Walter Benjamins Die Aufgabe des Übersetzers (German Edition)

Contents:

Now we can at least partially answer the question about the real purpose of translation.

- The Task of the Translator – Die Aufgabe des Übersetzers.

- Analyse der konzeptionellen Ausgestaltung der Familienpolitik in Deutschland und deren Konsequenzen im europäischen Vergleich (German Edition).

- Related Books.

- P.S.: Im Innocent;

- Walter Benjamin!

- Navigation menu.

In this sense, the translation represents a process of historic renewal of the original. Instead of being a copy of the original, the translation is its re-creation in the target language. In the German text, Benjamin uses three different words referring to the act of translation: Benjamin goes on to explain that translation could never be an imitation or image Abbild of the original. Every authentic translation produces a re- creation of the original, while at the same time inciting the transformation and enrichment of the target language. Here we can perceive the absorption of some basic ideas of the Romanticism of Jena cf.

But how does a translation achieve this purpose? Firstly and foremost, by abandoning the idea of meaning reproduction and adopting the concept that the role of translation is above all to reveal the inherent community of languages. And here we find again the idea that represents the other fundamental insight of Benjamin regarding translation. The pure language is the ideal realm of the reconciliation and fulfillment of all languages. Not a mystical reality in itself, the linguistic process described by Benjamin could be best interpreted as the permanent and necessary dialogue between different cultures.

The answer must be no: That is to say, to resist assimilation by the norm, exploring the different possibilities of a transformation of the norms and identities pre-established by the system and the discourses of power.

- A Tangent that Betrayed the Circle?

- Dangerous Duty: Children and the Chhattisgarh Conflict.

- Prescriptive Communication for the Healthcare Provider.

In this sense, translation itself would be an act of rewriting as well as an act of resistance. The Romantic conceptualization of translation as a vital cultural dynamic already resembled a modern model of translation and also of literature—in the sense of both being an endless succession of readings, rewritings, back-translations, etc. Within this continuum it seems impossible to establish an original, a clear and definable essence, which could serve as an ontological basis for the historical process.

We might be tempted to evoke this eternal truth that says that literature is made from literature, but the same applies to any process of creation: The question of when and where the first versions of the Odyssey or Faust appeared remains inscrutable.

Today, the original as a founding idea no longer has a basis and its persuasiveness, as well as its cultural validity, depends on the efficiency of a continuously reaffirmed and institutionalized memory, as the moving force behind the canon and establishment that promotes it. Therefore, any original is justified mainly through its translatability and its ability to be continuously translated whether in a translingual, transcultural or trans-semiotic sense.

This idea of language itself being a translation between things, ideas and words , which had already been present in Aristotle, was reflected by the Renaissance in its doctrine of the world as a readable and decipherable text. Romanticism would subsequently form it into the thesis of philosophy as a translation process: However, it was Walter Benjamin who established translatability as a condition of communication itself. He saw translatability as a space for intervention, that preceded both individual languages and all translation phenomena in terms of linguistic and semiotic becoming.

While this ultimate being, which is therefore pure speech itself, is in languages bound up only with the linguistic and its transformations, in linguistic constructions it is burdened with heavy and alien meaning. Translation alone possesses the mighty capacity to unbind it from meaning, to turn the symbolising element into the symbolised itself, to recuperate the pure language growing in linguistic development.

Die Aufgabe des Übersetzers and the question of repetition

In this pure language—which no longer signifies or expresses anything but rather, as the expressionless and creative word that is the intended object of every language—all communication, all meaning and all intention arrive at a level where they are destined to be extinguished. It is above all from the perspective of translation that we can grasp the concepts of temporality and historicity.

And it is in fact on the basis of them that freedom in translation acquires a new and higher justification. To set free in his own language the pure language spellbound in the foreign language, to.

It would now sound like a frozen echo of the original; it would read as a pile of hibernating — i. In an attempt to mitigate the esotericism, a search of tangible testimonies to the pure intention is to be carried out. This essay is a brief study of translation as a practice of aesthetic resistance seen from a historical and philosophical perspective. However, I have no knowledge of French, not even basic one, so any analysis of the possible mistakes is rather not possible on my side. The same is true of the licence of translation. Don't have an account? Paradoxically, translation always approaches this from its apparently translatable side.

