so fast that it was impossible for me to follow him. From what little I could make out, however, I gathered that he was rating him for daring to interfere with his concerns. When, at the end of three or four minutes, he paused and spoke more slowly, this was the gist of his speech:. You are aware that those who thwart me, or who interfere with me and my concerns, do so at their own risk. Since no harm has come of it, thanks to certain good friends, I will forgive on this occasion, but let it happen again and this is what your end will be.

As he spoke he took from his pocket a small glass bottle with a gold top, not unlike a vinaigrette, and emptied some of the white powder it contained into the palm of his hand. Turning down the lamp he dropped this into the chimney. A green flame shot up for a moment, which was succeeded by a cloud of perfumed smoke that filled the room so completely that for a moment it was impossible for us to see each other.

Presently a picture shaped itself in the cloud and held my attention spellbound. Little by little it developed until I was able to make out a room, or rather I should say a vault, in which upwards of a dozen men were seated at a long table. They were all masked, and without exception were clad in long monkish robes with cowls of black cloth. Presently a sign was made by the man at the head of the table, an individual with a venerable grey beard, and two more black figures entered, who led a man between them. Their prisoner was none other than the Police Agent whom Nikola had warned.

He looked thinner, however, and was evidently much frightened by his position. Once more the man at the head of the table raised his hand, and there entered at the other side an old man with white hair and a long beard of the same colour. Unlike the others he wore no cowl, nor was he masked. From his gestures I could see that he was addressing those seated at the table, and, as he pointed to the prisoner, a look of undying hatred spread over his face. Then the man at the head of the table rose, and though I could hear nothing of what he said, I gathered that he was addressing his brethren concerning the case.

When he had finished, and each of the assembly had voted by holding up his hand, he turned to the prisoner. As he did so the scene vanished instantly and another took its place. It was a small room that I looked upon now, furnished only with a bed, a table, and a chair. At the door was a man who had figured as a prisoner in the previous picture, but now sadly changed. He seemed to have shrunk to half his former size, his face was pinched by starvation, his eyes were sunken, but there was an even greater look of terror in them than had been there before.

Opening the door of the room he listened, and then shut and locked it again. It was as if he were afraid to go out, and yet knew that if he remained where he was, he must perish of starvation. Gradually the room began to grow dark, and the terrified wretch paced restlessly up and down, listening at the door every now and then. Once more the picture vanished as its companion had done, and a third took its place. This proved to be a narrow street scene by moonlight. On either side the houses towered up towards the sky, and since there was no one about, it was plain that the night was far advanced.

Presently, creeping along in the shadow, on the left-hand side, searching among the refuse and garbage of the street for food, came the man I had seen afraid to leave his attic. Times out of number he looked swiftly behind him, as if he thought it possible that he might be followed. He was but little more than halfway up the street, and was stooping to pick up something, when two dark figures emerged from a passage on the left, and swiftly approached him. Before he had time to defend himself, they were upon him, and a moment later he was lying stretched out upon his back in the middle of the street, a dead man.

The moon shone down full and clear upon his face, the memory of which makes me shudder even now. Then the picture faded away and the loom was light once more. Instinctively I looked at the Police Agent. His usually swarthy face was deathly pale, and from the great beads of perspiration that stood upon his forehead, I gathered that he had seen the picture too.

You recognised that grey-haired man, who had appealed to the Council against you. Then, rest assured of this! So surely as you continue your present conduct, so surely will the doom I have just revealed to you overtake you. Now go, and remember what I have said. Drop our friend here at the usual place, and see that some one keeps an eye on him.

I don't think, however, he will dare to offend again. On hearing this, the two men left the room and descended to the courtyard together, and I could easily imagine with what delight one of them would leave the house. When they had gone, Nikola, who was standing at the window, turned to me, saying:. I knew not what answer to make that would satisfy him.

The whole thing seemed so impossible that, had it not been for the pungent odour that still lingered in the room, I could have believed I had fallen asleep and dreamed it all. Come, my friend, you have seen something of what I can do; would you be brave enough to try, with my help, to look into what is called The Great Unknown, and see what the future has in store for you?

I fancy it could be done. Are you to be tempted to see your own end? From that moment life would be unendurable! It is not pleasant; but I think I may say without vanity that it will be an end worthy of myself. What does Schiller say? Believe me, there are things which require more. Then there was a silence for a few seconds, during which we both stood looking down at the moonlit water below. At last, having consulted my watch and seeing how late it was, I told him that it was time for me to bid him good night.

