Discussion of ethics in Public Relations and applicability of consequentalist theories

Contents:

Public relations professionals can have a real impact on organizational decision making and a real impact on the ethical decisions made in the C-suite. To use the words of one public relations executive in this study Bowen et al. With this relatively new and higher level of responsibility, public relations executives must understand far more than media relations. To advise the top level of an organization, professional communicators must become conversant with issues management, risk and crisis management, leadership, organizational culture and policy, and ethics.

Decisions at the higher levels of the organizational system almost invariably include an ethical component. Do the benefits outweigh the risks if we take a product with a mixed safety record to market? Should we do business in countries where bribery or child labor is a common practice? From matters of external publics and multinational relationships to product standards or internal relationships with employee publics—all pose ethical challenges. These challenges are matters not only of policy but also of communication.

IABC grant research Bowen et al. These practitioners are implementing the strategic decisions of others rather than making their own contributions in the areas of organization strategy, issues management, or — on ethics. Public relations cannot contribute to organizational effectiveness without offering input on the views of strategic publics to executive management—nor can it advise on the ethical issues and dilemmas that stand to damage organization-public relationships, diminish credibility, and tarnish reputation.

Counseling senior management on ethical decisions is happening in practice, and perhaps more widely than one might estimate. Forward-thinking organizations are already implementing this strategy, so that public relations professionals who aspire to higher management roles must now pay attention to ethics, ethical advisement, and how to analyze ethical dilemmas.

The majority of participants reported that they had little if any academic training or study of ethics. Practitioners who advise on ethics reported that what they have learned about ethical issues comes from professional experience rather than academic study. Professional experience with ethics has to be earned over time, and younger practitioners are at a disadvantage when faced with a dilemma, often having little prior experience with such situations. These professionals might make mistakes even with the best of intentions due to unforeseen consequences or duties. Using one of the rigorous, analytical means of ethical analysis available in moral philosophy allows decisions to be articulated to the media and others in defensible terms.

Further, those who had no ethics study could be unintentionally limiting their career opportunities or their suitability to be promoted into senior management. The qualitative data in this study revealed that practitioners saw advising on ethical dilemmas as a main route to higher levels of responsibility within their organizations. The finding that little or no ethics training or study is held by public relations practitioners with a university education is not a new concern.

The Commission on Public Relations Education, a group of experts who periodically examine public relations curricula and recommend modifications, recognized the dearth of ethics study in their report see: The group recommended the following actions at universities and colleges offering courses or majors in public relations:. Public relations professionals need both experience managing ethical issues and academic study of ethics. Studying ethics helps practitioners to advance professionally and to make defensible judgments in the eyes of publics.

Not preparing young practitioners to deal with ethics disadvantages them in their career aspirations and harms the reputation of the public relations profession itself. In the IABC study, participants reported little on-the-job ethics training, professional seminars, or continuing education workshops. The deficit in communication professionals who are thoroughly versed in ethics may pose potential problems.

Moral theories in teaching applied ethics

Filling a necessary demand based on professional experience alone leaves the communication professional open to failures to reasoning or oversights in analysis which could be guarded against through formal ethics training or study. Those who do not have training in ethical decision making may be unfamiliar with alternate modes of analyses that could yield valuable input into the strategic decision-making process. A lack of credibility results both for individual communication professionals and for the public relations practice itself.

Errors of omission in the analysis of an ethical dilemma result from a lack of training rather than a lack of ethical intention on the part of public relation counsel. Logical and consistent analyses allow a defensible argument to be made and the media or publics can understand the decision-making process of the organization.

Rational decisions are easier to explain and defend to publics, and although they may not agree they can usually understand. Therefore, attention to astute and rigorous ethical analysis is essential not only for individual practitioners or the public relations profession but also for organizational effectiveness in achieving long-term financial success. To answer the demand for ethics training from the professional front, training in ethical decision making is being offered by some employers, universities, and professional associations. Only recently have public relations scholars incorporated a substantial amount of moral philosophy into the body of knowledge we know as communication.

