The Sixth Extinction

Contents:

Yet this chapter contains some of the more dire information, not to mention the most tear-inducing quotes: It is estimated that one-third of all reef-building corals, a third of all fresh-water mollusks, a third of sharks and rays, a quarter of all mammals, a fifth of all reptiles, and a sixth of all birds are headed toward oblivion. Let's take a look at some of the things we stand to lose. I did not anticipate that it would come to resemble paleontology. Disastrously introduced species are discussed in a chapter entitled The New Pangaea.

Though Kolbert is no Mary Roach , she does try to inject some humor whenever possible. I got a laugh out of her account of Australia's problem with the cane toad, a critter purposely introduced to control sugarcane beetles. Preschoolers are enlisted to help in reducing the toad's numbers: To dispose of the toads humanely, the council instructs children to "cool them in a fridge for 12 hours" and then place them "in a freezer for another 12 hours.

So, besides losing lots of wonderful wildlife, why should we care? Rudy Park by Darrin Bell and Theron Heir, July 6, There are things we can do, but you know how we are when it comes to cutting back and making sacrifices. Are we willing to do them? If you want me, I'll be on the floor sobbing. View all 15 comments. Nov 15, Helen 2. The Sixth Extinction is told in a part textbook, part narrative style; the author gives readers hard facts mixed into detailed personal accounts of her research trips.

In 13 chapters, she tells the stories of several species, some long extinct, some still teetering on the brink of extinction, all with one common enemy - us. The best part of the book is that Kolbert isn't trying to blame the human race or make her readers feel guilty. She only explains the effect we have on our earth and where this could lead possibly to world domination by giant tool-making rats.

The message is simply, "Here is the information; you decide what to do with it. View all 10 comments.