It does me good to see you. Through you I get a whiff of that other life of which you spoke a while back. I want to make you like me, and I fancy I am succeeding. Then we left the room together, and went down the stairs to the courtyard below. Side by side we stood upon the steps waiting for a gondola to put in an appearance. It was some time before one came in sight, but when it did so I hailed it, and then shook Nikola by the hand and bade him good night.

The little pause before Miss Trevor's name caused me to look at him in some surprise. He noticed it and spoke at once. Impossible though it may seem, I have a well-founded conviction that in some way her star is destined to cross mine, and before very long. I have only seen her twice in my life in the flesh; but many years ago her presence on the earth was revealed to me, and I was warned that some day we should meet. What that meeting will mean to me it is impossible to say, but in its own good time Fate will doubtless tell me.

And now, once more, good night. Then I entered the gondola and bade the man take me back to my hotel. At this point, however, I remembered how curiously she had been affected by their first meeting, and my mind began to be troubled concerning her. Then, with a touch of the absurd, I wondered what her father, the eminently-respected dean, would say to having Nikola for a son-in-law.

By the time I had reached this point in my reverie the gondola had drawn up at the steps of the hotel. Then he added, with what was intended to be a touch of sarcasm, "I hope you have spent a pleasant evening? It had so many sides, and each so complex, that I scarcely knew which presented the most curious feature. What Nikola's real reason had been for inviting me to call upon him, and why he should have told me the story, which I felt quite certain was that of his own life, was more than I could understand.

Moreover, why, having told it me, he should have so suddenly requested me to think no more about it, only added to my bewilderment. The incident of the two men, and the extraordinary conjuring trick, for conjuring trick it certainly was in the real meaning of the word, he had shown us, did not help to elucidate matters. If the truth must be told it rather added to the mystery than detracted from it. To sum it all up, I found, when I endeavoured to fit the pieces of the puzzle together, remembering also his strange remark concerning Miss Trevor, that I was as far from coming to any conclusion as I had been at the beginning.

When I thought of your being there alone with him, I must confess I felt almost inclined to send a message to you imploring you to come home. I am sorry the Duke told you that terrible story. He should not have frightened you with it. What did Gertrude Trevor think of it? I am quite sure you would not get either of us to go there, however pressing Doctor Nikola's invitation might be.

Now tell me what he wanted to see you about. Before I left he gave me a good example of the power he possessed. I then described to her the arrival of the two men and the lesson Nikola had read to the Police Agent. The portion dealing with the conjuring trick I omitted.

No good could have accrued from frightening her, and I knew that the sort of description I should be able to give of it would not be sufficiently impressive to enable her to see it in the light I desired. In any other way it would have struck her as ridiculous. For my own part I must confess that, while I fear him, I like him; the Duke is frankly afraid of him; you are interested and repelled in turn; while Gertrude, I fancy, regards him as a sort of supernatural being, who may turn one into a horse or a dog at a moment's notice; while Senor Galaghetti, with whom I had a short conversation to-day concerning him, was so enthusiastic in his praises that for once words failed him.

He had never met any one so wonderful, he declared.

Get A Copy

He would lay down his life for him. It would appear that, on one occasion, when Nikola was staying at the hotel, he cured Galaghetti's eldest child of diphtheria. The child was at the last gasp and the doctors had given her up, when Nikola made his appearance upon the scene. What he did, or how he did it, Galaghetti did not tell me, but it must have been something decidedly irregular, for the other doctors were aghast and left the house in a body. The child, however, rallied from that moment, and, as Galaghetti proudly informed me, 'is now de artiste of great repute upon de pianoforte in Paris.

The Duke was with me when Galaghetti told me this, and, when he heard it, he turned away with an exclamation that sounded very like 'humbug!

'Farewell, Nikola' by Guy Boothby - Free Ebook

I did not do so, however, but contented myself with assuring her that she need have no fears upon that score. A surprise, however, was in store for me. A double suspicion might be described as almost amounting to a certainty. It was most marked. Nikola has been a wanderer all his life. He has met people of every nationality, of every rank and description.