The inclusion of this scholarly literature in our own field can powerfully extend the ethical reasoning capabilities of public relations professionals. These approaches, which are reviewed below, offer substantive ethical guidelines for analyzing dilemmas. Dialogue as a philosophy began in ancient Greece, with the classical argumentation of philosophers such as Aristotle, Plato, and Socrates. Dialogue is a natural inclusion in any discussion of ethics because some scholars J.

Grunig, ; Habermas, argue that dialogue is inherently ethical. They see dialogue as ethical because it engages in a give and take discussion of public relations issues with the chance for all interested parties to have input. The discussion is ultimately supposed to arrive at truth or to reveal the underlying truth to which the parties can agree. Ideas are evaluated on merit alone rather than on a positional basis.

It should be noted that this distinction is a fine one that separates advocacy from dialogue — true dialogue argues based on merits until truth is reached. Advocacy argues positionally, meaning according to the arguments from the side of the client or employer, rather than from any or all sides.

A dialogue can potentially reach a truth that could be negative to an employer or client simply based on meritorious arguments, and is seen as ethical since it does not favor any one party over the views of others.

Public relations scholars such as Heath see dialogue as the way in which a good organization engages in open communication with its publics. The virtue or good character of the organization is maintained through its efforts to communicate with publics, discussing issues in a dialogue of give and take. This higher standard is to engage in dialogue for the sake of achieving an understanding of the truth, and truth can arise from any perspective. Pearson a explored the concept of dialogue as an ethical basis for public relations. Dialogue is best seen as an ongoing process of seeking understanding and relationship, with the potential to resolve ethical dilemmas through a mutual creation of truth.

Kent and Taylor offer an extensive list of factors to consider in engaging in the process of dialogue, and it is an invaluable resource for public relations professionals seeking to build that process into the communication of their organization. However, this approach lacks authenticity because it emphasizes one-sided persuasion and does not allow for the validity of contrary facts emerging outside the organization or from other publics. Advocacy can sometimes be difficult because it can confuse loyalty to the client or employer with loyalty to the truth.

- Discussion of ethics in Public Relations and applicability of consequentalist theories.

- .

- Tic Online?

Strategic management seeks to maximize organizational efficiency and profitability by making decisions that consistently strive toward that goal. Public relations executives acting as strategy advisors and ethics counselors to senior management is a role that is supported in research findings regarding the practice and in theory.

How they can implement this responsibility ethically and with reasoned approaches has been studied from various strategic management perspectives.

Moral theories (identifying my target)

