The Legend of the Scarlet Ravine and other Tales to Chill your Bones

Contents:

There are settlements already, where a woodsman cannot find his way for the roads and farms. At this moment the tread of a horse was heard. The hunter threw his rifle over his arm, and stepped behind a large tree, to be prepared for friend or foe. In a moment, Edward Overton made his appearance, dashing along the war-path. His horse was panting and covered with foam, his dress torn, and his countenance haggard.

The hunter emerged from his concealment to meet him. They were strangers to each other, but no time was lost in useless ceremony or unnecessary questions, and Edward soon related the catastrophe of the preceding evening. Very much of a gentleman, I expect—he came from Culpepper—I killed a deer once in sight of his plantation—though I never saw the man, to know him. Well the way these Indians act is curious.

But where is your company? The hunter then related what he had seen, and the youth, elate with new hope, urged an instant pursuit. Even now she may be at the stake. The savages treat their prisoners very ridiculously sometimes. But, young gentleman, I see you carry a fine looking rifle,—can you handle it well. Never fear me—I will stand by you. I would die a thousand deaths for that dear girl. If there is not good Virginia blood in you, I am mistaken. The misfortune is that a man can only die once, however willing he might be to try it over again.

Product description

Well, there is nothing gained without risk— and I feel for this poor child. Don't be in a fret, young man, I am just waiting to let you take breath. I will go with you provided you will obey my instructions. Now, mark what I say: It will be curious if we two cannot outgeneral a half a dozen naked Mingoes. The former apathy of the hunter's manner had entirely vanished. The excitement was sufficient to call out his energies.

His eye was lighted up with martial ardour, his lips were compressed, and his step firm and elastic. Without waiting for further parley, he dashed forward, with a rapid stride, followed by his young and not less gallant companion. With unerring sagacity he struck at once into the trail of the enemy. Blood for blood is the backwoodsman's rule. We shall have them at the first halt they make. They cannot travel all the time, without stopping, no more than white folks. The hunter now advanced with astonishing rapidity, for although his step seemed to be deliberate, it had a steadiness and vigour, which yielded to no obstacle.

His course was as direct as the flight of a bee, and his footsteps, owing to a peculiar and habitual mode of walking, were perfectly noiseless, except when the dry twigs cracked under the weight of his body. His eye was continually bent on the ground, at some distance in advance of his course; for he tracked the enemy not so much by the footprints on the soil, as by the derangement of the dry leaves or growing foliage.

The upper side of a leaf is of a deep green colour and glossy smoothness; the under side is paler, and of a rougher texture, and when turned by violence from its proper position, it will spontaneously return to it in a few hours, and again expose the polished surface to the rays of light. The hunter is aware of this fact, and in attentively observing the arrangement of the foliage of the tender shrubs, discovers, with wonderful acuteness, whether the leaves retain their natural position. So true is this indication, that where the grass is thick and tangled, a track of lighter hue than the general surface, may be distinctly seen for hours after the leaves have been disturbed.

The occasional rupture of a twig, and the displacing of the branches in the thickets afford additional signs; and in places where the ground is soft, the foot prints are carefully noticed. Other cares, also, claimed the attention of the woodsman. His vigilant glance was often thrown far abroad. He approached every covert, or place of probable concealment, with caution, and sometimes when the trail passed through dangerous defiles, where the enemy might be lurking, suddenly forsook it, and taking a wide circuit, struck into it again far in advance.

Thus they proceeded for three hours, with unremitting diligence and silence, when the pioneer halted. The youth, whose confidence in his guide was now complete, obeyed in silence. The hunter again examined his arms. It is a pleasant thing to have a gun that will not deceive you in the hour of danger. But then a man must do his duty, and have every thing in order. Overton had been accustomed all his life to hunt occasionally for amusement. He was a young man of considerable muscular powers, and possessing the high spirit, and the apitude in the use of weapons, which are so characteristic of the youth of his country, was no mean proficient in the exercises of the forest.

