A History of the World in Twelve Maps

Contents:

Young hikers equipped only with mobile phones are, we read, a growing problem for mountain rescue teams.

A History of the World in Twelve Maps by Jerry Brotton: review - Telegraph

As for ordinary road maps, these have already been dispensed with in favour of satnav by idiots of all ages. Some might argue that a map viewed on a mobile phone is still a map, just as a Jane Austen novel read on a Kindle is still a novel — only the delivery mechanism has changed. But that is to miss the deep psychological change that is taking place in the age of Google Earth and GPS.

The new assumption is that any map — if it is a proper map — will be merely a sort of scientific record of what is there on the ground, as seen by a satellite and adjusted to a particular scale. The old idea of a map as a complex human artefact, with its own man-made conventions which may be quite different in different maps of the same place is fading away.

A History of the World in 12 Maps

If and when that idea disappears, we shall lose a significant element of our culture and its history. In a series of in-depth studies, starting with the Greco-Roman geographer Ptolemy and ending with — inevitably — Google Earth, it explores the ways in which some of the greatest mapping projects of the past have grown out of particular cultural and political circumstances.

The history of map-making, Brotton argues, is much more than a history of technical improvements; each of the 12 maps discussed here is, rather, an embodiment of human values. It is in fact one large calfskin. Simon Garfield on maps. Sale of the 17th century. Power, Propaganda and Art. Yet the narrative is not simply the one illustrative of western arrogance and greed articulated by Arno Peters. Mercator's projection, for instance, far from serving as a monument to the glories of European civilisation, was in fact an expression of the very opposite: His map, so Brotton convincingly demonstrates, "was part of a cosmography that aimed to transcend the theological persecution and division of sixteenth-century Europe.

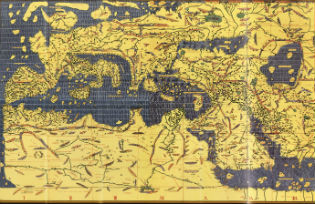

Nor are the subtlety and empathy that underlie this judgment absent when Brotton, venturing beyond his home territory of the Renaissance, comes to explore the cartographical expanses of the middle ages. His study of the delightfully named Book of Roger — a compilation of Greek, Latin and Arabic geographical knowledge assembled by a Muslim scholar under the aegis of a Christian king — provides a perspective on the limits of medieval multi-culturalism that is no less hard-headed for Brotton's sense of wonder that it should have existed at all.

Even more striking is his take on the tension between the dimensions of the eternal and the earthly implicit in the Mappa Mundi — which in its original setting pointed towards the second coming, that moment of cosmic transfiguration when the New Jerusalem will descend from heaven, and all geography promptly becomes redundant.

- ;

- !

- Anthropology - p. II (Italian Edition)?

- A History of the World in Twelve Maps - Jerry Brotton - Google Книги!

- .

- What a Wonderful World;

- !

This means, as Brotton wittily points out, that it belongs to "a genre of map unique in the history of cartography that eagerly anticipates and welcomes its own annihilation". Perhaps fittingly enough, it is only in the period that gave us the phrase "terra incognita" that his mapping of the contours of cartography in the past becomes just a trifle perfunctory.

Brotton's survey of Ptolemy and the reaches of classical geography that he was drawing on is workmanlike, but it lacks the spark and the sense of the unexpected that elsewhere are such features of the book. Readers who find the first chapter dry — as many may well do — are strongly urged not to cast the book aside, but to press on, and keep using it as a guide. Brotton's idea of tracing within maps the patterns of human thought and civilisation is a wonderful one.

History books Maps reviews. Order by newest oldest recommendations. Show 25 25 50 All. Threads collapsed expanded unthreaded. Loading comments… Trouble loading? It also has terrific map reproductions in black and white and vivid color. This weighty behemoth was a somewhat laborious, but a rewarding, interesting and enlightening read.

View all 3 comments. They are rich founts of information in text and picture form: They are an essential form of communication, but they are often overlooked. This is especially true now that Google and other companies have made it easy to explore the Earth virtually. As these tools become commonplace, the technology fades into the backgroun Maps are sexy. As these tools become commonplace, the technology fades into the background and becomes more like a pencil a piece of technology, but one so familiar as to be rather unremarkable than a supercomputer.

So it behoves us to stop and consider the staggering achievement that is mapping, particularly when so much of what we know stretches all the way back to a time before we had precise ways to measure time and space.

Buy A History of the World in 12 Maps on www.farmersmarketmusic.com ✓ FREE SHIPPING on I definitely feel like twelve maps alone is not enough to really delve into a full. A History of the World in Twelve Maps [Jerry Brotton] on www.farmersmarketmusic.com *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. History-of-the-World-in-Twelve-Maps.

Contrary to popular belief, the ancient Greeks figured out that the Earth was round pretty quickly. Jerry Brotton has written a history of the world, and he chose to do it through maps. Make no mistake, though: A History of the World in Twelve Maps is mostly about maps.