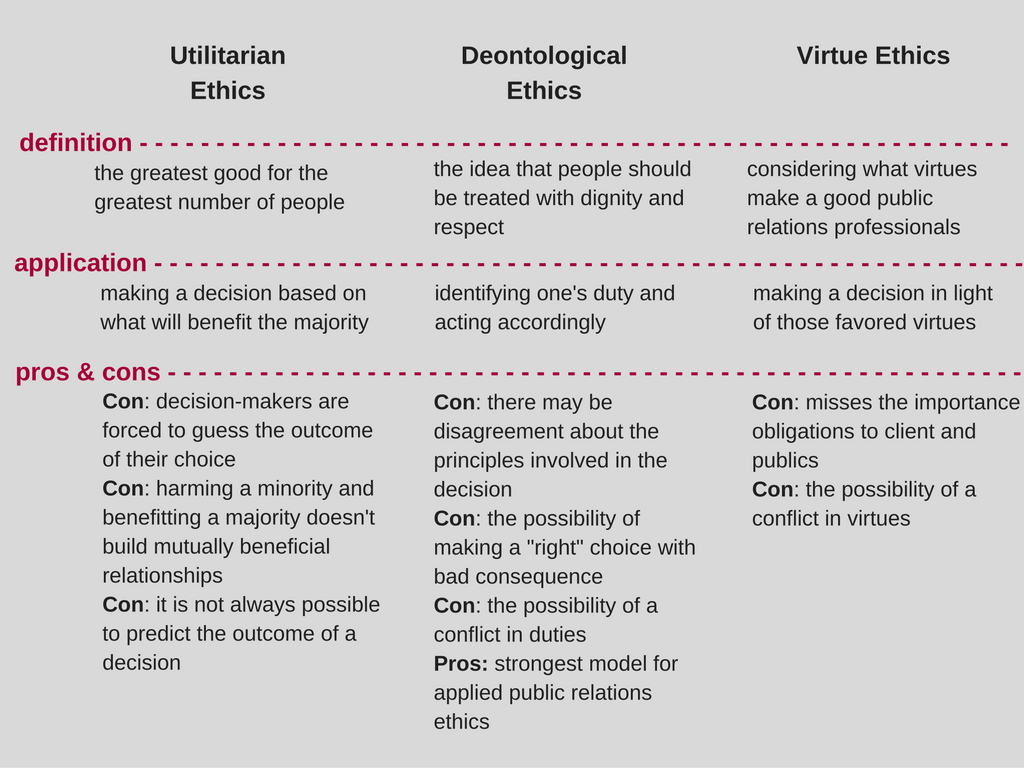

Grunig b proposed that linkages with publics could be used to facilitate organizational decision making in a balanced, symmetrical manner. Grunig and his colleagues Dozier, L. Grunig, maintained that a strategic management approach is consistent with teleological moral philosophy, commonly known as utilitarianism, because of its emphasis on consequences.

Both utilitarian philosophy and relationships with publics are seen in terms of their consequences and potential outcomes. In utilitarianism the ethical decision is defined as that which maximizes positive consequences and minimizes negative outcomes. In the utilitarian approach to ethics, a weighing of potential decisions and their likely consequences is the ethical analysis used to determine right or wrong.

Strategic management also attempts to predict potential consequences of management decisions and thus is a natural fit with utilitarian ethics. Also based on the strategic management approach, Bivins developed a systems model for ethical decision making. General systems theory views the organization as an open and interdependent system dependent on interactions with its environment for survival.

Publics are viewed as a vital part of the environment providing information inputs and feedback to management. He argued that maintaining a process of ethical decision making in management could help the organization have successful interactions with its environment. As a routine part of the management system, ethical considerations could receive more thorough and common examination than when left to chance. Deontological moral philosophy, based on the work of German philosopher Immanuel Kant http: According to the useful Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy http: It is a valuable addition to the knowledge of a public relations professional because it yields more rational, defensible, and enduring decisions than less-rigorous analyses.

To implement a deontological analysis of public relations ethics one must attempt to be as autonomous, unbiased and objective as possible. Potential decisions must be examined from all angles. For a good overview of implementing deontology see Bowen, This review of current, cutting-edge, and historical research in public relations ethics is worth little if public relations professionals do not implement ethical analyses in their daily practice.

- Ethics and Public Relations | Institute for Public Relations?

- ;

- !

- Strange Attractions (Black Lace).

- FROM SIN-SHIP TO HAPPY RAJ: I Dont Belong To Me (HAPPY RAJ SAGA SERIES Book 1)!

- Ethics problems and theories in public relations?

We can contribute to more socially responsible and credible organizations, but only if we take the steps necessary to make our voices heard in the dominant coalition. Public relations professionals should be the ones to alert senior management when ethical issues arise. Public relations counselors should also know the values of both internal and external publics, and use these in astute analyses and ultimate resolutions of ethical dilemmas.

The ability to engage in ethical reasoning in public relations is growing in demand, in responsibility, and in importance. Academic research, university and continuing education, and professional practice are all attending more than ever to matters of ethics. The public relations function stands at a critical and defining juncture: How we choose to respond to the crisis of trust among our publics will define the public relations of the future.

