The Three Little Dwarfs (with panel zoom)/n/t/t/t - Classics Illustrated Junior

Contents:

In order to be consistent with previous work Blanton et al. It has been shown by Shimasaku et al. Surface brightnesses and surface mass densities. Following Blanton et al. Because our sample is extremely large, errors arising from large-scale structure are expected to be small. In many cases we will be interested in trends in the distribution of the parameter y as a function of the parameter x for example, in the distribution of concentration or size as a function of stellar mass.

In such cases, we make the trends more visible by plotting the conditional distribution of y given x , i. The grey-scale indicates the fraction of galaxies in a given logarithmic mass or magnitude bin that fall into each age-indicator bin. The contours are separated by factors of 2 in population density. Here and in all subsequent contour plots, each contour represents a factor of 2 change in density. The main effect of transforming from luminosity to mass is to produce a more regular variation of the indices. Recall that the measurement error on the D n index is small, typically around 0.

Again, one sees a striking trend towards older stellar populations for galaxies with larger stellar masses. Histograms showing the fraction of galaxies as a function of D n in eight different ranges of stellar mass. The numbers in the upper right-hand corner of each panel list, from top to bottom, the fifth, 25th, 50th, 75th and 95th percentiles of the distribution. The number in the lower right-hand corner is the number of galaxies contributing to the histogram. This means that the fraction of low-mass galaxies that have experienced recent bursts is higher than that for high-mass galaxies, even when the two populations are compared at similar mean stellar age.

We illustrate this in detail in Fig. For comparison, we have overplotted different model galaxies with continuous star formation histories. The reader is referred to Paper I for more details concerning the models. Solar metallicity models are plotted in the right-hand panel. For low-mass galaxies, this is no longer true. As discussed in Paper I, many of these galaxies are likely to be experiencing a starburst at the present day. Symbols indicate the locus occupied by galaxies with continuous star formation histories.

In the left-hand panel, we have plotted 25 per cent solar models and in the right-hand panel we plot solar metallicity models. In Paper I, we introduced models in which galaxies formed stars in two different modes: In Paper I, we also introduced a method that allowed us to calculate the a posteriori likelihood distribution of F burst for each galaxy in our sample, given its observed absorption-line indices and the measurement errors on these indices. The distribution of the median value of F burst [which we denote as F burst 50 per cent ] for all galaxies in the given mass range is plotted as a solid histogram.

We define a subsample of high-confidence bursty galaxies as those objects with F burst 2. The distribution of F burst 50 per cent for this subsample is plotted as a dotted histogram in Fig. The solid histograms show the distributions of galaxies as a function of median value of the likelihood distribution of F burst in eight stellar mass ranges.

The dotted histograms show the distributions of the median value of F burst for the high-confidence bursty galaxies in each mass range. The fraction of galaxies that have experienced recent bursts decreases very strongly with increasing stellar mass. There are very few high-confidence bursty galaxies in our high-mass bins. Out of our entire sample of galaxies, we only pick out around galaxies with masses comparable to that of the Milky Way and with F burst 2.

For our full sample, the median value of the burst mass fraction correlates with stellar mass. The same is not true for the high-confidence bursty galaxies - these systems have burst mass fractions that are independent of stellar mass. Note that our requirement that a burst be detected at high confidence will, by definition, bias this subsample towards high-burst fractions.

Classics Illustrated Junior 52 of 77 : Three Little Dwarfs by William B. Jones Jr.

The trend in burst mass fraction for our full sample is in some sense expected, because it is well known that more massive galaxies have lower gas mass fractions and thus contain less fuel for star formation e. What about the influence of our adopted prior? The analysis in Paper I showed that decreasing the number of bursty galaxies in the model library resulted in lower estimated values of F burst 50 per cent.

Our standard prior assumes that the fraction of bursty galaxies is constant, in apparent contradiction with the results shown in Fig. Our choice of prior would therefore tend to weaken , rather than strengthen, any true decrease in F burst towards high masses. Paper I also demonstrated that the definition and inferred properties of our high-confidence subset of bursty galaxies in insensitive to the adopted prior.