For the history component, he traces the social and scientific forces that influenced the production of the different maps he discusses. He links mapmaking to the search for knowledge as well as our desire to organize that knowledge. Finally, he explains how different maps served different purposes—some practical, some political, but all philosophical. Mapmaking is both a science and an art, but regardless of its classification, it is an ideological exercise.

One striking thing about this book is its remarkable evenness. I find that with non-fiction that takes a segmented approach like this, most books tend to be uneven: But every chapter is informative, interesting, and intriguing in its own way. Brotton has selected a good sample of maps throughout the ages. He begins each chapter by introducing the map or mapmaker before backtracking, explaining the historical context in which the map arose. We learn how the relationships between China, Japan, and Korea influenced the mapping of North Korea in the sixteenth century.

We learn how revolutionary France delayed the completion of the most ambitious survey project for its time, and property disputes in England resulted in British Africa and India being better-mapped than the UK.

As you might have gathered, there is a lot in this book. It was a good deal, considering that it comes with two sections full of colour plates of various maps. Brotton has obviously done the research which, much to my pleasure, he has meticulously documented in endnotes. The result is an information-dense look at history and mapmaking, and while this is never boring or dry, at times it is a little overwhelming. By covering so many topics, even with the depth and interest that Brotton displays, A History of the World in Twelve Maps becomes little more than a survey of world history.

Entire books can be and have been written about Ptolemy, or revolutionary France, or Mercator. If anything, this just means that I have a better idea of which books to seek out next In this respect, A History of the World in Twelve Maps reminds me a great deal of A Short History of Nearly Everything , a similarly sprawling survey of history through the lens of scientific discovery.

He communicates how polarizing the use of maps was in sixteenth century Europe, when Castile and Portugal were fighting over the rights to the entire world. He replicates the excitement that must have been palpable for those mapmakers involved in the surveying of eighteenth-century France. These days, maps are a commodity or a service —then, maps were a staggering achievement of science, art, and engineering. As a mathematician, I particularly enjoyed when Brotton mentioned the mathematics behind mapmaking. The Earth is round an oblate spheroid, to be pedantic about it , and it is not possible to project the curved surface of the Earth onto a 2-dimensional piece of paper with perfect fidelity.

You either get distorted areas or distorted angles or both , which means your map will look funny, or it will be useless for navigation, generally considered two very important aspects of a map. I remember talking about this back in my Philosophy of Science class days. Now, for those of you who have been reading this paragraph and are about to scramble wildly to cancel your Amazon order, wait!

There are no complicated equations in here, no mathematical sleights of hand. Brotton merely mentions the tricky and impressive math involved or highlights when some, like Mercator, deduce a projection without knowledge of the math involved. Of course, as with any survey-type book of history, there are things that Brotton left out that I would have liked to see. He laudably devotes a chapter to China and Korea, but the rest of the book is very much about the Western world. Absent is any discussion of Australian Aboriginal songlines or the mapping techniques of the indigenous peoples of the Americas.

Brotton describes attempts to map Africa but spends no time discussing how the indigenous inhabitants found their way around for tens of thousands of years. Even if that is the case, Brotton makes a passionate plea for a very open definition of a map in his introduction. The book is at its best when Brotton explains how the desires or aims of a government or an individual influenced the development and deployment of maps in that time period.

The premise, telling the history or selected parts of history through maps is quite cool. Brotton largely succeeds at what he sets out as his mission in the introduction. With amazing maps and enthusiastic explanations, Brotton educates and captivates. Jun 11, Simon Clark rated it really liked it Shelves: A wide-ranging, deftly told history of the world. The book ranges from the very earliest maps in the Babylonian world to modern geospatial applications such as Google Earth.

This book could have been complete drudgery in the hands of a lesser author, but Brotton creates a compelling narrative in each chapter, weaving a tapestry of many key threads through world history. And I really do mean world history - while Eurocentric, map-making in China, Korea, and the Americas is discussed, as well as t A wide-ranging, deftly told history of the world.

And I really do mean world history - while Eurocentric, map-making in China, Korea, and the Americas is discussed, as well as the impact of map-making on European colonialism and no, what you think about the Mercator projection is probably simplistic and wrong. The book is clearly well researched with lashings of references, and felt similar in tone to the also excellent Infinitesimal: How a Dangerous Mathematical Theory Shaped the Modern World by Amir Alexander - if you liked one of these books then you'll definitely enjoy the other.

It did drag a bit for the first third, but after that the book skips along nicely and is a compelling read.

Dec 17, Susanna - Censored by GoodReads rated it really liked it. A fascinating study of the history of maps, and of the concerns of the map-makers. For a further review: Dec 05, Alex rated it liked it Shelves: One of the disadvantages of having a kindle, is not knowing the actual size of a book. This was a huge and challenging one. There is a lot of information in this book and one learns some pretty interesting stuff. But it is also a very "dry" reading. Boring most of the time.

Search Tips

I had my share of "wows" - "wow, so this was how America appeared on the map" type of wows but that was it. A lot of dates and history facts which bored me to the core. In the end there are a lot of One of the disadvantages of having a kindle, is not knowing the actual size of a book. In the end there are a lot of fotos, all the maps discussed in the book are presented there. A black and white kindle is an unfortunate medium to see them.