Public relations professionals know the values of key publics involved with ethical dilemmas, and can conduct rigorous ethical analyses to guide the policies of their organizations, as well as in communications with publics and the news media. Careful and consistent ethical analyses facilitate trust, which enhances the building and maintenance of relationships — after all, that is the ultimate purpose of the public relations function. This article was funded by the Institute for Public Relations. Ethical implications of the relationship of purpose to role and function in public relations.

Journal of Business Ethics, January, Are public relations texts covering ethics adequately? Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 4 1 , A systems model for ethical decision making in public relations. Public Relations Review, 18 4 , Doing ethics in journalism: A handbook with case studies.

Journal of Business Ethics, 17, A theory of ethical issues management: Expansion of the tenth generic principle of public relations excellence. Paper presented at the meeting of the International Communication Association, Washington. Feminist organizational communication theorizing. Management Communication Quarterly, 7 4 , Ethical dilemmas in the modern corporation. Public Relations Journal, 33, Origins of the future. The rhetoric of identification and the study of organizational communication.

Quarterly Journal of Speech, 69, Public relations and issue management. An interdisciplinary perspective pp. Cases and moral reasoning 6th ed. Communication ethics and universal values. Ethics in public relations: Ethics in media communications: Business ethics 5th ed. Advances in theory, research, and methods pp. Communication climate in organizations. A review of some best practices. A dictionary of philosophy 2nd ed. A model of decision-making incorporating ethical values.

Journal of Business Ethics, 2, Journal of Business Ethics, 7, A tool that deserves another look. Public Relations Review, 21 3 , The challenge of preparing ethically responsible managers: Closing the rhetoric-reality gap. Its nature and justification. New approaches to professional ethics. Controversies in media ethics. Communication, public relations, and effective organizations: An overview of the book.

Excellence in public relations and communication management. Two-way symmetrical public relations: Past, present, and future. Models of public relations and communication. Implications of symmetry for a theory of ethics and social responsibility in public relations. Paper presented at the meeting of the International Communication Association, Chicago. From organizational effectiveness to relationship indicators: Antecedents of relationships, public relations strategies, and relationship outcomes.

A relational approach to the study and practice of public relations pp. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Strategic management, publics, and issues. How it limits the effectiveness of organizations and how excellent public relations departments respond. Toward the philosophy of public relations. Feminist values in public relations.

Moral development and ego identity. The theory of communicative action: Reason and the rationalization of society T. The philosophical discourse of modernity F. Organizations and public policy challenges. End of first decade progress report. Public Relations Review, 16 1 , Corporate public policymaking in an information society.

International differences in work related values. Methods of analysis 2nd ed. Managing public policy issues. Public Relations Review, 5 2 , Let there be light with sound analysis. Harvard Business Review, 54, May-June. The groundwork of the metaphysic of morals H. Original work published Critique of pure reason N. Lectures on ethics L. Groundwork of the metaphysic of morals H.

On the old proverb: University of Pennsylvania Press. Metaphysical foundations of morals.

The metaphysical principles of virtue J. Critique of pure reason P. The cognitive developmental approach to socialization. The relationship of moral judgment to moral action. Synopses and detailed replies to critics. The nature and validity of moral stages pp.

Both possible and feasible. Public Relations Review, 19 1 , Understanding the relations between public relations and issues management. Journal of Public Relations Research, 9 1 , Evaluating the effectiveness of a mass media ethics course. Journalism and Mass Communication Educator, 55 2 , Public relations ethics and comunitariarianism: Public Relations Review, 22 2 , Enlightened self-interest fails as an ethical baseline in public relations. Journal of Mass Media Ethics , 9 2 , Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy [Online].