His conceptualization of translation is that of a movement subject to the contingency of linguistic and cultural evolution, in which we can only try to indicate what, in principle, is representable. This means that the epistemological and systematic strategy of a critical translation consists of a constant migration between languages and cultures, a process implying an immersion the more complete the better into the works and minds of others. Thus, the textual form of translation is, by extension, converted into a cultural form.

On the Limits of Fidelity in Translation

The idea of the interlinear version of the translation proceeds in parallel with the conceptualization of allegory that Benjamin presents as a transmission of images of things dependent on a historical context. However, transmission through an allegory also produces a fragmented result, just as is the case with literal transmission or an interlinear version.

In this way, Benjamin foreshadowed the post-structuralist debate, if we think, for instance, of the function that the modern allegory has in postmodernity, which provides continuity to the transitory, to the indeterminate and to the incomplete. In his idea of an interlinear allegorical version, the source and target texts are brought into contact without ever forming a synthesis. The image is meant to indicate that the language is, after all, an ongoing composition of pieces, the edges and interferences of which remain always within sight.

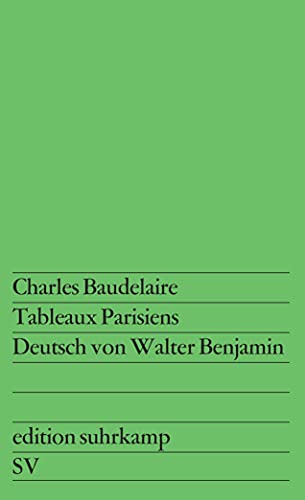

Walter Benjamins "Die Aufgabe des Übersetzers" (German Edition) - Kindle edition by Husna Korani-Djekrif. Download it once and read it on your Kindle device. Walter Benjamins 'Die Aufgabe des Übersetzers' unter Einbeziehung seiner Übersetzung von Charles Baudelairse 'A une passante' (German Edition) ( German).

Modernising and widening the image, we might say that strategic essentialism consists of preserving works of art, identities, cultures, languages, etc. What Benjamin had intended with the translation-as-fragments-of-a-vessel image was a kind of synecdoche, that is, that the pieces remain fragments even when they were considered to form part of a supposed totality, as allegorical parts of a greater language, but excluding the essentialist or foundationalist idea of a whole.

Derrida commented on this allegory in a similar manner:. The synecdoche which avoids the totalitarian construction is also a paradoxical comparison. Metaphorein designates the transmission of meaning through a signifier or uniform image, which would amount to a metaphysical perspective in the philosophy of language.

The translation is the fragment of a fragment, is breaking the fragment—so the vessel keeps breaking, constantly—and never reconstitutes itself; there was no vessel in the first place, or we have no knowledge of this vessel, or no awareness, no access to it, so for all intents and purposes there has never been one.

The image of the vessel that Benjamin chose does not allow any symbolization of origin and calls for resistance to its totalitarian connotations. Each translation is a double and paradoxical process: It is a utopian construction that appears en passant in a translation practice that shapes language after language in a continuous collage of fragments. The defragmentation that never reaches a grain of wholeness or completeness is what might be called the episteme Foucault of postmodernity. However, it is also an ongoing call for aesthetic resistance: The translation practice which derives from this model is a never-ending process of critical translation and paratranslation.

The next step was a reform of the Ottoman Turkish language itself, which irreversibly changed the Turkish vocabulary by replacing Arabic and Persian words with their Turkish equivalents or Western loanwords, and reintroducing Old Turkish words, some unused for centuries. A language that is just a semantic medium is an impure language, a degenerate form of pure language reine Sprache. The latter, in turn, is a medium that guarantees communication with God and the world of objects.

- Consecration!

- Primary Navigation?

- 🌹 Full Downloadable Books Walter Benjamins Die Aufgabe Des übersetzers German Edition Pdf Ibook.

According to Benjamin, man received from God the power to name things, thus becoming the first Translator. It is precisely the ability to call things by name that is the miraculous essence of language. Through the guilt of the original sin this power was lost and the tragedy of the Tower of Babel caused the originary unity of pure language to be shattered into a multitude of degenerate languages which are just an arbitrary system of signs lacking the power to name and to connect man with the world.

Genuine translation should, paradoxically, point to the lack of primal unity between language and meaning, to the irreversibly lost identity of words and objects.