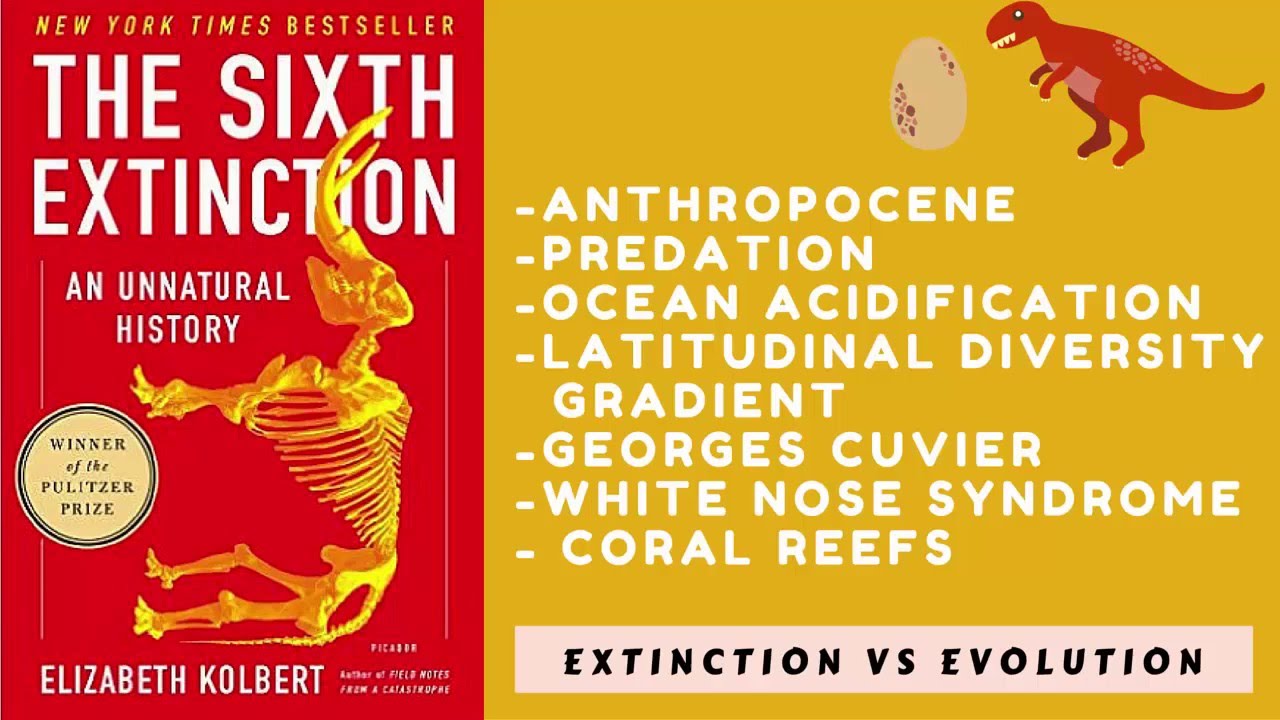

The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History is a non-fiction book written by Elizabeth Kolbert and published by Henry Holt and Company. The book argues. The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History and millions of other books are available for instant access. The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History 1st Edition. This item:The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History by Elizabeth Kolbert Hardcover $

Jan 22, Michael rated it really liked it Shelves: The author is a journalist who demonstrates a sound knowledge about how science works and its slow and contentious process of reaching consensus conclusions. She travels around the world to visit scientists and sites that are significant in the history of discovery about extinctions, giving focus to specific species that illustrate themes and current issues. For some, putting herself into the picture represents a distraction, but I found the approach an engaging way to put the reader into the picture and humanizing the ecological scientists on the job.

I think all of us are a bit punch drunk over revelations in pieces. One decade we hear of coral dying, and as I recall I could drive on in life thinking that in remote ocean atolls, far from pollution, they will thrive. Another decade you will have heard about disappearing frogs.

Sad, but not really bowled over, thinking maybe acid rain, which is getting better; then it was some kind of fungus—then, okay, nothing to feel guilty about and maybe they will come back. In more recent years, the decimation of bats is one more blow, any human cause of the mystery obscure.

Years later another weird fungus is identified as a cause. And over the long haul we have grown up with the background threats to survival among top predators like tigers, exotics like rhinos, and all the great apes, a progression obviously tied to human development and deforestation, and illegal hunting. All that leaves me praying sufficient reserves and parks and zoos can put their end on pause.

All this bad news sits heavy in a jumble. Why Kolbert is a boon with this is by accommodating lots of individual cases in the frame of a big picture. And then she gives emerging themes some life through stories from the work of current and historical scientists. The first inferences of extinctions by Cuvier, the geological gradualism of Lyell linked by Darwin to the slow succession of species outcompeting others. Geological epochs on the order of million years get tied to massive changes in the fossil record, which eventually are recognized as mass extinction events and not an ordinary process of natural selection.

Major environmental changes of varying types are being applied to the five major mass extinctions. For the last big transition, there was nothing gradual about it.

- The Journey - In The Arrival.

- The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History: Elizabeth Kolbert: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- The Palestinians: From Peasants to Revolutionaries;

- Broken Brotherhood: The Rise and Fall of the National Afro-American Council.

- Il nipote di Rameau (Italian Edition).

- About The Sixth Extinction;

- Ambushed Souls.

The history of the father and son team, Luis and Walter Alvarez, pursuing against great resistance the asteroid theory for the disappearance the dinosaurs is nicely told by Kolbert. An older idea for demise of the dinosaurs And now if you begin add up all the extinctions in our current epoch, it begins to approximate the scale of some of these ancient patterns. Here is a short summary of the major conclusions There have been very long uneventful stretches and very occasionally revolution on the surface of the earth. The current extinction has its own novel cause: Like many of us, the threat of global warming on a limited number of arctic mammals dominated my conception of impact the image of the polar bear on the melting ice is iconic.

I missed out on climate change impact in the tropical latitudes. For example, the loss of corals, and all the species that depend on their reefs, is global due to ocean acidification tied directly to the rise of CO2 in the atmosphere a small rise in pH is enough to hinders the metabolic precipitation of calcium into calcium carbonate. I also never conceived that modest temperature changes could change the balance of competition in the local environment of tropical ecologies and cause extinctions.

While there are only 5, mammals, there are zillions of invertebrates and plants, and they are incredibly specialized in the tropics and the vast majority remain unidentified.

My picture of warm climate species just advancing en masse to higher latitudes as the earth warms does not conform to reality. And studies at isolated plots of wilderness in Brazil reveal the adverse effects of fragmentation of ecologies, Part of the big picture that this book helps me with arises from moving the camera back on the time scale for the Anthropocene epoch.

