Articles of Faith: (The Jewish Encyclopedia)

Contents:

But among the Tannaim and Amoraim this example of Philo found no followers, though many of their number were drawn into controversies with both Jews and non-Jews, and had to fortify their faith against the attacks of contemporaneous philosophy as well as against rising Christianity.

This particular scholarly style can be seen in the Jewish Encyclopedia's almost obsessive attention to manuscript discovery, manuscript editing and publication, manuscript comparison, manuscript dating, and so on; these endeavors were among the foremost interests of Wissenschaft scholarship. The points of agreement in these recent productions consist in the affirmation of the unity of God; the election of Israel as the priest people; the Messianic destiny of all humanity. We welcome suggested improvements to any of our articles. The Covenanters of Damascus. Judah Hadassi acknowledges that he had predecessors in this line, and mentions some of the works on which he bases his enumeration.

Only in a general way the Mishnah Sanh. Akiba would also regard as heretical the readers of —certain extraneous writings Apocrypha or Gospels —and persons that would heal through whispered formulas of magic. Abba Saul designated as under suspicion of infidelity those that pronounce the ineffable name of the Deity. By implication the contrary doctrine and attitude may thus be regarded as having been proclaimed as orthodox. On the other hand, Akiba himself declares that the command to love one's neighbor is the fundamental principle of the Law; while Ben Asai assigns this distinction to the Biblical verse, "This is the book of the generations of man" Gen.

The definition of Hillel the elder, in his interview with a would-be convert Shab. A teacher of the third Christian century, R.

Simlai, traces the development of Jewish religious principles from Moses with his commands of prohibition and injunction, through David, who, according to this rabbi, enumerates eleven; through Isaiah, with six; Micah, with three; to Habakkuk, who simply but impressively sums up all religious faith in the single phrase, "The pious lives in his faith" Mak.

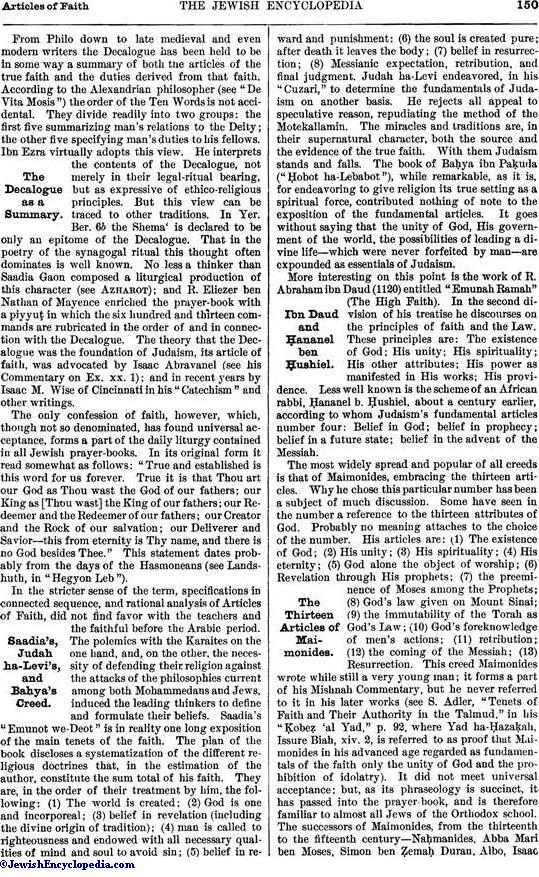

As the Halakah enjoins that one shall prefer death to an act of idolatry, incest, unchastity, or murder, the inference is plain that the corresponding positive principles were held to be fundamental articles of Judaism. From Philo down to late medieval and even modern writers the Decalogue has been held to be in some way a summary of both the articles of the true faith and the duties derived from that faith. They divide readily into two groups: Ibn Ezra virtually adopts this view. He interprets the contents of the Decalogue, not merely in their legal-ritual bearing, but as expressive of ethico-religious principles.

But this view can be traced to other traditions. That in the poetry of the synagogal ritual this thought often dominates is well known. No less a thinker than Saadia Gaon composed a liturgical production of this character see Azharot ; and R. The theory that the Decalogue was the foundation of Judaism, its article of faith, was advocated by Isaac Abravanel see his Commentary on Ex.

Wise of Cincinnati in his "Catechism" and other writings. The only confession of faith, however, which, though not so denominated, has found universal acceptance, forms a part of the daily liturgy contained in all Jewish prayer-books. In its original form it read somewhat as follows: True it is that Thou art our God as Thou wast the God of our fathers; our King as [Thou wast] the King of our fathers; our Redeemer and the Redeemer of our fathers; our Creator and the Rock of our salvation; our Deliverer and Savior—this from eternity is Thy name, and there is no God besides Thee.

In the stricter sense of the term, specifications in connected sequence, and rational analysis of Articles of Faith, did not find favor with the teachers and the faithful before the Arabic period. The polemics with the Karaites on the one hand, and, on the other, the necessity of defending their religion against the attacks of the philosophies current among both Mohammedans and Jews, induced the leading thinkers to define and formulate their beliefs. Saadia's "Emunot we-Deot" is in reality one long exposition of the main tenets of the faith.