A History of the World in Twelve Maps by Jerry Brotton: review

As I said, very informative. Nothing more nothing less. Jan 06, Ints rated it it was amazing Shelves: Dec 27, Nikki rated it it was ok Shelves: I was fascinated by the idea of this: A map covered in clearly-marked borders marks separations and national boundaries; different maps with disputed borders show areas of conflict. Maps can reveal belonging and isolation and the limits of the human imagination.

- Vanguards of the Plains A Romance of the Old Santa Fé Trail.

- Red Dog Rising.

- The Fanatical Gardener: and other stories.

- A History of the World in Twelve Maps by Jerry Brotton – review.

- The 90 Carat Diamond Theft (Hunter Burns Investigation, Book #5);

Or rather, he would pick maps and then talk about almost everything but the map: But the map itself, less so. Now, context is a great thing — hello, I was pretty much exclusively a new historicist as a literature postgrad — but I wanted more about the maps.

See a Problem?

More images would probably have helped, too. Originally posted on my blog. From the first known world map engraved on a cuneiform clay tablet to Google Earth's interactive three-dimensional image of the world, History of the World in Twelve Maps is a wonderful introduction to the history of cartography.

As the title suggests, Jerry Brotton picked twelve maps and placed them in their historical context, dedicating one chapter to each map. At first sight, his choice may seem arbitrary enough - why pick the Hereford map and not the Ebstorf map, or Pietro Vesconte's map, o From the first known world map engraved on a cuneiform clay tablet to Google Earth's interactive three-dimensional image of the world, History of the World in Twelve Maps is a wonderful introduction to the history of cartography. At first sight, his choice may seem arbitrary enough - why pick the Hereford map and not the Ebstorf map, or Pietro Vesconte's map, or Fra Mauro's Mappamundi?

Since the earth cannot be comprehensively mapped onto a flat surface, maps are necessarily a distortion of reality and, Brotton argues, shaped by the worldview of their makers. Each of the twelve chosen maps represents a worldview of a particular time in history and each of them has an interesting story to tell. Read this if you'd like to know why, in medieval times, maps by Islamic mapmakers tended to face south while Christian maps faced east and Chinese maps faced north which, incidentally, made the latter ones look surprisingly modern ; how Mercator was arrested and imprisoned for heresy and why his world map has been unfairly labelled as the ultimate symbol of Eurocentric imperial domination over the rest of the globe; or why Arno Peter's "equality map" was so highly criticised by the cartographic community and yet so popular with development aid organisations such as Oxfam and UNDP.

Brotton being a professor of Renaissance Studies, it is not surprising that his narrative comes most alive when describing the maps that were being made when Europeans started to explore entire continents that were previously unknown: These "Renaissance chapters" are really excellently done. Having worked with maps for most of my adult life, these Twelve Maps and the stories behind them weren't new to me, but some of the observations were.

Although Eratosthenes is generally thought of as the father of geography, Brotton pointed out that the description of the shield of Achilles fashioned by Hephaestus in Homer's Iliad is actually the first account of what we would now call geography: Moving out, the shield portrayed two fine cities of mortal men, one at peace, one at war; agricultural life showing the practice of ploughing, reaping and vintage; the pastoral world of straight-horned cattle, white-woolled sheep; and finally the mighty river of Ocean, running on the rim round the edge of the strong-built shield…", and this prompted me to read the Iliad again - a fine translation by Robert Graves.

All in all, this book is a fascinating overview of mapmaking throughout the history of humankind. Dec 11, Bellish rated it really liked it Shelves: This is not so much a history of the world in twelve maps as the stories of twelve maps and their places in history. The author's main premise is that maps are inherently subjective and are influenced by the culture that produces them and its motivations for that production. The premise is elegantly explored through twelve chapters, each with a single word title describing the main influence on the map's production.

Thus we see medieval mappae mundi that set out to describe the world with refere This is not so much a history of the world in twelve maps as the stories of twelve maps and their places in history. Thus we see medieval mappae mundi that set out to describe the world with reference to biblical details "Faith" , the assertion of a proud new dynasty in the Korean peninsula, overshadowed by its neighbour "Empire" , an exploration of the mapmaking of the Dutch East India Company "Money" , all the way up to Google Earth "Information".

It turns out that the history of cartography is not simply a tale of filling in the gaps, occasionally spiced up with a complicated treatise on a new projection. It is a discipline that has varied hugely in why it is done, who it is done by, and who it is done for. The strength of this book is that it doesn't shy away from technical details and in depth discussion of cultural and political forces in play during a given period, and the author makes this completely accessible.

- CATSKILLS

- Un amour incognito - Etranges prémonitions (Black Rose) (French Edition)

- Color Your Life (Daily Meditations For The Soul Book 9)

- THE TANK WAR MISSION [The Classic 1960s Man from W.A.R. Series]

- Robert Louis Stevenson: A Biography (Text Only Edition)

- Real Food All Year: Eating Seasonal Whole Foods for Optimal Health and All-Day Energy (The New Harbinger Whole-Body Healing Series)

- Les grottes de Gettysburg (French Edition)