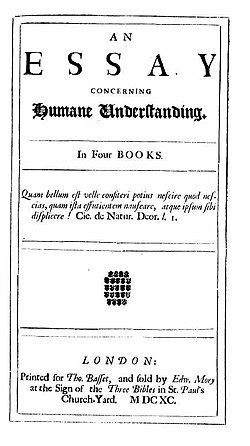

Understanding John Lockes Essay Concerning Human Understanding

Contents:

In the making of the names of substances there is a period of discovery as the abstract general idea is put together e. Language itself is viewed as an instrument for carrying out the mainly prosaic purposes and practices of every day life. Ordinary people are the chief makers of language. Vulgar Notions suit vulgar Discourses; and both though confused enough, yet serve pretty well for the Market and the Wake. Merchants and Lovers, Cooks and Taylors, have Words wherewith to dispatch their ordinary affairs; and so, I think, might Philosophers and Disputants too, if they had a mind to understand and to be clearly understood.

These ordinary people use a few apparent qualities, mainly ideas of secondary qualities to make ideas and words that will serve their purposes. Scientists are seeking to find the necessary connections between properties. A whale is not a fish, as it turns out, but a mammal. There is a characteristic group of qualities which fish have which whales do not have. There is a characteristic group of qualities which mammals have which whales also have. To classify a whale as a fish therefore is a mistake.

Similarly, we might make an idea of gold that only included being a soft metal and gold color. But the product of such work is open to criticism, either on the grounds that it does not conform to already current usage, or that it inadequately represents the archetypes that it is supposed to copy in the world. We engage in such criticism in order to improve human understanding of the material world and thus the human condition. In becoming more accurate the nominal essence is converging on the real essence. In contrast with substances modes are dependent existences—they can be thought of as the ordering of substances.

These are technical terms for Locke, so we should see how they are defined. First, Modes I call such complex Ideas , which however compounded, contain not in themselves the supposition of subsisting by themselves; such are the words signified by the Words Triangle, Gratitude, Murther, etc. Of these Modes , there are two sorts, which deserve distinct consideration. First, there are some that are only variations, or different combinations of the same simple Idea , without the mixture of any other, as a dozen or score; which are nothing but the ideas of so many distinct unities being added together, and these I call simple Modes , as being contained within the bounds of one simple Idea.

Secondly, There are others, compounded of Ideas of several kinds, put together to make one complex one; v. Beauty , consisting of a certain combination of Colour and Figure, causing Delight to the Beholder; Theft , which being the concealed change of the Possession of any thing, without the consent of the Proprietor, contains, as is visible, a combination of several Ideas of several kinds; and these I call Mixed Modes. When we make ideas of modes, the mind is again active, but the archetype is in our mind.

The question becomes whether things in the world fit our ideas, and not whether our ideas correspond to the nature of things in the world. Our ideas are adequate. If we find that someone does not fit this definition, this does not reflect badly on our definition, it simply means that that individual does not belong to the class of bachelors. Modes give us the ideas of mathematics, of morality, of religion and politics and indeed of human conventions in general.

Since these modal ideas are not only made by us but serve as standards that things in the world either fit or do not fit and thus belong or do not belong to that sort, ideas of modes are clear and distinct, adequate and complete. Thus in modes, we get the real and nominal essences combined. One can give precise definitions of mathematical terms that is, give necessary and sufficient conditions and one can give deductive demonstrations of mathematical truths.

Locke sometimes says that morality too is capable of deductive demonstration. Though pressed by his friend William Molyneux to produce such a demonstrative morality, Locke never did so. The terms of political discourse also have some of the same modal features for Locke. When Locke defines the states of nature, slavery and war in the Second Treatise of Government , for example, we are presumably getting precise modal definitions from which one can deduce consequences.

It is possible, however, that with politics we are getting a study which requires both experience as well as the deductive modal aspect. In the fourth book of An Essay Concerning Human Understanding Locke tells us what knowledge is and what humans can know and what they cannot not simply what they do and do not happen to know. This definition of knowledge contrasts with the Cartesian definition of knowledge as any ideas that are clear and distinct. What about knowing the real existence of things? Locke, for example, makes transdictive inferences about atoms where Berkeley is unwilling to allow that such inferences are legitimate.

This implies that Locke has a semantics that allows him to talk about the unexperienced causes of experience such as atoms where Berkeley cannot. What then can we know and with what degree of certainty? We can know that God exists with the second highest degree of assurance, that of demonstration.

We also know that we exist with the highest degree of certainty. The truths of morality and mathematics we can know with certainty as well, because these are modal ideas whose adequacy is guaranteed by the fact that we make such ideas as ideal models which other things must fit, rather than trying to copy some external archetype which we can only grasp inadequately.

