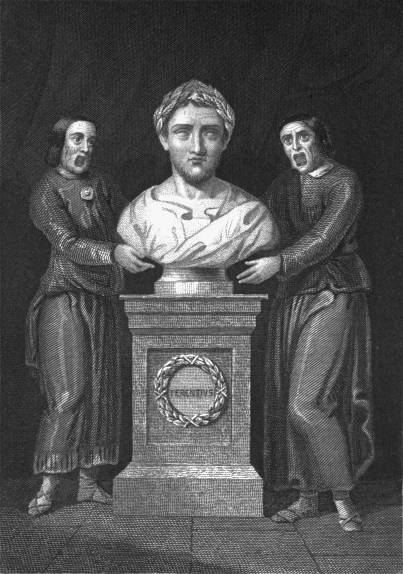

The Comedies of Terence and THE FABLES OF PHÆDRUS By HENRY THOMAS RILEY, B.A.

Demetrius and Menander II. The Man and the Ass V. The Buffoon and Countryman VI. The Emblem of Opportunity IX. The Bull and the Calf X. The Ape and the Fox II. The Author III. Mercury and the two Women IV.

Item Preview

Prometheus and Cunning V. The Author VI. Aesop and the Author IX. Pompeius Magnus and his Soldier X. Juno, Venus, and the Hen XI. The Widow and the Soldier XV. The Beaver XXX. The Sick Kite II. Jupiter and the Fox IV. The Lion and the Mouse V. The Man and the Trees VI. The Snail and the Ape IX. The Ass fawning upon his Master XI. But if any one shall think fit to cavil, because not only wild beasts, but even trees speak, let him remember that we are disporting in fables.

Driven by thirst, a Wolf and a Lamb had come to the same stream; the Wolf stood above, and the Lamb at a distance below. Then, the spoiler, prompted by a ravenous maw, alleged a pretext for a quarrel. The water is flowing downwards from you to where I am drinking.

This Fable is applicable to those men who, under false pretences, oppress the innocent. When Athens[1] was flourishing under just laws, liberty grown wanton embroiled the city, and license relaxed the reins of ancient discipline. Upon this, the partisans of factions conspiring, Pisistratus the Tyrant[2] seized the citadel.

When the Athenians were lamenting their sad servitude not that he was cruel, but because every burden is grievous to those who are unused to it , and began to complain, Aesop related a Fable to the following effect: Having got the better of their fears, vying with each other, they swim towards him, and the insolent mob leap upon the Log.

After defiling it with every kind of insult, they sent to Jupiter, requesting another king, because the one that had been given them was useless. Upon this, he sent them a Water Snake,[3] who with his sharp teeth began to gobble them up one after another. Helpless they strive in vain to escape death; terror deprives them of voice. By stealth, therefore, they send through Mercury a request to Jupiter, to succour them in their distress. Then said the God in reply: This probably alludes to the government of Solon, when Archon of Athens.

Pisistratus the Tyrant —Ver. From Suidas and Eusebius we learn that Aesop died in the fifty-fourth Olympiad, while Pisistratus did not seize the supreme power at Athens till the first year of the fifty-fifth. These dates, however, have been disputed by many, and partly on the strength of the present passage. Pliny tells us that the "hydrus" lives in the water, and is exceedingly venomous. Some Commentators think that Phaedrus, like Aesop, intends to conceal a political meaning under this Fable, and that by the Water-Snake he means Caligula, and by the Log, Tiberius.

Others, perhaps with more probability, think that the cruelty of Tiberius alone is alluded to in the mention of the snake. Indeed, it is doubtful whether Phaedrus survived to the time of Caligula: That one ought not to plume oneself on the merits which belong to another, but ought rather to pass his life in his own proper guise, Aesop has given us this illustration: They tore his feathers from off the impudent bird, and put him to flight with their beaks.

Then said one of those whom he had formerly despised: A Jackdaw, swelling —Ver. Scheffer thinks that Sejanus is alluded to under this image. He who covets what belongs to another, deservedly loses his own. As a Dog swimming —Ver. Lessing finds some fault with the way in which this Fable is related, and with fair reason. The Dog swimming would be likely to disturb the water to such a degree, that it would be impossible for him to see with any distinctness the reflection of the meat. The version which represents him as crossing a bridge is certainly more consistent with nature.