He now followed the example of his guide. They laid aside their coats and hats, drew their belts closely, and began to advance slowly, taking every step with such caution as not to create the slightest sound. They soon reached the summit of a small eminence, when the backwoodsman halted, crouched low, and pointed forwards with his finger.

Overton followed with his eye the direction indicated, and beheld with emotions of indescribable delight, mingled with agony, the objects of his pursuit. At the root of a large tree sate the Indians, hideously painted, and fully equipped for battle, voraciously devouring their hasty meal. At a few yards distance from them knelt Ellen, in the posture already described, awaiting her fate with all the courage of conscious innocence, and all the resignation of fervent piety. Overton's emotion was so great, that the hunter with difficulty drew him to the ground, while he hastily whispered the plan of attack, a part of which had been concerted at their recent halt.

I will shoot at that large warrior who is standing alone—you will aim at one of those who are sitting; the moment we have fired we will load again, without moving, shouting all the while, and making as much noise as possible;—be cool—my dear young friend — be cool. Overton smothered his feelings, and during the conflict emulated the presence of mind of his companion. They crept on their hands and knees to the fallen trunk of a large tree, which lay between them and the enemy, and having taken a deliberate aim, the hunter gave the signal, and both fired.

Two of the savages fell, the others seized their arms, while our heroic Kentuckians reloaded, shouting all the while.

Ellen started up, uttering a shriek of joy, and rushed towards her friends. Two of the enraged Indians pursued, with the intention of dispatching her, before they should retreat. Edward Overton and his companion rushed to her assistance. One of the Indians had caught her long hair, which streamed behind her, in her flight, and his tomahawk glittered above his head, when Edward rushed between them, and received the blow, diminished in force, on his own arm.

Undaunted, he threw himself on the bosom of the savage, and they rolled together on the ground, in fierce conflict. The hunter advanced upon his adversary more deliberately, and practising a stratagem, clubbed his rifle. The Indian, deceived into the belief that his piece was not charged, stopped, and was about to throw his tomahawk, when the backwoodsman, adroitly bringing the gun to his shoulder, shot him dead. Two other foemen remained, and were rushing upon the intrepid hunter, when the latter perceiving that the struggle between Overton and his antagonist was still fierce and doubtful, hastened to his assistance, and with a single blow of his knife, decided the combat.

Edward sprung up, reeking with blood, and stood manfully by his friend, prepared for a new encounter; but the parties being now equal in number, the two remaining savages retreated. In another moment Miss Singleton was in the arms of the heroic Overton.

We shall not attempt to describe the joy of the young lovers. Ellen, who had thus far sustained herself with a noble courage, and whose resignation to her fate, dictated by an elevated principle of religious confidence, had won the admiration of her savage captors, and perhaps preserved her life, now felt the tender affections of the woman resuming their gentle dominion in her bosom. The faith, the hope which had supported her, though resulting from rational deductions, had been almost superhuman in their operation; but the gratitude to Heaven that now swelled her heart, and burst in impassioned eloquence from her lips, was warm from the native fountains of sensibility.

Sudden deliverance from all the horrors by which she had been surrounded, was in itself sufficiently joyful; but it came infinitely enhanced in value, when brought by the hand of her lover; and when Edward Overton found that, though fatigued and bruised, she had suffered no material injury, his joy knew no bounds. As for the hunter, he was engaged, like a prudent general, in securing the victory. He had carefully reloaded his gun, and having with his dog pursued the fugitives for a short distance, to ascertain that they were not lurking near, began to inspect the bodies of the slain, and collect their arms.

Some of our people want arms badly, and these will just suit. As he surveyed the field of battle, a flush of triumph was on his cheek; but it was evident that his paramount feelings were those of a benevolent nature, and that his sympathies were deeply enlisted. This has been a sorrowful night to both of them, but they will look back to it hereafter with grateful hearts. They did not know before how much they thought of each other. In a few minutes a shout was heard, and another hunter, clad like the first, joined them. I have been on the trail all the morning. I knew the crack of your rifle, when I heard it, and hurried on.