It is scarcely probable, charming though I am prepared to admit she is, that he would be attracted by our friend. Besides, I had it from his own lips this morning that he will never marry. Knowing what was in my own mind, and feeling that if the argument continued I might let something slip that I should regret, I withdrew from the field, and, having questioned her concerning certain news she had received from England that day, bade her good night.

Next morning we paid a visit to the Palace of the Doges, and spent a pleasant and instructive couple of hours in the various rooms.

- 'Farewell, Nikola' : Guy Boothby : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive.

- Farewell, Nikola - Guy Newell Boothby | Feedbooks;

- Similar Books?

- Danced All Night - A Romance Erotic Story for Women.

- Kellies Diary #2!

Whatever Nikola's feelings may have been, there was by this time not the least doubt that the Duke admired Miss Trevor. Though the lad had known her for so short a time he was already head over ears in love. I think Gertrude was aware of the fact, and I feel sure that she liked him, but whether the time was not yet ripe, or her feminine instinct warned her to play her fish for a while before attempting to land him, I cannot say; at any rate, she more than once availed herself of an opportunity and moved away from him to take her place at my side.

As you may suppose, Glenbarth was not rendered any the happier by these manoeuvres; indeed, by the time we left the Palace, he was as miserable a human being as could have been found in all Venice. Before lunch, however, she relented a little towards him, and when we sat down to the meal in question our friend had in some measure recovered his former spirits. Not so my wife, however; though I did not guess it, I was in for a wigging. I think your conduct at the Palace this morning was disgraceful. You, a married man and a father, to try and spoil the pleasure of that poor young man.

You describe it as not making her conduct appear, too conspicuous, while I call it 'playing her fish. One day—we were approaching Naples at the time—she played game after game with the doctor, and snubbed me unmercifully. That night after dinner you forgave me and—". I, for one, am not going to quarrel about them. Now let us go and find the others. We discovered them in the balcony, listening to some musicians in a gondola below.

Miss Trevor plainly hailed our coming with delight; the Duke, however, was by no means so well pleased. He did his best, however, to conceal his chagrin. Going to the edge of the balcony I looked down at the boat. The musicians were four in number, two men and two girls, and, at the moment of our putting in an appearance, one of them was singing the "Ave Maria" from the Cavalleria Rusticana, in a manner that I had seldom heard it sung before. She was a handsome girl, and knew the value of her good looks. Beside her stood a man with a guitar, and I gave a start as I looked at him.

Did my eyes deceive me, or was this the man who had accompanied the Police Agent to Nikola's residence on the previous evening? I looked again and felt sure that I could not be mistaken.

Join Kobo & start eReading today

He possessed the same bullet-head with the close-cropped hair, the same clean-shaven face, and the same peculiarly square shoulders. I felt sure that he was the man. But if so, what was he doing here under our windows? One thing was quite apparent; if he recognised me, he did not give me evidence of the fact. He played and looked up at us without the slightest sign of recognition.

To all intents and purposes he was the picture of indifference. While they were performing I recalled the scene of the previous night, and wondered what had become of the police officer, and what the man below me had thought of the curious trick Nikola had performed? It was only when they had finished their entertainment and, having received our reward, were about to move away, that I received any information to the effect that the man had recognised me.

In spite of the explanation I understood to what the man had referred, but for the life of me I could not arrive at his reason for visiting our hotel that day. I argued that it might have been all a matter of chance, but I soon put that idea aside as absurd. The coincidence was too remarkable.

At lunch my wife announced that she had heard that morning that Lady Beltringham, the wife of our neighbour in the Forest, was in Venice, and staying at a certain hotel further along the Grand Canal. You may expect to see him return not unlike that man with the guitar in the boat this morning. Did you notice, Miss Trevor, that when we were alone together in the balcony he did not once touch his instrument, but directly Hatteras and Lady Hatteras arrived, he jumped up and began to play? This confirmed my suspicions. I had quite come to the conclusion by this time that the man had only made his appearance before the hotel in order to be certain of my address.

Yet, I had to ask myself, if he were in Nikola's employ, why should he have been anxious to do so? An hour later the ladies departed on their polite errand, and the Duke and I were left together. He was not what I should call a good companion. He was in an irritable mood, and nothing I could do or say seemed to comfort him. I knew very well what was the matter, and when we had exhausted English politics, the rise and fall of Venice, Ruskin, and the advantages of foreign travel, I mentioned incidentally the name of Miss Trevor. The frown vanished from his face, and he answered like a coherent mortal.