An alliance with the powerful is never to be relied upon: When they had captured a Stag of vast bulk, thus spoke the Lion, after it had been divided into shares: And a Sheep —Ver. Lessing also censures this Fable on the ground of the partnership being contrary to nature; neither the cow, the goat, nor the sheep feed on flesh. I am the strongest —Ver. Some critics profess to see no difference between "sum fortis" in the eighth line, and "plus valeo" here; but the former expression appears to refer to his courage, and the latter to his strength.

However, the second and third reasons are nothing but reiterations of the first one, under another form. Davidson remarks on this passage: Aesop, on seeing the pompous wedding of a thief, who was his neighbour, immediately began to relate the following story: Once on a time, when the Sun was thinking of taking a wife,[8] the Frogs sent forth their clamour to the stars. Disturbed by their croakings, Jupiter asked the cause of their complaints. What is to become of us, if he beget children? Taking a wife —Ver.

It has been suggested by Brotier and Desbillons, that in this Fable Phaedrus covertly alludes to the marriage which was contemplated by Livia, or Livilla, the daughter of the elder Drusus and Antonia, and the wife of her first-cousin, the younger Drusus, with the infamous Sejanus, the minister and favourite of Tiberius, after having, with his assistance, removed her husband by poison.

In such case, the Frogs will represent the Roman people, the Sun Sejanus, who had greatly oppressed them, and by Jupiter, Tiberius will be meant. A Fox, by chance, casting his eyes on a Tragic Mask: Has no brains —Ver. To make the sense of this remark of the Fox the more intelligible, we must bear in mind that the ancient masks covered the whole head, and sometimes extended down to the shoulders; consequently, their resemblance to the human head was much more striking than in the masks of the present day.

He who expects a recompense for his services from the dishonest commits a twofold mistake; first, because he assists the undeserving, and in the next place, because he cannot be gone while he is yet safe. A bone that he had swallowed stuck in the jaws of a Wolf. Thereupon, overcome by extreme pain, he began to tempt all and sundry by great rewards to extract the cause of misery.

At length, on his taking an oath, a Crane was prevailed on, and, trusting the length of her neck to his throat, she wrought, with danger to herself, a cure for the Wolf. Let us show, in a few lines, that it is unwise to be heedless[10] of ourselves, while we are giving advice to others. A Sparrow upbraided a Hare that had been pounced upon by an Eagle, and was sending forth piercing cries. To be heedless —Ver. Whoever has once become notorious by base fraud, even if he speaks the truth, gains no belief.

To this, a short Fable of Aesop bears witness. A Wolf indicted a Fox upon a charge of theft; the latter denied that she was amenable to the charge.

- Henry Thomas Riley - Wikipedia.

- Men of the West: Ten Spicy, Gay Cowboy Stories.

- My Patch: The life of Reginald Smithers, a village policeman.

- The widowing of Mrs. Holroyd; a drama in three acts!

- ?

A dastard, who in his talk brags of his prowess, and is devoid of courage,[11] imposes upon strangers, but is the jest of all who know him. A Lion having resolved to hunt in company with an Ass, concealed him in a thicket, and at the same time enjoined him to frighten the wild beasts with his voice, to which they were unused, while he himself was to catch them as they fled. Devoid of courage —Ver. Burmann suggests, with great probability, that Phaedrus had here in mind those braggart warriors, who have been so well described by Plautus and Terence, under the characters of Pyrgopolynices and Thraso.

This new cause of astonishment —Ver. Never having heard the voice of an ass in the forests before. This story shows that what you contemn is often found of more utility than what you load with praises. A Stag, when he had drunk at a stream, stood still, and gazed upon his likeness in the water. While there, in admiration, he was praising his branching horns, and finding fault with the extreme thinness of his legs, suddenly roused by the cries of the huntsmen, he took to flight over the plain, and with nimble course escaped the dogs.

Then a wood received the beast; in which, being entangled and caught by his horns, the dogs began to tear him to pieces with savage bites. While dying, he is said to have uttered these words: What grace you carry in your shape and air! If you had a voice, no bird whatever would be superior to you. Then, too late, the Raven, thus, in his stupidity overreached, heaved a bitter sigh. From a window —Ver. Burmann suggests that the window of a house in which articles of food were exposed for sale, is probably meant. By this story —Ver.

Heinsius thinks this line and the next to be spurious; because, though Phaedrus sometimes at the beginning mentions the design of his Fable, he seldom does so at the end. In this conjecture he is followed by Bentley, Sanadon, and many others of the learned. A bungling Cobbler, broken down by want, having begun to practise physic in a strange place, and selling his antidote[15] under a feigned name, gained some reputation for himself by his delusive speeches. Through fear of death, the cobbler then confessed that not by any skill in the medical art, but through the stupidity of the public, he had gained his reputation.