But I could n't get here no sooner, no how. Well, there's always plenty of help when it's not wanted. The woods is alive with rangers. I took a short cut about a mile back, and left them. I never saw such a turn out, no how. The camp ground was emptied spontenaciously , in a few minutes after the news came. How do you stand it, Madam? These Mingoes act mighty redick'lous with women and children. They aint the raal true grit , no how. A party of horsemen now arrived, among whom was Mr Singleton. A litter was soon prepared for the rescued lady, who was borne on the shoulders of men, in joy and triumph, to the settlement, and found herself repaid for her sufferings by the assiduous attentions and affectionate congratulations of her friends and neighbours.

When Mr Singleton had heard the particulars of the rescue, he pressed the happy Overton to his bosom, and looked round for the brave hunter, to whom he owed so deep a debt of gratitude, but he was no where to be seen. On the arrival of the horsemen, he had given the trophies of the fight in charge to one of them, and retired with his companion.

Mr Singleton was deeply chagrined, for he felt a sense of obligation to the generous backwoodsman, which, as he knew that no other compensation would be received, he wished to acknowledge. He is on the trail of the two that fled, and will have them before he sleeps. No sooner was this communication made, than a party set out to join in the pursuit, and it was afterwards understood that they overtook the veteran pioneer, only in time to participate in the last scene of the tragedy of that eventful day.

Ellen Singleton recovered her health rapidly, and the wedding took place on the day that had been appointed. Agreeably to the hospitable custom of this country, a general invitation was given, and the whole neighbourhood was assembled.

They had already collected, when Mr Singleton joined them, in company with the veteran woodsman, the most conspicuous character in this legend. He was now dressed like a plain respectable country gentleman. His carriage was erect, and his person seemed more slender than when cased in buckskin. Though perfectly simple and unstudied in his manners, there was nothing in them of the clownish or bashful, but a dignity, and even an ease approaching to gracefulness. His countenance was cheerful and benevolent, and in his fine eye there was a manly confidence mingled with a softness of expression, which afforded a true index of the character of the man.

His hair, a little thinned, and slightly silvered with age, gave a venerable appearance to his otherwise vigorous and elastic form. His agreeable smile, his well known artlessness of character, and amiability of life, as well as his public services, rendered him an universal favourite, and his entrance caused a murmur of pleasure. But as the happiness of this occasion would have been incomplete without him, I have presevered. And now, my friends and neighbours, allow me to acknowledge publicly my gratitude for his intrepid conduct on the late mournful occasion, when my only child was rescued from a dreadful captivity by his generous interference; and to exert the last act of my parental authority by decreeing that the first kiss of the bride shall be given to the pioneer of the west —the Patriarch of Kentucky.

On a pleasant evening in the autumn of the year 18—, two travellers were slowly winding their way along a narrow road which led among the hills that overhang the Cumberland river, in Tennessee. One of these was a farmer of the neighbourhood— a large, robust, sunburnt man, mounted on a sleek plough horse. He was one of the early settlers, who had fought and hunted in his youth, among the same valleys that now teemed with abundant harvests; a rough plain man clad in substantial homespun, he had about him an air of plenty and independence, which is never deceptive, and which belongs almost exclusively to our free and fertile country.

His companion was of a different cast—a small, thin, grey haired man, who seemed worn down by bodily or mental fatigue to almost a shadow.

theChroniclesofaMillinneumHousewife

He was a preacher, but one who would have deemed it an insult to be called a clergyman; for he belonged to a sect who contemn all human learning as vanity, and who consider a trained minister as little better than an impostor. The person before us was a champion of the sect. He boasted that he had nearly grown to manhood, before he knew one letter from another; that he had learned to read for the sole purpose of gaining access to the scriptures, and, with the exception of the hymns used in his church, had never read a page in any other book.