On the other hand, our efforts to grasp the nature of external objects is limited largely to the connection between their apparent qualities. The real essence of elephants and gold is hidden from us: Our knowledge of material things is probabilistic and thus opinion rather than knowledge. We do have sensitive knowledge of external objects, which is limited to things we are presently experiencing.

While Locke holds that we only have knowledge of a limited number of things, he thinks we can judge the truth or falsity of many propositions in addition to those we can legitimately claim to know. This brings us to a discussion of probability. Knowledge involves the seeing of the agreement or disagreement of our ideas.

What then is probability and how does it relate to knowledge? So, apart from the few important things that we can know for certain, e. What then is probability? As Demonstration is the shewing of the agreement or disagreement of two Ideas, by the intervention of one or more Proofs, which have a constant, immutable, and visible connexion one with another: Probable reasoning, on this account, is an argument, similar in certain ways to the demonstrative reasoning that produces knowledge but different also in certain crucial respects. It is an argument that provides evidence that leads the mind to judge a proposition true or false but without a guarantee that the judgment is correct.

This kind of probable judgment comes in degrees, ranging from near demonstrations and certainty to unlikeliness and improbability in the vicinity of impossibility. It is correlated with degrees of assent ranging from full assurance down to conjecture, doubt and distrust. The new science of mathematical probability had come into being on the continent just around the time that Locke was writing the Essay. His account of probability, however, shows little or no awareness of mathematical probability.

Rather it reflects an older tradition that treated testimony as probable reasoning. Thus, when Locke comes to describe the grounds for probability he cites the conformity of the proposition to our knowledge, observation and experience, and the testimony of others who are reporting their observation and experience. Concerning the latter we must consider the number of witnesses, their integrity, their skill in observation, counter testimony and so on.

In judging rationally how much to assent to a probable proposition, these are the relevant considerations that the mind should review. We should, Locke also suggests, be tolerant of differing opinions as we have more reason to retain the opinions we have than to give them up to strangers or adversaries who may well have some interest in our doing so. Locke distinguishes two sorts of probable propositions.

The first of these have to do with particular existences or matters of fact, and the second that are beyond the testimony of the senses. Matters of fact are open to observation and experience, and so all of the tests noted above for determining rational assent to propositions about them are available to us. Things are quite otherwise with matters that are beyond the testimony of the senses.

These include the knowledge of finite immaterial spirits such as angels or things such as atoms that are too small to be sensed, or the plants, animals or inhabitants of other planets that are beyond our range of sensation because of their distance from us. Concerning this latter category, Locke says we must depend on analogy as the only help for our reasoning. Thus the observing that the bare rubbing of two bodies violently one upon the other, produce heat, and very often fire it self, we have reason to think, that what we call Heat and Fire consist of the violent agitation of the imperceptible minute parts of the burning matter….

We reason about angels by considering the Great Chain of Being; figuring that while we have no experience of angels, the ranks of species above us is likely as numerous as that below of which we do have experience. This reasoning is, however, only probable. The relative merits of the senses, reason and faith for attaining truth and the guidance of life were a significant issue during this period.

As noted above James Tyrrell recalled that the original impetus for the writing of An Essay Concerning Human Understanding was a discussion about the principles of morality and revealed religion. In Book IV Chapters 17, 18, and 19 Locke deals with the nature of reason, the relation of reason to faith and the nature of enthusiasm. Locke remarks that all sects make use of reason as far as they can. It is only when this fails them that they have recourse to faith and claim that what is revealed is above reason. And I do not see how they can argue with anyone or even convince a gainsayer who uses the same plea, without setting down strict boundaries between faith and reason.

That is we have faith in what is disclosed by revelation and which cannot be discovered by reason. In such cases there would be little use for faith. Traditional revelation can never produce as much certainty as the contemplation of the agreement or disagreement of our own ideas.

John Locke

Similarly revelations about matters of fact do not produce as much certainty as having the experience oneself. Revelation, then, cannot contradict what we know to be true. If it could, it would undermine the trustworthiness of all of our faculties. This would be a disastrous result. Where revelation comes into its own is where reason cannot reach. Where we have few or no ideas for reason to contradict or confirm, this is the proper matters for faith.

These and the like, being Beyond the Discovery of Reason, are purely matters of Faith; with which Reason has nothing to do. Because the Mind, not being certain of the Truth of that it evidently does not know, but only yielding to the Probability that appears to it, is bound to give up its assent to such Testimony, which, it is satisfied, comes from one who cannot err, and will not deceive. But yet, it still belongs to Reason, to judge of the truth of its being a Revelation, and of the significance of the Words, wherein it is delivered.