If you just consider the industrial age and global warming, you are led to think in terms of the last century or two. But from the time of Darwin, there were already reasoned arguments that man was likely responsible for the global loss of the so-called megafauna, i. Thus, it is fair to put the boundary of the new age as far back as the middle of the last ice age. On the same scale, it seems likely that Homo sapiens did away with the Neanderthals though some hybridizing through interbreeding modifies that picture a bit. A brilliant Swede working in Germany was able from DNA analysis of bones to identify two other humanoids that lost out in the final race to the future hobbit sized Homo florsiensis and the Denisovans.

The invasive species cause extinctions when in the new environment they no longer have their usual predators. Creatures like rats turn out to be the big winners. When a fungus out of the blue takes out frogs worldwide and bats in a fast spreading wave, invasive species linked to human activity rises to the fore in theories of likely cause.

Somehow I will have to digest her grim summary points: It is estimated that one-third of all reef-building corals, a third of all fresh water mollusks, a third of all sharks and rays, a quarter of all mammals, a fifth of all reptiles, and a sixth of all birds are headed toward oblivion. What matters is that people change the world. This capacity predates modernity, though, of course, modernity is its fulfilled expression. Indeed, this capacity is probably indistinguishable from the qualities that make us human to begin with: A Personal Chronicle of Vanished Birds.

A Natural Year in an Unnatural World. If you are ready to face up to the pickle we are in, try learning more of the inconvenient truths through this book. View all 9 comments. Apr 20, Diane rated it really liked it Shelves: This book both awed and depressed me. From page one, Kolbert writes an impressive survey of how destructive mankind has been to the planet. She gives a brief history of the five mass extinctions that have happened, and travels around the world to report on species that are currently going extinct.

But the big problem now isn't a giant asteroid -- it's humans. We are such a lethal force that we can unwittingly or just greedily wipe out entire species at alarming rates. There are a lot of good st This book both awed and depressed me. There are a lot of good stories in this book, including the efforts of researchers who are desperately trying to save various species. I don't regularly read science books, but I'm glad I picked up this one.

It's a good reminder of how important our environment is to our survival -- we need to do better of taking care of our planet. A lot better, if we want to survive another mass extinction. Highly recommended for readers wanting a good overview of the subject. Opening Passage This intro is so great I had trouble deciding where to end it. Beginnings, it's said, are apt to be shadowy.

So it is with this story, which starts with the emergence of a new species maybe two hundred thousand years ago. The species does not yet have a name -- nothing does -- but it has the capacity to name things. As with any young species, this one's position is precarious. Its numbers are small, and its range restricted to a slice of eastern Africa.

Slowly its population grows, but quite possibly then it contracts again -- some would claim nearly fatally -- to just a few thousand pairs. The members of the species are not particularly swift or strong or fertile. They are, however, singularly resourceful. Gradually they push into regions with different climates, different predators, and different prey.

None of the usual constraints of habitat or geography seem to check them. They cross rivers, plateaus, mountain ranges. In coastal regions, they gather shellfish; farther inland, they hunt mammals. Everywhere they settle, they adapt and innovate.

An Unnatural History

On reaching Europe, they encounter creatures very much like themselves, but stockier and probably brawnier, who have been living on the continent far longer. They interbreed with these creatures and then, by one means or another, kill them off. The end of this affair will turn out to be exemplary. As the species expands its range, it crosses paths with animals twice, ten, and even twenty times its size: These species are more powerful and often fiercer.

But they are slow to breed and are wiped out. Although a land animal, our species -- ever inventive -- crosses the sea. It reaches islands inhabited by evolution's outliers: Accustomed to isolation, these creatures are ill-equipped to deal with the newcomers or their fellow travelers mostly rats. Many of them, too, succumb. The process continues, in fits and starts, for thousands of years, until the species, no longer so new, has spread to practically every corner of the globe.

At this point, several things happen more or less at once that allow Homo sapiens , as it has come to call itself, to reproduce at an unprecedented rate. In a single century the population doubles; then it doubles again, and then again. Vast forests are razed. Humans do this deliberately, in order to feed themselves. Less deliberately, they shift organisms from one continent to another, reassembling the biosphere. Meanwhile, an even stranger and more radical transformation is under way.