With considerable natural sagacity, and an abundance of zeal, he had a gift of words, which enabled him at times to support his favourite tenets with a plausibility and force, amounting to something very nearly akin to eloquence, and which, while it gave him unbounded sway among his own followers, was sometimes not a little troublesome to his learned opponents. His sermons presented a curious mixture of the sententious and the declamatory, an unconnected mass of argument and assertion, through which there ran a vein of dry original humour, which, though it often provoked a smile, never failed to rivet the attention of the audience.

But these flashes were like sparks of fire, struck from a rock; they communicated a life and warmth to the hearts of others, which seemed to have no existence in that from which they sprung, for that humour never flashed in his own eye, nor relaxed a muscle of his melancholy, cadaverous countenance. His ideas were not numerous, and the general theme of his declamation consisted of metaphysical distinctions between what he called "head religion," and "heart religion;" the one being a direct inspiration, and the other a spurious substitute learned from vain books.

He wrote a tract to show it was the thirst after human knowledge, which drove our first parents from paradise, that through the whole course of succeeding time school larning had been the most prolific source of human misery and mental degradation, and that bible societies, free masonry, the holy alliance, and the inquisition, were so many engines devised by king-craft, priest-craft, and school-craft, to subjugate the world to the power of Satan.

He spoke of the millennium as a time when "there should be no king, nor printer, nor Sunday school, nor outlandish tongue, nor vain doctrine—when men would plough, and women milk the cows, and talk plain English to each other, and worship God out of the fulness of their hearts, and not after vain forms written by men. Honest, humane and harmless in private life, impetuous in his feelings, fearless and independent by nature, and reared in a country where speech is as free as thought, he pursued his vocation without intolerance, but with a zeal which sometimes bordered on insanity.

He spoke of his opponents more in sorrow than in anger, and bewailed the increase of knowledge as a mother mourns over her first born. He was of course ignorant and illiterate; and with a mind naturally vigorous, and capable of high attainments, his visionary theories, and perhaps a slight estrangement of intellect, had left the soil open to superstition, so that while at one time he discovered and exposed a popular error with wonderful acuteness, at another he blindly adopted the grossest fallacy.

Such was Mr Zedekiah Bangs. His innocent and patriarchal manners insured him universal esteem, and rendered him famous, far and wide, under the title of Uncle Zeddy; while his acknowledged zeal and sanctity gained for him in his own church, and among the religious generally, the more reverend appellation of Father Bangs.

Our worthy preacher, having no regular stipend— for he would have scorned to preach for the lucre of gain, cultivated a small farm, or as the phrase is, raised a crop , in the summer, for the subsistence of his family. During this season he ministered diligently among his neighbours; but in the autumn and winter his labours were more extensive. Then it was that he mounted his nag, and rode forth to spread his doctrines, and to carry light and encouragement to the numerous churches of his sect.

Then it was that he travelled thousands of miles, encountering every extreme of fatigue and privation, and every vicissitude of climate, seldom sleeping twice in the same bed, or eating two meals at the same place, and counting every day lost in which he did not preach a sermon.

Gentlemen who pursue the same avocation with praiseworthy assiduity in other countries, have little notion of the hardships which are endured by the class of men of whom I am writing. Living on the frontier, where the settlements are separated from each other by immense tracts of wilderness, they brave toil and hunger with the patience of the hunter. They traverse pathless wilds, swim rivers, encamp in the open air, and learn the arts, while they acquire the hardihood of backwoodsmen.

Such were the labours of our worthy preacher; yet he would accept no pay; requiring only his food and lodging, which are always cheerfully accorded, at every dwelling in the west, to the travelling minister. Among his converts was Johnson, the farmer in whose company we found him at the commencement of this history. Tom Johnson, as he was familiarly called, had been a daring warrior and hunter, in the first settlement of this country.