The plan of the book discloses a systematization of the different religious doctrines that, in the estimation of the author, constitute the sum total of his faith.

They are, in the order of their treatment by him, the following: Judah ha-Levi endeavored, in his "Cuzari," to determine the fundamentals of Judaism on another basis. He rejects all appeal to speculative reason, repudiating the method of the Motekallamin.

ARTICLES OF FAITH - www.farmersmarketmusic.com

The miracles and traditions are, in their supernatural character, both the source and the evidence of the true faith. With them Judaism stands and falls.

It goes without saying that the unity of God, His government of the world, the possibilities of leading a divine life—which were never forfeited by man—are expounded as essentials of Judaism. More interesting on this point is the work of R. In the second division of his treatise he discourses on the principles of faith and the Law.

Moses Maimonides

Belief in God; belief in prophecy; belief in a future state; belief in the advent of the Messiah. The most widely spread and popular of all creeds is that of Maimonides, embracing the thirteen articles. Why he chose this particular number has been a subject of much discussion. Some have seen in the number a reference to the thirteen attributes of God. Probably no meaning attaches to the choice of the number.

They would contain scientific and unbiased articles on ancient and modern Jewish culture. This proposal received good press coverage and interest from the Brockhaus publishing company. Initially believing that American Jews could do little more than provide funding for his project, Singer was impressed by the level of scholarship in the United States.

His radical ecumenism and opposition to orthodoxy upset many of his Jewish readers; nevertheless he attracted the interest of publisher Isaac K. Funk , a Lutheran minister who also believed in integrating Judaism and Christianity. Funk agreed to publish the encyclopedia on the condition that it remain unbiased on issues which might seem unfavorable for Jews.

Reward Yourself

Publication of the prospectus in created a severe backlash, including accusations of poor scholarship and of subservience to Christians. Despite their reservations about Singer, rabbi Gustav Gottheil and Cyrus Adler agreed to join the board, followed by Morris Jastrow , then Frederick de Sola Mendes and two published critics of the project: Kauffmann Kohler and Gotthard Deutsch. Theologian and Presbyterian minister George Foot Moore was added to the board for balance.

Soon after work started, Moore withdrew and was replaced by Baptist minister Crawford Toy. Last was added the elderly Marcus Jastrow , mostly for his symbolic imprimatur as America's leading Talmudist. The editors plunged into their enormous task and soon identified and solved some inefficiencies with the project. Article assignments were shuffled around and communication practices were streamlined. Joseph Jacobs was hired as a coordinator. He also wrote four hundred articles and procured many of the encyclopedia's illustrations.

Herman Rosenthal , an authority on Russia, was added as an editor. Louis Ginzberg joined the project and later became head of the rabbinical literature department. The board naturally faced many difficult editorial questions and disagreements.

- ARTICLES OF FAITH:.

- Using Your Imagination;

- Famous Deaths.

- Join Kobo & start eReading today?

- Candide.

- Schmutz (Littérature) (French Edition).

Singer wanted specific entries for every Jewish community in the world, with detailed information about, for example, the name and dates of the first Jewish settler in Prague. Conflict also arose over what types of bible interpretation should be included, with some editors fearing that Morris Jastrow's involvement in " higher criticism " would lead to unfavorable treatment of scripture. The scholarly style of the Jewish Encyclopedia is very much in the mode of the Wissenschaft des Judentums "Jewish studies" , an approach to Jewish scholarship and religion that flourished in 19th-century Germany; indeed, the Encyclopedia may be regarded as the culmination of this movement, which sought to modernize scholarly methods in Jewish research.

In the 20th century, the movement's members dispersed to Jewish Studies departments in the United States and Israel.

The scholarly authorities cited in the Encyclopedia—besides the classical and medieval exegetes —are almost uniformly Wissenschaft figures, such as Leopold Zunz , Moritz Steinschneider , Solomon Schechter , Wilhelm Bacher , J. Essays and Poems On Jesus Christ. A Doubter's Guide to the Ten Commandments. Confession of a Roman Catholic.

Navigation menu

An Examination of the Pearl. The Covenanters of Damascus. Sabbath Keepers - Answering the Arguments. The Wisdom of the Desert. Living with Confidence in a Chaotic World. Works of Archibald Alexander Hodge. Beyond the Worship Wars.

No Fixed Dogmas. In the same sense as Christianity or Islam, Judaism can not be credited with the possession of Articles of Faith. Many attempts have indeed. In Biblical and rabbinical literature, and hence in the Jewish conception, "faith" (faith) receive the meaning of dogmatic belief, on which see Articles of Faith. K.

Your God Is Too Small. The Bondage of the Will, Handbook for Readers at Mass. The Mark of the Beast Is Coming. An Introduction to Covenant Theology. God's Word in Your Mouth. Can God Be Trusted? The Sermon on the Mount through the Centuries. Prayer in the Trinity. On Prayer and Contemplation. Simple Thoughts in a complex world.

The Importance of Christian Scholarship. The Movement in Acts.