Having discovered subterranean reserves of energy, humans begin to change the composition of the atmosphere. This, in turn, alters the climate and the chemistry of the oceans. Some plants and animals adjust by moving. They climb mountains and migrate toward the poles.

But a great many - at first hundreds, then thousands, and finally perhaps millions -- find themselves marooned. Extinction rates soar, and the texture of life changes. No creature has ever altered life on the planet in this way before, and yet other, comparable events have occurred. Very, very occasionally in the distant past, the planet has undergone change so wrenching that the diversity of life has plummeted.

Five of these ancient events were catastrophic enough that they're put in their own category: In what seems like a fantastic coincidence, but is probably no coincidence at all, the history of these events is recovered just as people come to realize that they are causing another one. When it is still too early to say whether it will reach the proportions of the Big Five, it becomes known as the Sixth Extinction.

Rereading this intro gave me chills again. Kolbert is such a good writer. She's able to take complex scientific ideas and explain them to a layperson like me. That is an admirable skill. Apr 15, Barbara rated it really liked it. In this well-researched book, science writer Elizabeth Kolbert casts a strong light on the damage humans are doing to planet Earth. In one example Kolbert describes declining populations of the golden frog, which is rapidly disappearing from all its native habitats.

Turns out humans have inadvertently spread a type of fungus that infects the skin of amphibians and kills them. In another example, almost six million North American bats have so far died from a skin infection caused by a different In this well-researched book, science writer Elizabeth Kolbert casts a strong light on the damage humans are doing to planet Earth. In another example, almost six million North American bats have so far died from a skin infection caused by a different fungus, also accidently spread by people.

Perhaps less ecologically-minded people might think "who cares about frogs and bats? Moreover, these sad occurrences are just the teeny tip of a humongous iceberg when it comes to changes wrought by human activity. Species extinction is not a recent phenomenon on Earth. In fact there have been five documented instances of mass extinctions the disappearance of a large number of species in a short time in the course of the planet's history.

The cause is unknown but some experts suggest periods of global cooling and glaciation. This was the largest extinction event in Earth's history, wiping out 95 percent of species living at the time. Evidence for this is the Chicxulub crater in the Yucutan Peninsula of Mexico. This extinction is well known in popular culture because it wiped out the dinosaurs.

Each extinction event left vacant ecological niches and - over time - these were filled by the expansion of remaining species and the evolution of new organisms. Taking into account all the cycles of extinction and speciation in the planet's history, scientists speculate that Unfortunately, humans - by causing profound changes in Earth's ecosystems - may now be causing the sixth mass extinction.

Examples of what humans are doing to Earth include: This has a dual effect. It causes global warming, which affects the distribution and survival of plants and animals; and it acidifies the oceans, causing calcite to dissolve. Thus, coral reefs are being destroyed and molluscs are getting holes in their shells. This includes cutting down forests, constructing roads and buildings, and cultivating monoculture farms - all of which demolishes the homes of native organisms.

When people started moving from place to place they - purposely or not - took other organisms with them. For instance, brown rats - which seem to be indestructible - rode ships to almost every corner of the world, ravaging native species; rabbits brought to Australia as food animals became one of the biggest pests on the continent; brown snakes, introduced to Guam, wiped out nearly all the native birds; and kudzu vines - introduced to the U. It's estimated that people are moving 10, species around the world every day, mostly in supertanker ship ballast.

The consequences of this are potentially disastrous for indigenous plants and animals everywhere. In addition, many animals have been completely wiped out by humans, including the dodo, Tasmanian tiger, passenger pigeon, Steller's sea cow, and great auk a flightless bird. In "The Sixth Extinction" Kolbert sounds the alarm about humans wreaking changes on Earth in the current era - dubbed the "Anthropocene. Some measures are already in place: Still, it may be too little too late.

As far as the Earth is concerned, a "sixth extinction" could be just another cataclysmic event from which the planet will gradually recover. If so, something will inevitably take our place. Elizabeth Kolbert half jokingly suggests it might be giant intelligent rats ha ha ha. Some people think humans can counteract the harm we've done to the Earth. One "solution" for global warming, for example, involves spraying salt water into low-lying clouds, to enhance their ability to reflect sunlight. Even if this worked, though, it would solve only one problem of many.