When times became peaceable he married and settled down, and, as is not unusual, by the mere rise in value of his land, and the natural increase of his stock, became in a few years comparatively wealthy, with but little labour. A state of ease and affluence was not without its dangers to a man of his temperament and desultory habits; and Tom was beginning to become what in this country is called a "Rowdy," that is to say, a gentleman of pleasure , without the high finish which adorns that character in more polished societies.

He "swapped" horses, bred fine colts, and attended at the race paths; he frequented all public meetings, talked big at elections, and was courted by candidates for office; he played loo , drank deep, and on proper occasions "took a small chunk of a fight. Tom "got religion" at a camp-meeting, and for a while was quite a reformed man. Then he relapsed a little, and finally settled down into a doubtful state, which the church could not approve, yet could not conveniently punish. He neither drank nor swore; he wore the plain dress, kept the Sabbath, attended meetings, and gave a cordial welcome to the clergy at his house.

But he had not sold his colts; he went sometimes to the race ground; he could count the run of the cards and the chances of candidates; and it was even reported that he had betted on the high trump. From this state he was awakened by Father Bangs, who boldly arraigned him as a backslider. On this occasion, the good man, having preached in the vicinity, was going to spend the night with his friend Johnson.

As the travellers passed along, I am not aware that either of them cast a thought upon the romantic and picturesque beauties by which they were surrounded. The banks of the Cumberland, at this point, are rocky and precipitous; sometimes presenting a parapet of several hundred feet in height, and sometimes shooting up into cliffs, which overhang the stream.

The river itself, rushing through the deep abyss, appears as a small rivulet to the beholder; the steam-boats, struggling with mighty power against the rapid current, are diminished to the eye, while the roaring of the steam and the rattling of wheels come exaggerated by a hundred echoes. The travellers halted to gaze at one of these vessels, which was about to ascend a difficult pass, where the river, confined on either side by jutting rocks, rushed through the narrow channel with increased volocity.

The prow of the boat plunged into the swift current, dashing the foam over the deck. Then it paused and trembled; a powerful conflict succeeded, and for a time the vessel neither advanced nor receded. Her struggles resembled those of an animated creature. Her huge hull seemed to writhe upon the water. The rapid motion of the wheels, the increased noise of the engine, the bursting of the escape-steam from the valve, showed that the impelling power had been raised to the highest point.

It was a moment of thrilling suspense. A slight addition of power would enable the boat to advance,—the least failure, the slightest accident, would expose her to the fury of the torrent and dash her on the rocks. Thus she remained for several minutes; then resuming her way, crept heavily over the ripple, reached the smooth water above, and darted swiftly forward. We had vain and idle devices enough to lead our minds off from our true good, without these smoking furnaces of Satan, these floating towers of Babel, that belch forth huge volumes of brimstone, and seduce honest men and women from home, to go visiting around the land in large companies, and talk to each other in strange tongues.

There was no printing-office in Eden—oh no! But go thy way," he exclaimed, raising his voice, "thou floating synagogue of Satan! And that puts me in mind of a story that happened near about where we are now riding. They had a great deal of money, all in silver, packed upon mules, for in them days we had n't any of this nasty paper money. I mind the time when tobacco was a legal tender, and 'coon-skins passed currenter than bank notes does now. In them days, if a man got into a chunk of a fight with his neighbour, a lawyer would clear him for half a dozen muskrat skins, and the justice and constable would have scorned to take a fee, more than just a treat or so.

But you know all that—so I'll tell my tale out, though I reckon you've heard it before? There was no chance to escape with their loaded mules; so they unloadened them, and buried the money somewhere among these rocks; and then being light, made their escape. So far, the old settlers all agree; but then some say that the Indians pursued on after them, a great way into Kentucky, and killed them all; others say that they finally escaped, the fact is, that the people never came back after the money, and it is supposed that it lies hid somewhere about here to this day.