For galaxies with high values of D n , the trend is reversed.

See a Problem?

The numbers listed in the panels indicate the number of objects in the bursty sample top and in the continuous sample bottom. The line in the bottom left-hand panel indicates the surface brightness completeness limit of the SDSS survey. The surface mass density exhibits a strikingly tight correlation with stellar mass. In contrast, the r -band surface brightness only increases by a factor of 4 as M r increases by 8 mag. Interestingly, this is also the stellar mass at which galaxies switch from low D n to high D n in Fig. The main spectroscopic survey is complete to surface brightnesses a magnitude fainter than this, so our results should not be biased by surface brightness selection effects.

Solid histograms show the fraction of galaxies as a function of the natural logarithm of the half-light radius in the z band [ R 50 z ] in eight different ranges of stellar mass. The median value of C for these systems is around 2. At larger masses, the distribution shifts to progressively higher concentrations.

In our highest-mass bin 90 per cent of galaxies have C index values larger than 2. Histograms showing the distribution of galaxies as a function of C index for eight different ranges of stellar mass. The numbers in each panel list, from top to bottom, the fifth, 25th, 50th, 75th and 95th percentiles of the distribution.

The numbers in each panel list, from top to bottom, the fifth, 25th, 50th, 75th and 95th percentiles of each distribution. We note that all structural parameters discussed in this section have been calculated within circular apertures. Because of seeing effects, R 50 z may be overestimated for galaxies with small angular sizes. We have split the galaxies in each stellar mass range into two equal samples according to redshift, and we have compared the size distribution of the nearby sample with that of the full sample.

This is illustrated in two of the panels of Fig. As can be seen, the effects appear to be quite small.

- ;

- ISOTEC, Sigma–Aldrich Corporation, Miami Township, Ohio EXPLOSION AT BIOCHEMICAL FACILITY: LIQUID NITRIC OXIDE RELEASE.

- GRE Test Prep Geometry Review Flashcards--GRE Study Guide Book 6 (Exambusters GRE Study Guide).

- Elphy Grey.

- Child Health Psychology.

In addition, we have checked the scalings using R 90 z and find that our conclusions remain unchanged. In the previous two subsections we showed that both the star formation histories and the structural parameters of galaxies depend strongly on stellar mass. This is illustrated in Fig. We note that this corresponds very well to the value of C recommended by Strateva et al. We attempt to address this question in Fig. Note that the C index is determined directly from the photometric data, independently of both stellar mass and surface mass density.

It also fits in well with numerous studies that have demonstrated a clear correlation between star formation rate and gas surface density for samples of spirals e. In the previous subsections, we demonstrated that there are strong correlations between the star formation histories, stellar masses and structural parameters of galaxies.

Again, the suppressed cooling at the centres of observed galaxy clusters may offer a clue to the mechanism responsible for this. This book is not yet featured on Listopia. There have been many studies of stellar populations and star formation histories that focus on galaxies of a particular Hubble type. At its peak, in , Classics Illustrated Junior's average monthly circulation was , It seems very probable that the assembly of bulge-dominated galaxies involved chaotic processes such as mergers or inhomogeneous, rapidly star-forming collapse, which, for most systems, must have completed well before the present day. We note that the sizes output by the current SDSS photometric pipeline have not been corrected for seeing effects Stoughton et al.

Here we provide a summary of our results. Low-mass galaxies have low surface mass densities and low concentrations. High-mass galaxies have high surface mass densities and high concentrations. Below the transition mass the median size of galaxies increases as M 0.

- Kerrigan in Copenhagen.

- .