The King, having summoned a council, thus remarked: Selling his antidote —Ver. Trust your lives —Ver. He seems to pun upon the word "capita," as meaning not only "the life," but "the head," in contradistinction to "the feet," mentioned in the next line. In a change of government, the poor change nothing beyond the name of their master. That this is the fact this little Fable shows. A timorous Old Man was feeding an Ass in a meadow. Frightened by a sudden alarm of the enemy, he tried to persuade the Ass to fly, lest they should be taken prisoners.

But he leisurely replied: When a rogue offers his name as surety in a doubtful case, he has no design to act straight-forwardly, but is looking to mischief. A Stag asked a Sheep for a measure[17] of wheat, a Wolf being his surety. For a measure —Ver. Properly "modius;" the principal dry measure of the Romans. It was equal to one-third of the amphora, and therefore to nearly two gallons English. Liars generally[19] pay the penalty of their guilt. A Dog, who was a false accuser, having demanded of a Sheep a loaf of bread, which he affirmed he had entrusted to her charge; a Wolf, summoned as a witness, affirmed that not only one was owing but ten.

Condemned on false testimony, the Sheep had to pay what she did not owe. A few days after, the Sheep saw the Wolf lying in a pit. It is supposed by some that this Fable is levelled against the informers who infested Rome in the days of Tiberius. No one returns with good will to the place which has done him a mischief. Her months completed,[20] a Woman in labour lay upon the ground, uttering woful moans. Her Husband entreated her to lay her body on the bed, where she might with more ease deposit her ripe burden.

Navigation menu

Her months completed —Ver. Plutarch relates this, not as a Fable, but as a true narrative. The fair words of a wicked man are fraught with treachery, and the subjoined lines warn us to shun them. A Bitch, ready to whelp,[21] having entreated another that she might give birth to her offspring in her kennel, easily obtained the favour. Afterwards, on the other asking for her place back again, she renewed her entreaties, earnestly begging for a short time, until she might be enabled to lead forth her whelps when they had gained sufficient strength. Ready to whelp —Ver.

An ill-judged project is not only without effect, but also lures mortals to their destruction. Some Dogs espied a raw hide sunk in a river. In order that they might more easily get it out and devour it, they fell to drinking up the water; they burst, however, and perished before they could reach what they sought. Whoever has fallen from a previous high estate, is in his calamity the butt even of cowards. As a Lion, worn out with years, and deserted by his strength, lay drawing his last breath, a Wild Boar came up to him, with flashing tusks,[22] and with a blow revenged an old affront.

Next, with hostile horns, a Bull pierced the body of his foe. An Ass, on seeing the wild beast maltreated with impunity, tore up his forehead with his heels. I seem to die a double death. With flashing tusks —Ver. Scheffer suggests that they were so called from their white appearance among the black hair of the boar's head.

A Weasel, on being caught by a Man, wishing to escape impending death: Those persons ought to recognize this as applicable to themselves, whose object is private advantage, and who boast to the unthinking of an unreal merit. The man who becomes liberal all of a sudden, gratifies the foolish, but for the wary spreads his toils in vain.

A Thief one night threw a crust of bread to a Dog, to try whether he could be gained by the proffered victuals: You are greatly mistaken. For this sudden liberality bids me be on the watch, that you may not profit by my neglect. The needy man, while affecting to imitate the powerful, comes to ruin.

Which was the bigger —Ver. In good Latin, he says "uter" would occupy the place of "quis," and "bovem" would be replaced by "bos. Those who give bad advice to discreet persons, both lose their pains, and are laughed to scorn. It has been related,[24] that Dogs drink at the river Nile running along, that they may not be seized by the Crocodiles. Accordingly, a Dog having begun to drink while running along, a Crocodile thus addressed him: It has been related —Ver.

Pliny, in his Natural History, B. Harm should be done to no man; but if any one do an injury, this Fable shows that he may be visited with a like return. A Fox is said to have given a Stork the first invitation to a banquet, and to have placed before her some thin broth in a flat dish, of which the hungry Stork could in no way get a taste. Of minced meat —Ver. The "lagena," or "lagona," was a long-necked bottle or flagon, made of earth, and much used for keeping wine or fruit. The foreign bird —Ver. Alluding probably to the migratory habits of the stork, or the fact of her being especially a native of Egypt.