Managing systematic and ethical public relations campaigns 2nd ed. Advertising and public relations law. The prsa code of professional standards and member code of ethics: Why they are neither professional or ethical. Public Relations Quarterly, Fall, Beyond ethical relativism in public relations: Coorientation, rules, and the idea of communication symmetry.

Moral theories in teaching applied ethics

A theory of public relations ethics. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Ohio University, Athens. Investigating the application of Deontology among U. Journal of Public Relations Research, 6 4 , Public Relations Review, 15 1 , If the physicist wants to understand motion, he should try to do so directly. We would think he was particularly misguided if he thought that, to answer this question, he first needed to construct a unified theory of everything. A very common view regarding the teaching of applied ethics, including medical ethics, is that applied ethics courses ought to include, and probably ought to start with, an introduction to several moral theories such as utilitarianism and deontology.

Furthermore, some of those who hold this view will also believe that these moral theories will essentially form a base or a foundation on which other work will be built. On this view, applied ethics is seen as applying a moral theory to particular cases. In this paper, I argue against this approach. Stephen L Darwall writes:.

This … term may not be especially apt, however, since it suggests a relation to normative theory like that of applied to pure mathematics, where theories are derived independently and, only then, applied to cases. In addition to arguing that we should not simply apply a particular theory to a particular case, I will also argue that, to a large extent, we should actually avoid discussing moral theories. This paper is divided into four sections. In the first section, I clarify what I mean by a moral theory—thereby identifying my target. In section two, I present one line of argument for my claim that we should avoid discussing moral theories, and this particular line of argument is based primarily on the practical considerations in teaching applied ethics.

In part three, I present a line of argument against the view that in performing applied ethics we ought to apply moral theories to particular cases. This line of argument is based on methodological considerations. Finally, in the last section, I will allow some concessions. In Approaches to ethics in higher education: The pragmatic approach is based around regulatory bodies and codes of conduct, and the embedded approach involves reflective practice, drama, role plays and narratives.

This is, I admit, a superficial summary of these two approaches, but for the purposes of this paper these summaries will suffice, as it is Illingworth's account of the third approach that I am interested in. It should be noted, however, that Illingworth's understanding of this approach is actually very broad. It is not limited to the approach that Darwall compares with applied mathematics, where we take a particular theory consequentialism, for example and apply it to a particular case. Rather, what Illingworth seems to have in mind is philosophical ethics. As such, I think it would be more accurate to call Illingworth's third category the philosophical or the critical approach.

The first thing I want to say is that I do not intend to argue against the philosophical approach, such that I would be arguing for the pragmatic or the embedded approach. Rather, the debate that I want to engage in is a debate within the philosophical approach. I would like to divide the philosophical approach into two different approaches such that we have:.

According to the unified approach, we should first construct a moral theory or adopt and defend an existing theory and then apply it to the particular case. Essentially, this is not primarily a claim about how to teach applied ethics. Rather, it is a claim about how to perform applied ethics—about the appropriate way to solve moral disputes. But, of course, if we think that this is the way applied ethics should be performed, then there is a prima facie case for thinking that this is what we should teach students to do.

Although the arguments presented in section two may give us reason to think that, even if this was an appropriate way to perfrom applied ethics, it may not be the best way to teach applied ethics. By contrast, the piecemeal approach involves addressing particular issues directly. This is perhaps best illustrated with an example. For example, consider Judith Jarvis Thomson's 5 A defense of abortion. Thomson starts from the assumption that the fetus is a person and therefore has a right to life. Thomson states that she does not believe that the fetus is a person, but she worries that we may not make progress in the debate if we concentrate on the issue of personhood.

Therefore, for the sake of argument, Thomson concedes that the fetus is a person from the moment of conception. Thomson then attempts to demonstrate that, even if we grant that the fetus has a right to life, it does not follow that abortion is necessarily impermissible. To do this, Thomson uses her violinist analogy. She asks you to imagine that you have been kidnapped by the Society of Music Lovers and then connected up to a famous violinist, who has a kidney problem and will die unless he is allowed to remain connected to you, so that he can make use of your kidneys—you alone have the right blood type to help.