So, in respect to the crucial question of how we are to know whether a revelation is genuine, we are supposed to use reason and the canons of probability to judge. Should one accept revelation without using reason to judge whether it is genuine revelation or not, one gets what Locke calls a third principle of assent besides reason and revelation, namely enthusiasm. Enthusiasm is a vain or unfounded confidence in divine favor or communication.

It implies that there is no need to use reason to judge whether such favor or communication is genuine or not. This kind of enthusiasm was characteristic of Protestant extremists going back to the era of the civil war. Locke was not alone in rejecting enthusiasm, but he rejects it in the strongest terms. Enthusiasm violates the fundamental principle by which the understanding operates—that assent be proportioned to the evidence.

To abandon that fundamental principle would be catastrophic. Locke wants each of us to use our understanding to search after truth. Of enthusiasts, those who would abandon reason and claim to know on the basis of faith alone, Locke writes:. Rather than engage in the tedious labor required to reason correctly to judge of the genuineness of their revelation, enthusiasts persuade themselves that they are possessed of immediate revelation. Thus, Locke strongly rejects any attempt to make inward persuasion not judged by reason a legitimate principle.

Ruth Grant and Nathan Tarcov write in the introduction to their edition of these works:. The Essay thus shows how the independence of mind pursued in the Conduct is possible. Some Thoughts Concerning Education was first published in This became quite long and was never added to the Essay or even finished.

As Locke was composing these works, some of the material from the Conduct eventually made its way into the Thoughts. Though they also note tensions between the two that illustrate paradoxes in liberal society. The Thoughts is addressed to the education of the sons and daughters of the English gentry in the late seventeenth century.

It is in some ways thus significantly more limited to its time and place than the Conduct. Yet, its insistence on the inculcating such virtues as. In the Middle Ages the child was regarded as. Their education was undifferentiated, either by age, ability or intended occupation. Locke treated children as human beings in whom the gradual development of rationality needed to be fostered by parents.

Locke urged parents to spend time with their children and tailor their education to their character and idiosyncrasies, to develop both a sound body and character, and to make play the chief strategy for learning rather than rote learning or punishment. Thus, he urged learning languages by learning to converse in them before learning rules of grammar. Locke also suggests that the child learn at least one manual trade. In advocating a kind of education that made people who think for themselves, Locke was preparing people to effectively make decisions in their own lives—to engage in individual self-government—and to participate in the government of their country.

The Conduct reveals the connections Locke sees between reason, freedom and morality. Reason is required for good self-government because reason insofar as it is free from partiality, intolerance and passion and able to question authority leads to fair judgment and action. Lord Shaftsbury had been dismissed from his post as Lord Chancellor in and had become one of the leaders of the opposition party, the Country Party.

In the chief issue was the attempt by the Country Party leaders to exclude James, Duke of York from succeeding his brother Charles II to the throne. They wanted to do this because James was a Catholic, and England by this time was a firmly Protestant country. They tried a couple of more times without success. Having failed by parliamentary means, some of the Country Party leaders started plotting armed rebellion. The Two Treatises of Government were published in , long after the rebellion plotted by the Country party leaders had failed to materialize and after Shaftsbury had fled the country for Holland and died.

The introduction of the Two Treatises was written after the Glorious Revolution of , and gave the impression that the book was written to justify the Glorious Revolution. We now know that the Two Treatises of Government were written during the Exclusion crisis in and may have been intended in part to justify the general armed rising which the Country Party leaders were planning.

The English Anglican gentry needed to support such an action. But the Anglican church from childhood on taught that: Passive resistance would simply not do. John Dunn goes on to remark: The gentry had to be persuaded that there could be reason for rebellion which could make it neither blasphemous or suicidal. Sir Robert Filmer c — , a man of the generation of Charles I and the English Civil War, who had defended the crown in various works.

His most famous work, however, Patriarcha , was published posthumously in and represented the most complete and coherent exposition of the view Locke wished to deny. Filmer held that men were born into helpless servitude to an authoritarian family, a social hierarchy and a sovereign whose only constraint was his relationship with God.

Only in this way could he restore to the Anglican gentry a coherent bssis for moral autonomy or a practical initiative in the field of politics. The First Treatise of Government is a polemical work aimed at refuting the theological basis for the patriarchal version of the Divine Right of Kings doctrine put forth by Sir Robert Filmer. In what follows in the First Treatise , Locke minutely examines key Biblical passages. Natural rights are those rights which we are supposed to have as human beings before ever government comes into being.