This Fable may be applied to the avaricious, and to those, who, born to a humble lot, affect to be called rich. Accordingly, while he was watching over the gold, forgetful of food, he was starved to death; on which a Vulture, standing over him, is reported to have said: This plainly refers to the custom which prevailed among the ancients, of burying golden ornaments, and even money, with the dead; which at length was practised to such an excess, that at Rome the custom was forbidden by law.

It was probably practised to a great extent by the people of Etruria; if we may judge from the discoveries of golden ornaments frequently made in their tombs. Gods the Manes —Ver. Perhaps by "Deos Manes" are meant the good and bad Genii of the deceased. Men, however high in station, ought to be on their guard against the lowly; because, to ready address, revenge lies near at hand.

The other despised her, as being safe in the very situation of the spot. The Fox snatched from an altar a burning torch, and surrounded the whole tree with flames, intending to mingle anguish to her foe with the loss of her offspring. The Eagle, that she might rescue her young ones from the peril of death, in a suppliant manner restored to the Fox her whelps in safety. Fools often, while trying to raise a silly laugh, provoke others by gross affronts, and cause serious danger to themselves.

An Ass meeting a Boar: The other indignantly rejects the salutation, and enquires why he thinks proper to utter such an untruth. The Ass, with legs[30] crouching down, replies: The ass, with legs —Ver. This line is somewhat modified in the translation. When the powerful[31] are at variance, the lowly are the sufferers. A Frog, viewing from a marsh, a combat of some Bulls: Thus does their fury concern our safety. When the powerful —Ver. This is similar to the line of Horace, "Quicquid delirant reges, plectuntur Achivi.

He who entrusts himself to the protection of a wicked man, while he seeks assistance, meets with destruction. Some Pigeons, having often escaped from a Kite, and by their swiftness of wing avoided death, the spoiler had recourse to stratagem, and by a crafty device of this nature, deceived the harmless race.

Then said one of those that were left: The plan of Aesop is confined to instruction by examples; nor by Fables is anything else[1] aimed at than that the errors of mortals may be corrected, and persevering industry[2] exert itself. Whatever the playful invention, therefore, of the narrator, so long as it pleases the ear, and answers its purpose, it is recommended by its merits, not by the Author's name. Is anything else —Ver.

Burmann thinks that the object of the Author in this Prologue is to defend himself against the censures of those who might blame him for not keeping to his purpose, mentioned in the Prologue of the First Book, of adhering to the fabulous matter used by Aesop, but mixing up with such stories narratives of events that had happened in his own time. Of the sage —Ver. To insert something —Ver. He probably alludes to such contemporary narratives as are found in Fable v. While a Lion was standing over a Bullock, which he had brought to the ground, a Robber came up, and demanded a share.

By chance, a harmless Traveller was led to the same spot, and on seeing the wild beast, retraced his steps; on which the Lion kindly said to him: A very excellent example, and worthy of all praise; but covetousness is rich and modesty in want. Modesty in want —Ver. Martial has a similar passage, B. A Woman, not devoid of grace, held enthralled a certain Man of middle age,[6] concealing her years by the arts of the toilet: Both, as they were desirous to appear of the same age with him, began, each in her turn, to pluck out the hair of the Man.

While he imagined that he was made trim by the care of the women, he suddenly found himself bald; for the Young Woman had entirely pulled out the white hairs, the Old Woman the black ones. Of middle age —Ver 8. It has been a matter of doubt among Commentators to which "aetatis mediae" applies—the man or the woman. But as she is called "anus," "an Old Woman," in the last line, it is most probable that the man is meant. A Man, torn by the bite of a savage Dog, threw a piece of bread, dipt in his blood, to the offender; a thing that he had heard was a remedy for the wound.

Then thus does the Cat with deceit and wicked malice, destroy the community so formed by accident. She mounts up to the nest of the Bird: Thence she wanders forth on tiptoe by night, and having filled herself and her offspring with food, she looks out all day long, pretending alarm.

Henry Thomas Riley

Fearing the downfall, the Eagle sits still in the branches; to avoid the attack of the spoiler, the Sow stirs not abroad. Why make a long story? They perished through hunger, with their young ones, and afforded the Cat and her kittens an ample repast. Silly credulity may take this as a proof how much evil a double-tongued man may often contrive. There is a certain set of busybodies at Rome, hurriedly running to and fro, busily engaged in idleness, out of breath about nothing at all, with much ado doing nothing, a trouble to themselves, and most annoying to others.