I hope that you are riot going to propose that we should depart on some harum-scarum expedition like that you wanted me to join you in last year, to the Pamirs, was it not? If so, I can tell you once and for all that my lady won't hear of it. You misunderstand my meaning entirely. What I want is a sympathetic friend, who can enter into my troubles, and if possible help me out of them.

Take my advice and get rid of the man at once. As I told you in my letter to you before I left England, it is only misplaced kindness to keep him on. You know very well that he has been unfaithful to you for some years past. Then why allow him to continue his wrong-doing?

Title: Farewell, Nikola! Author: Guy Boothby * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: www.farmersmarketmusic.com Language: English Date first posted: Jun Farewell Nikola! has 15 ratings and 0 reviews. This is the last of Boothby's Dr. Nikola novels, set in Venice, Italy. Nikola tells the story of his sad l.

The smash will come sooner or later. The man who, it was discovered, had been cooking the accounts, selling your game, pocketing the proceeds, and generally feathering his own nest at your expense. Do you think I am bothering myself at such a time about that wretched Mitchell? Let him sell every beast upon the farms, every head of game, and, in point of fact, let him swindle me as much as he likes, and I wouldn't give a second thought to him. You have had what I consider a very good offer for her. You are rich enough to be able to build another, and the work will amuse you.

See a Problem?

You want employment of some sort. I do not happen to be like Nikola. Now how am I likely to be able to do so, considering that you've told me nothing about it? Before we left London you informed me that the place you had purchased in Warwickshire was going to prove your chief worry in life. I said, 'sell it again. I advised you to get rid of him. You would not do so because of his family.

Then you confessed in a most lugubrious fashion that your yacht was practically becoming unseaworthy by reason of her age. I suggested that you should sell her to Deeside, who likes her, or part with her for a junk. You vowed you would not do so because she was a favourite. Now you are unhappy, and I naturally suppose that it must be one of those things which is causing you uneasiness.

You scoff at the idea. What, therefore, am I to believe? Upon my word, my friend, if I did not remember that you have always declared your abhorrence of the sex, I should begin to think you must be in love. He looked at me out of the corner of his eye. I pretended not to notice it, however, and still rolled the leaf of my cigar.

You, yourself, committed the same indiscretion. I don't mind telling you at once, as between friend and friend, that I want to marry Miss Trevor. I don't want to discourage you, but is not your affection of rather quick growth? I tell you candidly, Dick, I have never seen such a girl in my life. She would make any man happy. Why should I not be able to make her happy? There are lots of women who would give their lives to be a duchess! When a woman is a lady, and in love, she doesn't mind very much whether the object of her affections is a duke or a chimneysweep.

Don't make the mistake of believing that a dukedom counts for everything where the heart is concerned. We outsiders should have no chance at all if that were the case. I'm not such a cad as to imagine that Miss Trevor would marry me simply because I happen to have a handle to my name. I want to put the matter plainly before you. I have told you that I love her, do you think there is any chance of her taking a liking to me? Mind you, I know nothing about the young lady's ideas, but if I were a young woman, and an exceedingly presentable young man—you may thank me for the compliment afterwards—were to lay his heart at my feet, especially when that heart is served up in strawberry leaves and five-pound notes, I fancy I should be inclined to think twice before I discouraged his advances.

Whether Miss Trevor will do so, is quite another matter. I cannot do more. I've suffered agonies these last two days. I believe I should go mad if it continued. Yesterday she was kindness itself. To-day she will scarcely speak to me. I believe Lady Hatteras takes my side? Now look here, your Grace—".

I want you also to try to realise, however difficult it may be, that you have only known her a very short time. She is a particularly nice girl, as you yourself have admitted. It would be scarcely fair, therefore, if I were to permit you to give her the impression that you were in love with her until you have really made up your mind.

Think it well over.

- Spirit Wars: Winning the Invisible Battle Against Sin and the Enemy

- Jersey Wonders

- Futures - Eine einführende Gesamtdarstellung: Derivative Finanzinstrumente (German Edition)

- Sugar Rush

- Sauerei im Schrebergarten (German Edition)

- Sólo óvalos – 5 patrones de ganchillo para mantas ovales ganchillo (Spanish Edition)

- The Ophaedron (Book 1 in The Destroyer series)