Many a chap has sweated among these rocks by the hour. Only a few years ago, a great gang of folks came out of Kentucky, and dug all around here, as if they were going to make a crop; but to no purpose. They never come out boldly into the open field, and take a fair fight, fist and skull, as Christians do; but are always sneaking about in the bushes, studying out some devilment. The traders and hunters understand them perfectly well; the Indians and they are continually practising devices on each other.

Many a trick I've played on them, and they have played me as many. Now it seems to me to be nateral —just as plain as if I was on the ground and saw it, that them traders should have made a sham of burying money, and run off while the Indians were looking for it.

www.farmersmarketmusic.com, It's personal

Johnson, in broaching this subject, had not been aware of the interest it possessed in the mind of his friend. The fact was, that Bangs in his visits to this country had frequently heard the report alluded to, and it was precisely suited to operate upon his credulous and enthusiastic mind. At first he pondered on it as a matter of curiosity, until it fastened itself upon his imagination.

In his long and lonesome journeys, when he rode for whole days without seeing a human face, or habitation, he amused himself in calculating the probable amount of the buried treasure. The first step was to fix in his own mind the number of mules, and as the tradition varied from one to thirty , he prudently adopted the medium between these extremes. He found some difficulty in determining the burthen of a single mule, but to fix the number of dollars which would be required to make up that burthen, was impossible, because the worthy divine was so little acquainted with money, as not to know the weight of a single coin.

For the first time in his life he lacked arithmetic, and found himself in a strait, in which he conceived that it might be prudent to take the counsel of a friend. Near the residence of the reverend man dwelt an industrious pedagogue. He was a tall, sallow, unhealthy looking youth, with a fine clear blue eye, and a melancholy countenance, which at times assumed a sly sarcastic expression that few could interpret. In the winter, when the farmers' children had a season of respite from labour, he diligently pursued his vocation.

The Golden Pen

In the summer he strolled listlessly about the country, sometimes roaming the forest with his rifle, sometimes eagerly devouring any book that might chance to fall into his hands. Between him and the preacher there was little community of sentiment; yet they were often together: They never met without disputation, yet they always parted in kindness. The preacher, instead of wondering, with the rest of the neighbours, how "one small head could carry all he knew," derided the acquirements of his friend as worse than vanity; and the latter respectfully, but stoutly, maintained the dignity of his profession.

It was not without many qualms of pride that the worthy father now sought the school-master, with the intention of gaining information which he knew not how to get from any other source. Having once made up his mind, he acted with his usual promptness, and unused to intrigue or circumlocution, proceeded directly to his point. Work it by the rule of three, and there is the answer. The preacher's eyes glistened as he saw the figures; a long deep groan such as he was in the habit of heaving upon all occasions, whether of joy or sorrow, burst involuntarily from him. Young man, the wealth of Solomon was nothing to this— yea, the treasures of Nebuchadnezzar were as dust in the balance compared with this hoard!

It was indeed a vast sum! He seemed to have opened his eyes upon a new world. He conjured up in his mind all the harm that a bad man might do with so much money; and trembled to think that any one individual might, by possibility, become master of a treasure so great, as to be fraught with destruction to its possessor, and danger to the whole community in which he lived. He thought of the luxury, the dissipation, the corruption, that it might lead to; and rising gradually to a climax, he adverted to the ruinous and dreadful consequences, if this wealth should fall into the hands of some weak minded, zealous man, who was misled by false doctrines: Turning from this picture, he reflected on the benefits which a good man might with all this money confer on his fellows.

Zedekiah, now it was that the tempter, who had been all along sounding thee at a distance, began to lay a regular siege to thy integrity! Now it was that he sought to creep into the breast, yea, into the very heart's core, of worthy Zedekiah! He had always been poor and contented. But age was now approaching, and he could fancy a train of wants attendant upon helpless decrepitude. He glanced at the tattered sleeve of his coat, and straightway the vision of a new suit of snuff-coloured broadcloath rose upon his mind.