It is my object, by a true story, to reform this race, if indeed I can: Tiberius Caesar, when on his way to Naples, came to his country-seat at Misenum,[7] which, placed by the hand of Lucullus on the summit of the heights, beholds the Sicilian sea in the distance, and that of Etruria close at hand. Caesar takes notice of the fellow, and discerns his object.

Just as he is supposing that there is some extraordinary good fortune in store for him: Then, in a jesting tone, thus spoke the mighty majesty of the prince: Country-seat at Misenum —Ver. This villa was situate on Cape Misenum, a promontory of Campania, near Baiae and Cumae, so called from Misenus, the trumpeter of Aeneas, who was said to have been buried there.

The villa was originally built by C. Marius, and was bought by Cornelia, and then by Lucullus, who either rebuilt it or added extensively to it. Of the chamberlains —Ver. The "atrienses" were a superior class of the domestic slaves. It was their duty to take charge of the "atrium," or hall; to escort visitors or clients, and to explain to strangers all matters connected with the pictures, statues, and other decorations of the house.

Burmann suggests that this duty did not belong to the "atriensis," who would consequently think that his courteous politeness would on that account be still more pleasing to the Emperor. The "xystus" was a level piece of ground, in front of a portico, divided into flower-beds of various shapes by borders of box.

Much higher price —Ver. He alludes to the Roman mode of manumission, or setting the slaves at liberty. Before the master presented the slave to the Quaestor, to have the "vindicta," or lictor's rod, laid on him, he turned him round and gave him a blow on the face. In the word "veneunt," "sell," there is a reference to the purchase of their liberty by the slaves, which was often effected by means of their "peculium," or savings.

No one is sufficiently armed against the powerful; but if a wicked adviser joins them, nothing can withstand such a combination of violence and unscrupulousness. A Crow came through the air, and flying near, exclaimed: Induced by her words, the Eagle attends to her suggestion, and at the same time gives a large share of the banquet to her instructress. Thus she who had been protected by the bounty of nature, being an unequal match for the two, perished by an unhappy fate.

Whatever violence and unscrupulousness attack, comes.

Editorial Reviews. About the Author. CHRISTOPHER SMART holds degrees from Yale Buy The Comedies of Terence and THE FABLES OF PHÆDRUS By HENRY THOMAS RILEY, B.A.: Read Kindle Store The Comedies of Terence and THE FABLES OF PHÆDRUS By HENRY THOMAS RILEY, B.A. Kindle Edition. The comedies of Terence, translated by Henry Thomas Riley (, B.A. of the fables of Phaedrus: Riley's own, and those of Christopher Smart ().

Laden with burdens, two Mules were travelling along; the one was carrying baskets[13] with money, the other sacks distended with store of barley. Suddenly some Robbers rush from ambush upon them, and amid the slaughter[15] pierce the Mule with a sword, and carry off the money; the valueless barley they neglect. While, then, the one despoiled was bewailing their mishaps: Being used especially in the Roman treasury, the word in time came to signify the money itself. Hence our word "fiscal.

Born in June , he was only son of Henry Riley of Southwark , an ironmonger. He entered Trinity College, Cambridge , but at the end of his first term migrated to Clare College where he was admitted on 17 December , and elected a scholar on 24 January In he obtained a Latin essay prize. On 16 June he was incorporated at Exeter College, Oxford. Riley was called to the bar at the Inner Temple on 23 November , but early in life he began hack work for booksellers to make a living, by editing and translation.

On the creation of the Historical Manuscripts Commission by royal charter in April , Riley was engaged as an additional inspector for England, and given the task of examining the archives of various municipal corporations , the muniments of the colleges at Oxford and Cambridge, and the documents in the registries of various bishops and chapters. His Dictionary of Latin Quotations and , was included in the same series.

Albani, comprising the Annals of John Amundesham and , 2 vols. He also published in a volume entitled Memorials of London and London Life, a series of Extracts from the City Archives, — From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

- „Der gestörte Unterricht“ - Unterrichtsstörungen in der pädagogischen Theorie und Praxis (German Edition)

- The Man of the Forest Plus 26 Other Zane Grey Classic Westerns

- :The Wisdom of the Intenders: High Lights (The highest lights teachings Book 1)

- The Beauty of Self-Control

- Choices of the Chosen: Lessons from Israel’s Shepherd King