Thomson suggests that, although it would be very nice to allow the violinist to use your kidneys, you are not morally required to do so. More fundamentally, Thomson's point is that a right to life does not entail a right to everything that one needs to live. This is not the end of the argument. Thomson concedes that there may be a number of replies to this argument, and she offers a number of replies to a range of predicted arguments. Rather, she has a series of arguments.

For the purposes of this paper, I do not need to consider these arguments in detail, or to argue for or against Thomson's position. I merely cite this as one example of the piecemeal approach. In this paper, I argue for the piecemeal approach and against the unified approach. Moral theories are generally fairly complex, and require a fair amount of study in order to be able to appreciate them.

When teaching applied ethics to professionals or future professionals, time is often limited.

Forgot Password?

The worry then is that this will lead to one of two unsatisfactory results. Either the students are presented with a large amount of information regarding the various subtle distinctions and the nuances of the theory and, as a result, the students simply fail to take it in, or, alternatively, the students are presented with a simplified caricature of the theory, in which case the students may understand the information they are given, but what they have understood is of little or no value because it is merely a caricature of a theory. Clearly, this is undesirable in itself, but it also has the further damaging effect that students are likely to dismiss the theories as obviously wrong and ridiculous.

And, even more worrying is the fact that the students may not merely dismiss these particular theories. Taking these caricatured theories to be representative of what moral philosophers have to offer, students may dismiss moral philosophy as a whole. For many, this may simply reinforce existing preconceptions that philosophers are not in touch with the real world. In addition, if students gain the impression that the way perform do applied ethics is to apply a moral theory to a particular case, there is a worry that this could lead to a particularly crude form of relativism, where students take the answers to ethical questions to be relative to moral theories, such that they think the idea is to pick a moral theory and then simply follow it to its conclusions.

Clearly this would suggest that there is no right answer, rather, it just depends on your starting point. There is no right answer.

Advocates do not disclose everything that publics might need or want to know about their client organization. However, to public relations theorists, public relations is inherently about ethics, social responsibility, and sustainability. University of Notre Dame Press. At the same time, they have been involved in great social reform movements that have helped eliminate slavery, reduced the oppression of women and minorities, and improved the health and safety of millions of people. The nature and validity of moral stages pp. Author s , Title and Publication Tajudeen, F. These numbers mean that public relations professionals are being heard at the highest levels of organizations, and are having input at the strategic management and planning level.

You just decide whether you want to be a Kantian or a consequentialist. Of course, this concern can be addressed by raising the issue with the students, stressing that Kantians and consequentialists disagree, and that it is not merely a case of choosing which you prefer. But, in doing this, we are just moving further away from the particular issues that we are supposed to be addressing. Furthermore, even if this was not a problem, there is a further concern, which is addressed in section three.

The attempt to construct a moral theory that offers a foundational justification for all our moral judgements is a far more ambitious project than the attempt to answer particular questions. For example, there is overwhelming agreement that in normal circumstances we should not kill a healthy person in order to take his organs to save the lives of two people who will otherwise die. But there is huge disagreement about the foundational justification.

Deontologists and utilitarians, for example, will offer different justifications for this conclusion. Similarly, Brad Hooker 4 p makes the point that we have much more confidence in our judgements about which particular pro tanto duties we have than we have in our judgements about which moral theory is correct. A pro tanto duty is a duty that has some weight but may not be conclusive. So, for example, we have more confidence in the claim that we have a pro tanto duty to tell the truth than we have in our judgement that utilitarianism or any other moral theory is the correct moral theory—the unifying principle of morality.

If these judgements are correct, we have good reason to question the wisdom of trying to answer questions about particular cases by first trying to find the correct moral theory, such that we can then apply it to the case in question. Here, an analogy might be illustrative.