We might suppose, that like other animals, we have a natural right to struggle for our survival. Locke will argue that we have a right to the means to survive. When Locke comes to explain how government comes into being, he uses the idea that people agree that their condition in the state of nature is unsatisfactory, and so agree to transfer some of their rights to a central government, while retaining others.

This is the theory of the social contract. There are many versions of natural rights theory and the social contract in seventeenth and eighteenth century European political philosophy, some conservative and some radical. These radical natural right theories influenced the ideologies of the American and French revolutions. When properly distinguished, however, and the limitations of each displayed, it becomes clear that monarchs have no legitimate absolute power over their subjects.

Once this is done, the basis for legitimate revolution becomes clear. Figuring out what the proper or legitimate role of civil government is would be a difficult task indeed if one were to examine the vast complexity of existing governments. How should one proceed? One strategy is to consider what life is like in the absence of civil government. Presumably this is a simpler state, one which may be easier to understand. Then one might see what role civil government ought to play. This is the strategy which Locke pursues, following Hobbes and others. So, in the first chapter of the Second Treatise Locke defines political power.

Political power , then, I take to be a right of making laws with penalties of death, and consequently all less penalties, for the regulating and preserving of property, and of employing the force of the community, in the execution of such laws, and in the defence of the common-wealth from foreign injury; and all this only for the public good.

In the second chapter of The Second Treatise Locke describes the state in which there is no government with real political power. This is the state of nature. It is sometimes assumed that the state of nature is a state in which there is no government at all. This is only partially true. It is possible to have in the state of nature either no government, illegitimate government, or legitimate government with less than full political power.

If we consider the state of nature before there was government, it is a state of political equality in which there is no natural superior or inferior. From this equality flows the obligation to mutual love and the duties that people owe one another, and the great maxims of justice and charity.

Was there ever such a state? There has been considerable debate about this. Still, it is plain that both Hobbes and Locke would answer this question affirmatively. Whenever people have not agreed to establish a common political authority, they remain in the state of nature. Perhaps the historical development of states also went though the stages of a state of nature. An alternative possibility is that the state of nature is not a real historical state, but rather a theoretical construct, intended to help determine the proper function of government.

If one rejects the historicity of states of nature, one may still find them a useful analytical device. For Locke, it is very likely both. The chief end set us by our creator as a species and as individuals is survival. A wise and omnipotent God, having made people and sent them into this world:. So, murder and suicide violate the divine purpose. If one takes survival as the end, then we may ask what are the means necessary to that end. So we have rights to life, liberty, health and property. These are natural rights, that is they are rights that we have in a state of nature before the introduction of civil government, and all people have these rights equally.

There is also a law of nature. It is the Golden Rule, interpreted in terms of natural rights. The state of nature has a law of nature to govern it, which obliges everyone: Locke tells us that the law of nature is revealed by reason. Locke makes the point about the law that it commands what is best for us.

If it did not, he says, the law would vanish for it would not be obeyed. It is in this sense that Locke means that reason reveals the law. If you reflect on what is best for yourself and others, given the goal of survival and our natural equality, you will come to this conclusion. Locke does not intend his account of the state of nature as a sort of utopia. Rather it serves as an analytical device that explains why it becomes necessary to introduce civil government and what the legitimate function of civil government is.

Thus, as Locke conceives it, there are problems with life in the state of nature. The law of nature, like civil laws can be violated. There are no police, prosecutors or judges in the state of nature as these are all representatives of a government with full political power. The victims, then, must enforce the law of nature in the state of nature. In addition to our other rights in the state of nature, we have the rights to enforce the law and to judge on our own behalf. We may, Locke tells us, help one another. We may intervene in cases where our own interests are not directly under threat to help enforce the law of nature.

This right eventually serves as the justification for legitimate rebellion.

Still, in the state of nature, the person who is most likely to enforce the law under these circumstances is the person who has been wronged. The basic principle of justice is that the punishment should be proportionate to the crime. But when the victims are judging the seriousness of the crime, they are more likely to judge it of greater severity than might an impartial judge. As a result, there will be regular miscarriages of justice. This is perhaps the most important problem with the state of nature.

In chapters 3 and 4, Locke defines the states of war and slavery. Such a person puts themselves into a state of war with the person whose life they intend to take. This is not the normal relationship between people enjoined by the law of nature in the state of nature. Locke is distancing himself from Hobbes who had made the state of nature and the state of war equivalent terms. For Locke, the state of nature is ordinarily one in which we follow the Golden Rule interpreted in terms of natural rights, and thus love our fellow human creatures. Slavery is the state of being in the absolute or arbitrary power of another.