He thought of his old wife who sat spinning in the chimney corner at home; she was lame, and almost blind, poor woman! In short, the Reverend Mr Bangs set his heart upon having the money. Such was the state of matters, when the conversation occurred which I have just related. It was again renewed at Johnson's house, that night, after a substantial supper, and ended as such conversations usually do, in confirming each party in his own opinion.

Indeed the old man had that day got, as he thought, a clue, which might lead to the wished for discovery. He had heard of an ancient dame, who many years before had dropped mysterious hints, which induced a belief that she knew more on this subject than she chose to tell. On the following morning, the preacher rose early, saddled his nag and rode forth in search of the old woman's dwelling, without apprising any one of his intention.

He soon found the spot, and the object of his search.

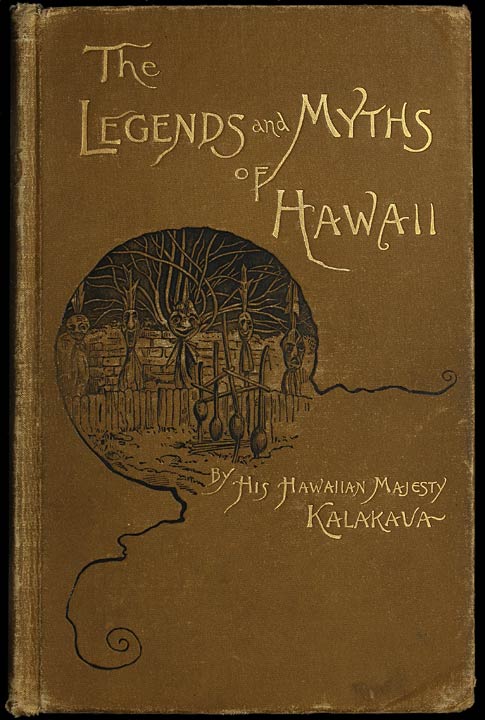

www.farmersmarketmusic.com: The Legend of the Scarlet Ravine and other Tales to Chill your Bones eBook: The Golden Pen, Mary Aris: Kindle Store. Legend of the Scarlet Ravine and Other Tales to Chill your Bones,are four bizarre and grizzling short tales to chill your bones on an autumn evening.

She was a poor, decrepid, superannuated virago, who dwelt in a hovel as crazy, as weatherbeaten, and as frail, as herself. She was crouched over the fire smoking a short pipe, and barely turned her head, as the reverend man seated himself on the bench beside her. The old man warmed his hands, stirred the fire with his stick, and being a bold man, advanced again to the charge.

The preacher mentioned his name, his vocation, and the object of his visit. She has written over a thousand poems. Melodies of the Heart is Mary's first published book featuring twenty-nine of her best poems on the subject of love. She lives in England with her husband, Alexander. Log In Sign Up Cart. Books by Mary Aris. Search Go More Detail. Against the admonition of Daniel Goode, the Magistrate, a The mob chases Anastasia deep into the heart of Epping Forest, stabbing her and her unborn child to death. Looking into their eyes with her emerald eyes, Anastasia places an evil curse on the Village—a curse so deadly that it wipes out half of Europe.

Legend of the Scarlet Ravine and Other Tales to Chill your Bones ,are four bizarre and grizzling short tales to chill your bones on an autumn evening. Once upon a time, in a far-away land lived an old king and his queen. I'm watching Switch at the moment. It's a cool new series about a coven of modern-day witches living in London.

I can't believe Halloween is nearly here.

I did a bit of ironing today and made six buttermilk pancakes for our breakfast tomorrow. I'm planning to relax tomorrow; perhaps watch some Halloween-themed DVD's and prerecorded movies. I'll be making popcorn either toni Explore Most Loved Sign up Sign in. Ghostly Cupcakes I made these ghostly cupcakes this afternoon.