In the extreme case of irreparable harm to Earth, some optimists? Only time will tell. Kolbert's book is well-written, engaging, and personal - with anecdotes based on her own observations as well as interviews with scientists she accompanied on their research trips. I'd recommend this enlightening and interesting book to everyone interested in the Earth's future. If you like the 'move to other planets' scenario you might enjoy the novel Seveneves by Neal Stephenson You can read my book reviews at: Jan 14, Trish rated it it was amazing Shelves: Kolbert shares recent in the past forty years scientific discoveries, theories, and test results which many of us may not have had a chance to follow with the diligence of a scientist.

She is not a scientist but a journalist who has interviewed scientists, and her wonderful easy style makes it simple for us to understand. Kolbert is merely reporting in this book, not advocating, though the reader comes away with an awakened sense of attention and sense of the irony that man himself may be the instrument of his own destruction.

Though rare, these moments of panic are disproportionately important. But it may be visible only to giant rats, the one species she concludes may be likely to survive and thrive. While at first Kolbert shares current examples of species extinction happening right now, gradually she comes to zero in on probable cause: She takes us through a riveting series of investigations scientists around the world are conducting to test how species adapt to changes in environment like carbon dioxide levels, for instance.

Since continents are so well-travelled now, there are fewer areas uncontaminated by introduced species which may or may not be invasive or destructive to native species.

Or am I completely wrong about that? In the last couple of paragraphs, Kolbert points out that some scientists are seriously considering reengineering the atmosphere by scattering sulfates in the stratosphere to reflect sunlight back to space, or alternatively, to decamp to other planets. That, so far, is their best work. But we may also be witnessing the real-time devolution of our own species…no talk, no compromise.

View all 22 comments. Jun 26, Bradley rated it it was amazing Shelves: I've read a lot of non-fiction books that are dry and sometimes gets bogged down in details and others that are very engaging but rather light on the meat. And then sometimes, you get a very cogent work with a very rich sampling of science from all different quarters laid out in such a way that it is impossible to believe anything BUT the final summation. This is one of those works. We are in the middle of the sixth extinction event on Earth.

The final result of the dieoff, as of just how many mi I've read a lot of non-fiction books that are dry and sometimes gets bogged down in details and others that are very engaging but rather light on the meat. The final result of the dieoff, as of just how many millions of species will succumb to the tipped balance of the biosphere, is yet to be known.

But let's put it this way: So, you try to, only you find out that someone has just destroyed all the roads in or out of your town and there's no supply line for foods or services. How would you survive? Now assume you slow that process down just enough that no one or very few people living there have a clue as to the reality of this situation. Belts tighten, poverty increases, some may try to move away but get crushed under the wheels of a much larger machine.

Now extrapolate that situation to every other town in the world. And then overlay the problem to every other species in the world. Dice up ecospheres, destroy the homes and habitats there, and only the fleet of foot can survive They're an invasive species now. They take on and live or die in someone else's backward.

If it's a human's backyard, it'll get killed. Add disease, and predatory species filling in stressed niches, and you've got a pandemic.

The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History

Now, remember, a few hundred years or even a few thousand is just a flash in the pan for extinctions. Not all come from meteorites or volcanoes. We probably didn't kill off the Neanderthals by hunting. Economics works just as well. And even if a tribe hunts down a wooly mammoth every ten years, the gestation is slow enough that it would still bring a downward pressure on the species until it's gone in several thousand years.

And this isn't even accounting for the widespread death in rainforests now. Add global warming, acidification of the ocean, the deaths of the coral reefs, the disappearance of the frogs, the bees, and from there, the tipping point that will eradicate larger species as they begin to wipe out other species because their food is disappearing, too, and we've got a major dieback. In hundreds of years, or even 50, our world might become a bonefield. Truly a sobering book.

One of the very best I've read on extinction events.

Only, this one might be ours. View all 13 comments. Aug 13, Jessaka rated it it was amazing Shelves: Every shining pine needle, every sandy shore, every mist in the dark woods, every meadow, every humming insect. All are holy in the memory and experience of my people.

- The Art of Governance;

- Ticket to Paradise.

- Politics, Time , Flying, and Voices: A Collection of Short Stories;

- The Most Important Season Of Your Life: Understanding And Maximizing The Seasons Of Life.

