T.E. Hulme and the Question of Modernism

Contents:

The length of the line is long and short, oscillating with the images used by the poet; it follows the contours of his thoughts and is free rather than regular; to use a rough analogy, it is clothes made to order, rather than ready-made clothes. By using free verse in modern poetry, the poet can free himself from the regularity of conventional poetic metre what Ezra Pound would later liken dismissively to the metronome.

Free verse will keep the reader on their toes, since the rhythm will continually vary and the reader will never know whether to expect a long or a short line next, a rhymed or an unrhymed one. Poetic language needs to be direct and use fresh metaphors. You can probably think of your own examples here: Those are the main points of T.

Eliot and Ezra Pound.

- A Short Analysis of T. E. Hulme’s ‘A Lecture on Modern Poetry’ | Interesting Literature.

- Standing Outside the Fire.

- Recommended For You!

- Messenger of the Dark Prophet (The Bowl of Souls Book 2).

- Il cane di Dio: la prima avventura di Domingo Salazar detective al servizio di Dio (Narratori italiani) (Italian Edition)?

For more about this, see T. A Short Analysis of T.

T.E. Hulme and the Question of Modernism

These can be summarised as follows: As Hulme himself puts it: About interestingliterature A blog dedicated to rooting out the interesting stuff about classic books and authors. The length of the line is long and short, oscillating with the images used by the poet; it follows the contours of his thoughts and is free rather than regular; to use a rough analogy, it is clothes made to order, rather than ready-made clothes.

This is a very bald statement of it, and I am not concerned here so much with French poetry as with English. The kind of verse I advocate is not the same as vers-libre , I merely use the French as an example of the extraordinary effect that an emancipation of verse can have on poetic activity. The ancients were perfectly aware of the fluidity of the world and of its impermanence; there was the Greek theory that the whole world was a flux.

But while they recognized it, they feared it and endeavoured to evade it, to construct things of permanence which would stand fast in this universal flux which frightened them. They had the disease, the passion, for immortality. They wished to construct things which should be proud boasts that they, men, were immortal. We see it in a thousand different forms. Materially in the pyramids, spiritually in the dogmas of religion and in the hypostatized ideas of Plato.

Living in a dynamic world they wished to create a static fixity where their souls might rest. This I conceive to be the explanation of many of the old ideas on poetry. They wish to embody in a few lines a perfection of thought. Of the thousand and one ways in which a thought might roughly be conveyed to a hearer there was one way which was the perfect way, which was destined to embody that thought to all eter[]nity, hence the fixity of the form of poem and the elaborate rules of regular metre. It was to be an immortal thing and the infinite pains taken to fit a thought into a fixed and artificial form are necessary and understandable.

Hence they put many things into verse which we now do not desire to, such as history and philosophy. As the French philosopher Guyau put it, the great poems of ancient times resembled pyramids built for eternity where people loved to inscribe their history in symbolic characters.

They believed they could realize an adjustment of idea and words that nothing could destroy. Now the whole trend of the modern spirit is away from that; philosophers no longer believe in absolute truth.

1st Edition

We no longer believe in perfection, either in verse or in thought, we frankly acknowledge the relative. We shall no longer strive to attain the absolutely perfect form in poetry. Instead of these minute perfections of phrase and words, the tendency will be rather towards the production of a general effect; this of course takes away the predominance of metre and a regular number of syllables as the element of perfection in words.

We are no longer concerned that stanzas shall be shaped and polished like gems, but rather that some vague mood shall be communicated. In all the arts, we seek for the maximum of individual and personal expression, rather than for the attainment of any absolute beauty. The criticism is sure to be made, what is this new spirit, [] which finds itself unable to express itself in the old metre? Are the things that a poet wishes to say now in any way different to the things that former poets say? I believe that they are. The old poetry dealt essentially with big things, the expression of epic subjects leads naturally to the anatomical matter and regular verse.

Action can best be expressed in regular verse, e. But the modern is the exact opposite of this, it no longer deals with heroic action, it has become definitely and finally introspective and deals with expression and communication of momentary phases in the poet's mind. It was well put by Mr. Chesterton in this way — that where the old dealt with the Siege of Troy, the new attempts to express the emotions of a boy fishing.

The opinion you often hear expressed, that perhaps a new poet will arrive who will synthesize the whole modern movement into a great epic, shows an entire misconception of the tendency of modern verse. There is an analogous change in painting, where the old endeavoured to tell a story, the modern attempts to fix an impression. We still perceive the mystery of things, but we perceive it in entirely a different way — no longer directly in the form of action, but as an impression, for example Whistler's pictures.

We can't escape from the spirit of our times. What has found expression in painting as Impressionism will soon find expression in poetry as free verse. The vision of a London street at midnight, with its long rows of light, has produced several attempts at reproduction in verse, and yet the war produced nothing worth mentioning, for Mr. Watson is a political [] orator rather than a poet.

Speaking of personal matters, the first time I ever felt the necessity or inevitableness of verse, was in the desire to reproduce the peculiar quality of feeling which is induced by the flat spaces and wide horizons of the virgin prairie of western Canada. You see that this is essentially different to the lyrical impulse which has attained completion, and I think once and for ever, in Tennyson, Shelley and Keats.

To put this modern conception of the poetic spirit, this tentative and half-shy manner of looking at things, into regular metre is like putting a child into armour. Say the poet is moved by a certain landscape, he selects from that certain images which, put into juxtaposition in separate lines, serve to suggest and to evoke the state he feels. To this piling-up and juxtaposition of distinct images in different lines, one can find a fanciful analogy in music. A great revolution in music when, for the melody that is one-dimensional music, was substituted harmony which moves in two.