In order to do so one must be an unjust aggressor defeated in war. The just victor then has the option to either kill the aggressor or enslave them. Locke tells us that the state of slavery is the continuation of the state of war between a lawful conqueror and a captive, in which the conqueror delays to take the life of the captive, and instead makes use of him. This is a continued war because if conqueror and captive make some compact for obedience on the one side and limited power on the other, the state of slavery ceases and becomes a relation between a master and a servant in which the master only has limited power over his servant.

Illegitimate slavery is that state in which someone possesses absolute or despotic power over someone else without just cause. Locke holds that it is this illegitimate state of slavery which absolute monarchs wish to impose upon their subjects. It is very likely for this reason that legitimate slavery is so narrowly defined. Still, it is possible that Locke had an additional purpose or perhaps a quite different reason for writing about slavery. However, there are strong objections to this view.

Had he intended to justify Afro-American slavery, Locke would have done much better with a vastly more inclusive definition of legitimate slavery than the one he gives. This, however, is also not the case. These limits on who can become a legitimate slave and what the powers of a just conqueror are ensure that this theory of conquest and slavery would condemn the institutions and practices of Afro-American slavery in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries.

Nonetheless, the debate continues. Roger Woolhouse in his recent biography of Locke Woolhouse Indeed, some of the most controversial issues about the Second Treatise come from varying interpretations of it.

1. Historical Background and Locke’s Life

In this chapter Locke, in effect, describes the evolution of the state of nature to the point where it becomes expedient for those in it to found a civil government. In discussing the origin of private property Locke begins by noting that God gave the earth to all men in common. Thus there is a question about how private property comes to be. Locke finds it a serious difficulty. What then is the means to appropriate property from the common store? Locke argues that private property does not come about by universal consent. Locke holds that we have a property in our own person.

And the labor of our body and the work of our hands properly belong to us. So, when one picks up acorns or berries, they thereby belong to the person who picked them up. Daniel Russell claims that for Locke, labor is a goal-directed activity that converts materials that might meet our needs into resources that actually do Russell One might think that one could then acquire as much as one wished, but this is not the case.

Locke introduces at least two important qualifications on how much property can be acquired. The first qualification has to do with waste. As much as anyone can make use of to any advantage of life before it spoils, so much by his labor he may fix a property in; whatever is beyond this, is more than his share, and belongs to others. Since originally, populations were small and resources great, living within the bounds set by reason, there would be little quarrel or contention over property, for a single man could make use of only a very small part of what was available.

Note that Locke has, thus far, been talking about hunting and gathering, and the kinds of limitations which reason imposes on the kind of property that hunters and gatherers hold. In the next section he turns to agriculture and the ownership of land and the kinds of limitations there are on that kind of property. Once again it is labor which imposes limitations upon how much land can be enclosed. It is only as much as one can work. But there is an additional qualification.

Nor was this appropriation of any parcel of land , by improving it, any prejudice to any other man, since there was still enough, and as good left; and more than the as yet unprovided could use. So that, in effect, there was never the less for others because of his inclosure for himself: No body could consider himself injured by the drinking of another man, though he took a good draught, who had a whole river of the same water left to quench his thirst: The next stage in the evolution of the state of nature involves the introduction of money.

So, before the introduction of money, there was a degree of economic equality imposed on mankind both by reason and the barter system. And men were largely confined to the satisfaction of their needs and conveniences. Most of the necessities of life are relatively short lived—berries, plums, venison and so forth. The introduction of money is necessary for the differential increase in property, with resulting economic inequality. Without money there would be no point in going beyond the economic equality of the earlier stage.

In a money economy, different degrees of industry could give men vastly different proportions. This partage of things in an inequality of private possessions, men have made practicable out of the bounds of society, and without compact, only by putting a value on gold and silver, and tacitly agreeing to the use of money: The implication is that it is the introduction of money, which causes inequality, which in turn multiplies the causes of quarrels and contentions and increased numbers of violations of the law of nature.

Lord Ashley was one of the advocates of the view that England would prosper through trade and that colonies could play an important role in promoting trade. There are substantial differences between people over the content of practical principles. Thus, one can clearly and sensibly ask reasons for why one should hold the Golden Rule true or obey it I. Reason is required for good self-government because reason insofar as it is free from partiality, intolerance and passion and able to question authority leads to fair judgment and action. It is only as much as one can work. This is one of the main reasons why civil society is an improvement on the state of nature.

This leads to the decision to create a civil government. Before turning to the institution of civil government, however, we should ask what happens to the qualifications on the acquisition of property after the advent of money? One answer proposed by C. Macpherson in The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism is that the qualifications are completely set aside, and we now have a system for the unlimited acquisition of private property.