- ;

- Passion en Australie (Harlequin Horizon) (French Edition);

The fraction of galaxies that have experienced recent starbursts decreases strongly with increasing stellar mass and increasing surface mass density. Galaxies less massive than this have low surface mass densities, low concentration indices typical of discs and young stellar populations. More massive galaxies have high surface mass densities, high concentration indices typical of bulges, and predominantly old stellar populations. The fact that for low-mass galaxies the shape and width of the size distributions in Fig.

We note that neither of these two studies addressed possible variations in the size distributions of disc galaxies as a function of luminosity or of mass. It is not obvious how the stellar mass of a galaxy should scale with the mass of its dark matter halo. This means that the stellar mass fraction must increase with halo mass. This difference is largest for the lower-mass objects and disappears for the most massive systems in our samples.

Classics Illustrated Junior 52 of 77 : 552 Three Little Dwarfs

Fitting to the dominant part of the population of late-type galaxies i. The star formation efficiency for disc galaxies apparently increases with halo mass. Such an increase is expected in a model where supernova feedback controls the dynamics of the interstellar medium e. However, because we do not have any information concerning the gas fractions of the galaxies in our sample, we cannot say whether the suppression of star formation occurs because gas is expelled from the galaxy and from its halo, as is often assumed in these models, or because the conversion of gas into stars is slowed in low-mass systems.

It is interesting that Tremonti et al. Clues as to why this is the case may come from recent Chandra and XMM observations, which show that cooling of gas to temperatures below 1 keV is suppressed at the centres of rich clusters, where the most massive ellipticals are located e. It seems very probable that the assembly of bulge-dominated galaxies involved chaotic processes such as mergers or inhomogeneous, rapidly star-forming collapse, which, for most systems, must have completed well before the present day.

Under these circumstances, it is not clear that our assumed scaling between galaxy radius and dark matter halo radius is valid. Even if the simple scaling laws were to apply, the halo sizes and surface densities relevant for early-type galaxies are probably to be defined at higher effective redshift than those relevant for late-type galaxies.

This may explain why early-type galaxies in Fig. The scatter in surface density and size is also smaller for early-type than for late-type galaxies, as is very evident in Fig. We note that the Lyman break galaxies LBGs at high redshift can plausibly be identified with the progenitors of early-type galaxies.

Return to Book Page.

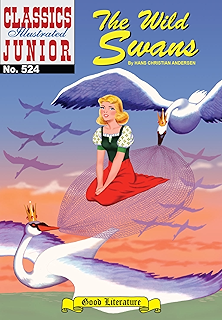

Classics Illustrated Junior 52 of Classics Illustrated Junior is a comic book series of seventy-seven fairy and folk tale, myth and legend comic book adaptations created by Albert Lewis Kanter as a spin-off of his flagship comic book line Classics Illustrated. Published by Famous Authors, Ltd.

The Gilberton Company, Inc.

The series' last original issue was The Runaway Dumpling, issue of The series ceased publication in Spring Published monthly, issues cost slightly more than other comic books of the time with a 15 cent cover price rather than the usual 10 or cents. Close to the end of publication in , prices jumped to cents. At its peak, in , Classics Illustrated Junior's average monthly circulation was , Issues included among their contents features such as comics adaptations of Aesop Fables usually two to three pages , a limerick by Edward Lear, a Mother Goose rhyme, or poem from Robert Louis Stevenson's A Child's Garden of Verses one page , and a one page factual article about a bird, beast, or reptile.

As the publisher allowed only in-house advertising in his books, the back cover interior sometimes offered a catalog of titles and a subscription order form. First editions included a "Coming Next Month" ad and a dot-to-dot puzzle on the inside front cover. The interior of the back cover featured a "Color this Picture with your Crayons" full-page line-drawn illustration of a scene from the tale.

The exterior of the back cover often depicted a full-page color illustration from the tale. Cole and Graham Ingels. Unlike other comic book publishers, Kanter reprinted his titles regularly and the line was distributed abroad. Paperback , 36 pages. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Classics Illustrated Junior 52 of 77 , please sign up. Be the first to ask a question about Classics Illustrated Junior 52 of Lists with This Book.