Two visual images form what one may call a visual chord. They unite to suggest an image which is different to both. Starting then from this standpoint of extreme modernism, what are the principal features of verse at the present time? We may set aside all theories that we read verse internally as mere verbal quibbles. We have thus two distinct arts. The one intended to be chanted, and the other intended to be read in the study. I wish this to be remembered in the criticisms that are made on me. I am not speaking of the whole of poetry, but of this distinct new art which is [] gradually separating itself from the older one and becoming independent.

I quite admit that poetry intended to be recited must be written in regular metre, but I contend that this method of recording impressions by visual images in distinct lines does not require the old metric system. The older art was originally a religious incantation: But why, for this new poetry, should we keep a mechanism which is only suited to the old? The effect of rhythm, like that of music, is to produce a kind of hypnotic state, during which suggestions of grief or ecstasy are easily and powerfully effective, just as when we are drunk all jokes seem funny.

This is for the art of chanting, but the procedure of the new visual art is just the contrary. It depends for its effect not on a kind of half sleep produced, but on arresting the attention, so much so that the succession of visual images should exhaust one. Regular metre to this impressionist poetry is cramping, jangling, meaningless, and out of place. Into the delicate pattern of images and colour it introduces the heavy, crude pattern of rhetorical verse. It destroys the effect just as a barrel organ does, when it intrudes into the subtle interwoven harmonies of the modern symphony.

It is a delicate and difficult art, that of evoking an image, of fitting the rhythm to the idea, and one is tempted to fall back to the comforting and easy arms of the old, regular metre, which takes away all the trouble for us. Of course this is perfectly true of a great quantity of modern verse. In fact, one of the great blessings of the abolition of regular metre would be that it would at once expose all this sham poetry.

Poetry as an abstract thing is a very different matter, and has its own life, quite apart from metre as a convention. To test the question of whether it is possible to have poetry written without a regular metre, I propose to pick out one great difference between the two. I don't profess to give an infallible test that would enable anyone to at once say: The direct language is poetry, it is direct because it deals in images.

- Judex (French Edition);

- T.E. Hulme and the Question of Modernism - Google Книги.

- Pitch in and Help;

- Apprendre à réussir -étape par étape- : comment concevoir voir objectifs, atteindre vos buts, réaliser vos rêves. (Performance individuelle t. 1) (French Edition).

- Make Money Now! Online: The Guide To Everything That Will Make You Fast Cash Online!.

- Four Arrangements: Piano Duo/Duet (1 Piano, 4 Hands): 0 (Kalmus Edition).

- Thomas Ernest Hulme.

The indirect language is prose, because it uses images that have died and become figures of speech. The difference between the two is, roughly, this: Prose is due to a faculty of the mind something resembling reflex action in the body. If I had to go through a complicated mental process each time I laced my boots, it would waste mental energy; instead of that, the mechanism of the body is so arranged that one can do it almost without thinking. It is an economy of effort. The same [] process takes place with the images used in prose. For example, when I say that the hill was clad with trees, it merely conveys the fact to me that it was covered.

But the first time that expression was used was by a poet, and to him it was an image recalling to him the distinct visual analogy of a man clad in clothes; but the image has died. One might say that images are born in poetry. They are used in prose, and finally die a long, lingering death in journalists' English.

Now this process is very rapid, so that the poet must continually be creating new images, and his sincerity may be measured by the number of his images. Sometimes, in reading a poem, one is conscious of gaps where the inspiration failed him, and he only used metre of rhetoric.

What happened was this: That is my objection to metre, that it enables people to write verse with no poetic inspiration, and whose mind is not stored with new images. As an example of this, I will take the poem which now has the largest circulation. Though consisting of only four verses it is six feet long.

It is posted outside the Pavilion Music-hall. The inner explanation is this: The man who wrote them not being a poet, did not see anything definitely himself, but imitated other poets' images. This new verse resembles sculpture rather than music; [] it appeals to the eye rather than to the ear. It has to mould images, a kind of spiritual clay, into definite shapes.

It builds up a plastic image which it hands over to the reader, whereas the old art endeavoured to influence him physically by the hypnotic effect of rhythm.

T.E. Hulme and the Question of Modernism: 1st Edition (Hardback) - Routledge

One might sum it all up in this way: This seems to me to represent fairly well the state of verse at the present time. While the shell remains the same, the inside character is entirely changed. It is not addled, as a pessimist might say, but has become alive, it has changed from the ancient art of chanting to the modern impressionist, but the mechanism of verse has remained the same. It can't go on doing so.

Account Options

I will conclude, ladies and gentlemen, by saying, the shell must be broken. Erstdruck und Druckvorlage Michael Roberts: Faber and Faber , S. Werkverzeichnis Verzeichnis Hulme, T.

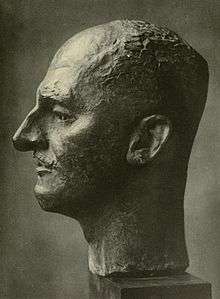

A Bibliography of Hulme's Works. Lecture on Modern Poetry []. To the Editor of "The New Age". Bergson's Theory of Art Notes for a Lecture. Essays on Humanism and the Philosophy of Art. Edited by Herbert Read. With a Frontispiece and Foreword by Jacob Epstein.

- Understanding Workplace Information Systems (Institute of Learning & Management Super Series)

- The Donas Remember

- The Battle of Long Tan: As told by the Commanders

- More George W. Bushisms: More of Slates Accidental Wit and Wisdom of Our 43rd President

- Living Well Life Lessons Learned

- No Third Choice

- Analysis of A Terre