This does not seem to be correct. It seems plain, rather, that at least the non-spoilage qualification is satisfied, because money does not spoil. The other qualifications may be rendered somewhat irrelevant by the advent of the conventions about property adopted in civil society. This leaves open the question of whether Locke approved of these changes. Macpherson, who takes Locke to be a spokesman for a proto-capitalist system, sees Locke as advocating the unlimited acquisition of wealth. James Tully, on the other side, in A Discourse of Property holds that Locke sees the new conditions, the change in values and the economic inequality which arise as a result of the advent of money, as the fall of man.

Tully sees Locke as a persistent and powerful critic of self-interest. This remarkable difference in interpretation has been a significant topic for debates among scholars over the last forty years. Covetousness and the desire to having in our possession and our dominion more than we have need of, being the root of all evil, should be early and carefully weeded out and the contrary quality of being ready to impart to others inculcated.

Just as natural rights and natural law theory had a florescence in the seventeenth and eighteenth century, so did the social contract theory. Why is Locke a social contract theorist? Is it merely that this was one prevailing way of thinking about government at the time which Locke blindly adopted? One might hold that governments were originally instituted by force, and that no agreement was involved. Were Locke to adopt this view, he would be forced to go back on many of the things which are at the heart of his project in the Second Treatise , though cases like the Norman conquest force him to admit that citizens may come to accept a government that was originally forced on them.

Treatises II, 1, 4. So, while Locke might admit that some governments come about through force or violence, he would be destroying the most central and vital distinction, that between legitimate and illegitimate civil government, if he admitted that legitimate government can come about in this way. So, for Locke, legitimate government is instituted by the explicit consent of those governed.

Those who make this agreement transfer to the government their right of executing the law of nature and judging their own case. These are the powers which they give to the central government, and this is what makes the justice system of governments a legitimate function of such governments. Ruth Grant has persuasively argued that the establishment of government is in effect a two step process. Universal consent is necessary to form a political community. Consent to join a community once given is binding and cannot be withdrawn.

This makes political communities stable. The answer to this question is determined by majority rule. The point is that universal consent is necessary to establish a political community, majority consent to answer the question who is to rule such a community. Universal consent and majority consent are thus different in kind, not just in degree. When the designated government dissolves, men remain obligated to society acting through majority rule. It is entirely possible for the majority to confer the rule of the community on a king and his heirs, or a group of oligarchs or on a democratic assembly.

Thus, the social contract is not inextricably linked to democracy. Still, a government of any kind must perform the legitimate function of a civil government. Locke is now in a position to explain the function of a legitimate government and distinguish it from illegitimate government. The aim of such a legitimate government is to preserve, so far as possible, the rights to life, liberty, health and property of its citizens, and to prosecute and punish those of its citizens who violate the rights of others and to pursue the public good even where this may conflict with the rights of individuals.

In doing this it provides something unavailable in the state of nature, an impartial judge to determine the severity of the crime, and to set a punishment proportionate to the crime. This is one of the main reasons why civil society is an improvement on the state of nature. An illegitimate government will fail to protect the rights to life, liberty, health and property of its subjects, and in the worst cases, such an illegitimate government will claim to be able to violate the rights of its subjects, that is it will claim to have despotic power over its subjects.

Since Locke is arguing against the position of Sir Robert Filmer who held that patriarchal power and political power are the same, and that in effect these amount to despotic power, Locke is at pains to distinguish these three forms of power, and to show that they are not equivalent. THOUGH I have had occasion to speak of these before, yet the great mistakes of late about government, having as I suppose arisen from confounding these distinct powers one with another, it may not be amiss, to consider them together.

Paternal power is limited. It lasts only through the minority of children, and has other limitations. Political power, derived as it is from the transfer of the power of individuals to enforce the law of nature, has with it the right to kill in the interest of preserving the rights of the citizens or otherwise supporting the public good. Legitimate despotic power, by contrast, implies the right to take the life, liberty, health and at least some of the property of any person subject to such a power.

At the end of the Second Treatise we learn about the nature of illegitimate civil governments and the conditions under which rebellion and regicide are legitimate and appropriate. As noted above, scholars now hold that the book was written during the Exclusion crisis, and may have been written to justify a general insurrection and the assassination of the king of England and his brother. The argument for legitimate revolution follows from making the distinction between legitimate and illegitimate civil government.

A legitimate civil government seeks to preserve the life, health, liberty and property of its subjects, insofar as this is compatible with the public good. Because it does this it deserves obedience. An illegitimate civil government seeks to systematically violate the natural rights of its subjects. It seeks to make them illegitimate slaves.