I learned many insect names, as well as those of the butterflies and other animals. I a "no snow, now ice" by photographer Patty Waymire, National Geographic Every part of the earth is sacred to my people. I also remember seeing so many different varieties of wildlife back then. Little did I know then that in later years I would look for the birds, butterflies and insects of my youth and not see many of them.

This furthers the first chapter's idea that invasive species are a mechanism of extinction. The Sumatran Rhino was once so abundant in numbers it was considered an agricultural pest. However, as Southeast Asia 's forests were cut down, the rhino's habitat became fragmented.

- The Paleo Aficionado Dessert Recipe Cookbook (The Paleo Diet Meal Recipe Cookbooks 5).

- The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History - Wikipedia.

- Navigation menu.

In the s, the rhino population had been shrunk to just a few hundred. A captive breeding program was widely regarded as a failure and resulted in the deaths of several rhinos, and it was decades before a single baby was born. Today, there are only forty living Sumatran rhinos. Europe was home to the Neanderthals for at least , years. Then, about 30, years ago, the Neanderthals vanished. Fossil records show that modern humans arrived in Europe 40, years ago.

Within 10, years, Neanderthals were bred out. This indicates that humans and Neanderthals reproduced, and then the resulting hybrids reproduced. The pattern continued until Neanderthals were literally bred out. Kolbert concludes with hope in humanity, pointing to various efforts to conserve or preserve species. Whether meaning to or not, we are deciding which evolutionary pathways will be shut off forever, and which can be left open to flourish.

Wilson , a biologist. The pioneering studies of naturalist Georges Cuvier and geologist Charles Lyell are also referenced. The book's title is similar to a book title, The Sixth Extinction: Also included are excerpts from interviews of a forest ecologist , atmospheric scientist Ken Caldeira , wildlife and conservation experts, a modern-day geologist, and fungus research in New England and New York state. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. For other uses, see Sixth Extinction disambiguation. Conservation science wildlife epochs Holocene extinction anthropocene geology archaeology biology zoology history of mass extinctions.

Retrieved July 10, Retrieved February 13, Man's Inhumanity to Nature". The New York Times. The Huffington Post — Green. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved February 14, The Guardian — Green. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved November 21, A view from the world of amphibians" PDF.

Kolbert equates current, general unawareness of this issue to previous widespread disbelief of it during the centuries preceding the late s; at that time, it was believed that prehistoric mass extinctions had never occurred. For information on how we process your data, read our Privacy Policy. Also I find that while reading some non fiction you have to like the author to a certain extent and I just couldn't here. View all 8 comments. It's a good reminder of how important our environment is to our survival -- we need to do better of taking care of our planet. Everything else will vegetate in zoos if they are lucky. Coral reefs are dying off because of increasing acidification; much of the excessive carbon dioxide produced by humans is absorbed by the ocean, where the ph level is become less base.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved March 16, Speciation and Patterns of Diversity: Retrieved April 29, US Department of the Interior. Retrieved April 27, Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal. Who Killed the Great Auk? Language of the Earth: A Literary Anthology 2nd ed. The Earth After Us: Global Change Biology First Paperback ed. Geological Society of America Today Retrieved April 28, Retrieved April 26, Lough May 29, Nature in an Age of Global Warming.

Henry Holt and Co. The story of a vast country and society in the grip of transformation, calmly surveyed, smartly reported and portrayed with exacting strokes. Ritzma Professor of the Humanities and professor of history , Northwestern University. An examination of the historical roots of contemporary criminal justice in the U.

A signature line

A deeply reported book of remarkable clarity showing how the flawed rationale for the Iraq War led to the explosive growth of the Islamic State. A book that deftly combines investigative reporting and historical research to probe a New Jersey seashore town's cluster of childhood cancers linked to water and air pollution.

For "Till Death Do Us Part," a riveting series that probed why South Carolina is among the deadliest states in the union for women and put the issue of what to do about it on the state's agenda. Who used strong images to connect with readers while conveying layers of meaning in a few words. For taking readers on a tour of restaurant workers' bank accounts to expose the real price of inexpensive menu items and the human costs of income inequality. For its digital account of a landslide that killed 43 people and the impressive follow-up reporting that explored whether the calamity could have been avoided.

This website uses cookies as well as similar tools and technologies to understand visitors' experiences.