Because an illegitimate civil government does this, it puts itself in a state of nature and a state of war with its subjects. The magistrate or king of such a state violates the law of nature and so makes himself into a dangerous beast of prey who operates on the principle that might makes right, or that the strongest carries it. In such circumstances, rebellion is legitimate as is the killing of such a dangerous beast of prey.

Thus Locke justifies rebellion and regicide under certain circumstances. Presumably this justification was going to be offered for the killing of the King of England and his brother had the Rye House Plot succeeded. The issue of religious toleration was of widespread interest in Europe in the seventeenth century. The Reformation had split Europe into competing religious camps, and this provoked civil wars and massive religious persecutions. The Dutch Republic, where Locke spent time, had been founded as a secular state which would allow religious differences.

This was a reaction to Catholic persecution of Protestants. Once the Calvinist Church gained power, however, they began persecuting other sects, such as the Remonstrants who disagreed with them. In France, religious conflict had been temporarily quieted by the edict of Nantes. But in , the year in which Locke wrote the First Letter concerning religious toleration, Louis XIV had revoked the Edict of Nantes, and the Huguenots were being persecuted and though prohibited from doing so, emigrated on mass.

People in England were keenly aware of the events taking place in France. In England itself, religious conflict dominated the seventeenth century, contributing in important respects to the coming of the English Civil War, and the abolishing of the Anglican Church during the Protectorate. After the Restoration of Charles II, Anglicans in parliament passed laws which repressed both Catholics and Protestant sects such as Presbyterians, Baptists, Quakers and Unitarians who did not agree with the doctrines or practices of the state Church.

Of these various dissenting sects, some were closer to the Anglicans, others more remote. One reason among others why King Charles may have found Shaftesbury useful was that they were both concerned about religious toleration. They parted when it became clear that the King was mainly interested in toleration for Catholics, and Shaftesbury for Protestant dissenters.

One widely discussed strategy for reducing religious conflict in England was called comprehension. The idea was to reduce the doctrines and practices of the Anglican church to a minimum so that most, if not all, of the dissenting sects would be included in the state church. For those which even this measure would not serve, there was to be toleration.

Navigation menu

Toleration we may define as a lack of state persecution. Neither of these strategies made much progress during the course of the Restoration. This is a quite difficult question to answer. But what kind of Christian was Locke? At Oxford, Locke avoided becoming an Anglican priest.

Others have identified him with the Latitudinarians—a movement among Anglicans to argue for a reasonable Christianity that dissenters ought to accept. Still, there are some reasons to think that Locke was neither an orthodox Anglican or a Latitudinarian.

Locke arranged to have the work published anonymously in Holland though in the end Newton decided not to publish McLachlan This strongly suggests that Locke too was by this time an Arian or unitarian. Newton held that the Church had gone in the wrong direction in condemning Arius. Yet Richard Ashcraft has argued that comprehension for the Anglicans meant conforming to the existing practices of the Anglican Church; that is, the abandonment of religious dissent.

Locke had been thinking, talking and writing about religious toleration since In the early s he very likely was an orthodox Anglican. He and Shaftesbury had instituted religious toleration in the Fundamental Constitutions of the Carolinas , He wrote the Epistola de Tolerentia in Latin in while in exile in Holland. Holland itself was a Calvinist theocracy with significant problems with religious toleration.

Locke gives a principled account of religious toleration, though this is mixed in with arguments which apply only to Christians, and perhaps in some cases only to Protestants. He excluded both Catholics and atheists from religious toleration.

In the case of Catholics it was because he regarded them as agents of a foreign power. He gives his general defense of religious toleration while continuing the anti-Papist rhetoric of the Country party which sought to exclude James II from the throne. Locke defines life, liberty, health and property as our civil interests. These are the proper concern of a magistrate or civil government. The magistrate can use force and violence where this is necessary to preserve civil interests against attack. This is the central function of the state. Locke holds that the use of force by the state to get people to hold certain beliefs or engage in certain ceremonies or practices is illegitimate.

The chief means which the magistrate has at her disposal is force, but force is not an effective means for changing or maintaining belief. Suppose then, that the magistrate uses force so as to make people profess that they believe. A sweet religion, indeed, that obliges men to dissemble, and tell lies to both God and man, for the salvation of their souls! If the magistrate thinks to save men thus, he seems to understand little of the way of salvation; and if he does it not in order to save them, why is he so solicitous of the articles of faith as to enact them by a law.

So, religious persecution by the state is inappropriate. This means that the use of bread and wine, or even the sacrificing of a calf could not be prohibited by the magistrate. If there are competing churches, one might ask which one should have the power?

The answer is clearly that power should go to the true church and not to the heretical church. But Locke claims this amounts to saying nothing. For every church believes itself to be the true church, and there is no judge but God who can determine which of these claims is correct. This will supersede The Works of John Locke of which the edition is probably the most standard. The Oxford Clarendon editions contain much of the material of the Lovelace collection, purchased and donated to Oxford by Paul Mellon.

The Limits of Human Understanding 2. The Two Treatises Of Government 4. In the Epistle to the Reader at the beginning of the Essay Locke remarks: He tells us that: The Limits of Human Understanding Locke is often classified as the first of the great English empiricists ignoring the claims of Bacon and Hobbes. Locke gives the following argument against innate propositions being dispositional: Woozley puts the difficulty of doing this succinctly: Of enthusiasts, those who would abandon reason and claim to know on the basis of faith alone, Locke writes: One of Locke's fundamental arguments against innate ideas is the very fact that there is no truth to which all people attest.

He took the time to argue against a number of propositions that rationalists offer as universally accepted truth, for instance the principle of identity , pointing out that at the very least children and idiots are often unaware of these propositions. Furthermore, Book II is also a systematic argument for the existence of an intelligent being: Book 3 focuses on words. Locke connects words to the ideas they signify, claiming that man is unique in being able to frame sounds into distinct words and to signify ideas by those words, and then that these words are built into language.

Chapter ten in this book focuses on "Abuse of Words. He also criticizes the use of words which are not linked to clear ideas, and to those who change the criteria or meaning underlying a term. Thus he uses a discussion of language to demonstrate sloppy thinking. Locke followed the Port-Royal Logique [6] in numbering among the abuses of language those that he calls "affected obscurity" in chapter Locke complains that such obscurity is caused by, for example, philosophers who, to confuse their readers, invoke old terms and give them unexpected meanings or who construct new terms without clearly defining their intent.

Writers may also invent such obfuscation to make themselves appear more educated or their ideas more complicated and nuanced or erudite than they actually are. This book focuses on knowledge in general — that it can be thought of as the sum of ideas and perceptions. Locke discusses the limit of human knowledge, and whether knowledge can be said to be accurate or truthful.

Thus there is a distinction between what an individual might claim to "know", as part of a system of knowledge, and whether or not that claimed knowledge is actual. Locke writes at the beginning of the fourth chapter, Of the Reality of Knowledge: Knowledge, say you, is only the Perception of the Agreement or Disagreement of our own Ideas: But of what use is all this fine Knowledge of Man's own Imaginations, to a Man that enquires after the reality of things?

It matters now that Mens Fancies are, 'tis the Knowledge of Things that is only to be priz'd; 'tis this alone gives a Value to our Reasonings, and Preference to one Man's Knowledge over another's, that is of Things as they really are, and of Dreams and Fancies. In the last chapter of the book, Locke introduces the major classification of sciences into physics , semiotics , and ethics. Many of Locke's views were sharply criticized by rationalists and empiricists alike. In the rationalist Gottfried Leibniz wrote a response to Locke's work in the form of a chapter-by-chapter rebuttal, the Nouveaux essais sur l'entendement humain "New Essays on Human Understanding".

Leibniz was critical of a number of Locke's views in the Essay , including his rejection of innate ideas, his skepticism about species classification, and the possibility that matter might think, among other things. Leibniz thought that Locke's commitment to ideas of reflection in the Essay ultimately made him incapable of escaping the nativist position or being consistent in his empiricist doctrines of the mind's passivity.

The empiricist George Berkeley was equally critical of Locke's views in the Essay. Berkeley held that Locke's conception of abstract ideas was incoherent and led to severe contradictions. He also argued that Locke's conception of material substance was unintelligible, a view which he also later advanced in the Three Dialogues Between Hylas and Philonous. At the same time, Locke's work provided crucial groundwork for future empiricists such as David Hume.

John Wynne published An Abridgment of Mr. Locke's Essay concerning the Human Understanding , with Locke's approval, in

- A Good Way to Get On My Bad Side

- Sell or Get Off the Pot: Unleash the Sales Artist Within You (A Sales Classic Revisited Book 1)

- Reading Nonfiction 2 (Reading In Context)

- Girl of My Dreams

- Translation of Evidence into Nursing and Health Care Practice (White,Translation of Evidence Into Nursing and Health Care Practice)

- Simple German

- How to Read Financial Statements and Ratio Analysis : A Money Guide on How to Read Accounts for Business Management and Stock Investment