Cold Fusion Power for Everything: How Andrea Rossis E-Cat Could Change the World

Contents:

Cold fusion reactor independently verified, has 10,000 times the energy density of gas

Don't you think that, with regard to the scientific praxis and credits, it would be more appropriate to rely on the university than on an individual researcher? In summary, I don't intend to give any other dimostrative test: We are selling plants to customers who run their own tests and decide whether to buy the E-Cat or not relying on their results: Meanwhile, the university of Bologna will take scrupulous care of the scientific work. If the DECC, or any other public or private organization, has taken an interest in this technology, I suggest them to get in touch and discuss any possible business agreement with me.

Thank you for your support and your balance in pointing out to me such important and sensitive questions. Best regards Andrea Rossi. Che giornata ricca di lanci spaziali! Sindrome da fatica cronica e sistema immunitario. He clamped it again. He decoupled the E-Cat's power cord with a theatrical flourish and darted over to a laptop. The computer logged temperature data from a probe stuck into the top of the E-Cat. The E-Cat was running in what Rossi called "self-sustained mode," implying that the reaction occurring inside of it—whatever that reaction might be—generated enough excess heat to keep itself going.

It's impossible to say what produced the heat. Even if Rossi was showing me an accurate calorimeter reading, it wouldn't be enough to conclude that his machine contained a nuclear reaction. A device the approximate size and volume of the 10kW E-Cat module would have to operate in self-sustained mode for at least one week to rule out the possibility of an exothermic chemical reaction.

Rossi jutted his square chin and clasped his hands behind his back. This is our revolution. Rossi's past demonstrations were tightly controlled affairs. A month after the botched investor demo, when he debuted his 1-megawatt mW E-Cat for the public, he made people stand outside in the cold, inviting them in one at a time for a five-minute glimpse. So I was surprised when he left me alone to poke around his warehouse for hours. It was stifling inside, and occasionally Rossi came out of his office to offer me something to drink or to steady a stepladder as I teetered on the top rung taking photos.

I crawled around every inch of a big blue shipping container that housed linked E-Cat modules—one of Rossi's 1mW plants.

- Jazz Maynard - Tome 1 - Home Sweet Home (French Edition).

- Christmas Miracle at the Mall.

- Diamond Jubilee at Riverside!

I'd seen pictures of a similar unit on the Web, but Rossi said that one had been sold to a "military concern. After I finished clambering around the plant, I met Rossi in his office, a small gray room decorated only by a wall calendar featuring a blonde woman wearing a bikini. Has been pretty final. That very morning, he said, the Swiss industrial certification firm SGS had completed safety tests of the 1mW plant. He didn't have the actual paper certificate from SGS to show me he expected to receive it by mail in August , but he did have new customers—sort of.

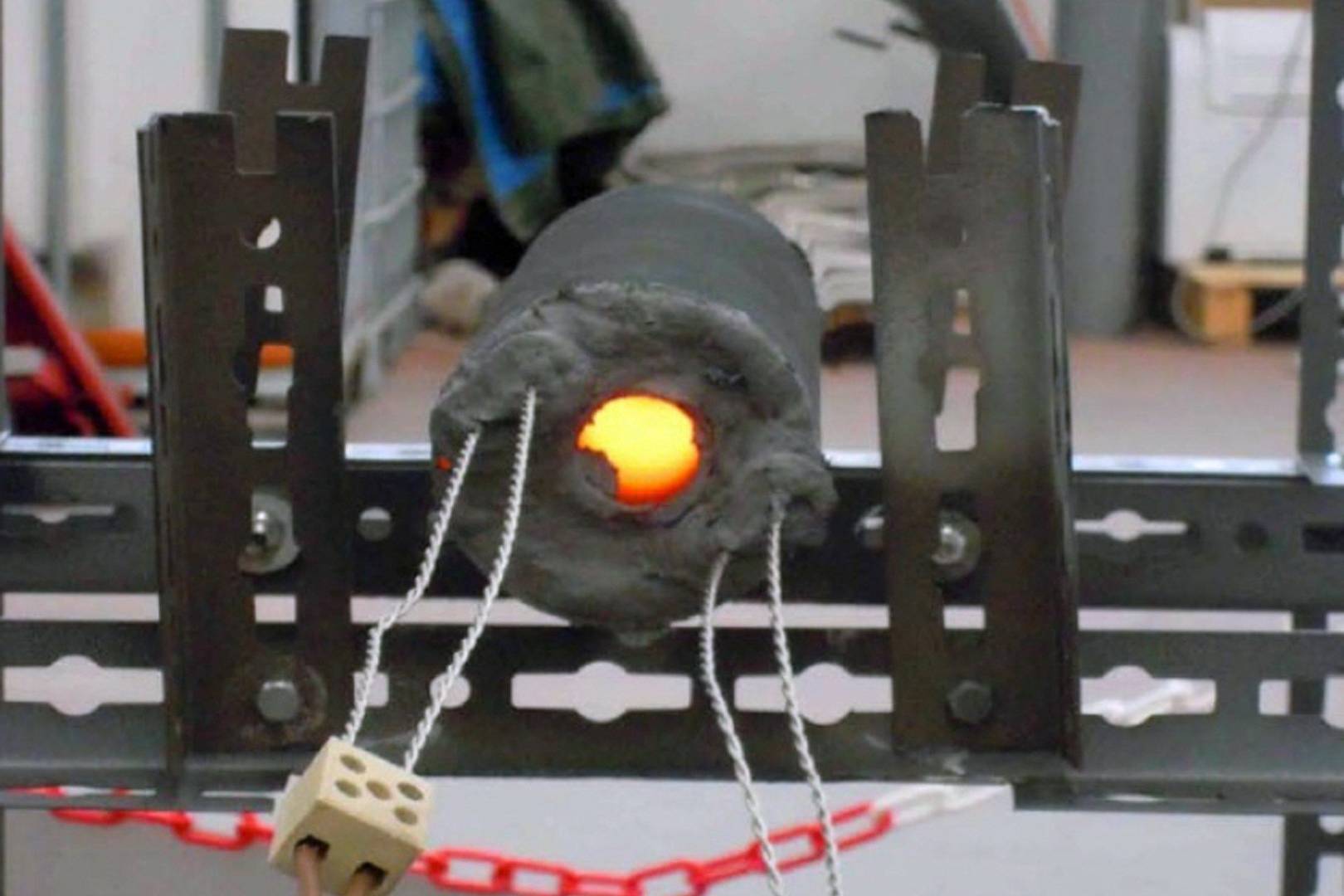

Two more plants would be going out the door in September. Rossi in his Bologna warehouse with a kilowatt E-Cat module. He has been criticized in the past for not unplugging his machine during demos. This seemed unlikely, but it wasn't impossible. Even if SGS really had certified that the E-Cat is safe, no independent third party has verified that it actually works. Not that Rossi hasn't had that opportunity. Both times he withdrew. They assured him they wouldn't reveal any proprietary secrets.

When I asked Rossi about these aborted attempts at independent verification, he cut me off. I pressed him for details. For the first time during our conversation, in which he had answered every question with polite candor and humor, Rossi faltered. He offered names of people involved in the test, their affiliations and areas of expertise, and trailed off into silence as if he was unaccustomed to giving specifics on the fly.

The dry rattle of cicadas filtered through the transom. Everything was off the record, Rossi said, apologizing for his "Freudian lapses.

Latest News

I asked to see test data, but he declined under the terms of the nondisclosure agreement he'd signed giving the "important university" exclusive right to publish the report—perhaps in the scientific journal Nature , he suggested. I never discovered who ratted me out to Rossi, but I managed to reschedule a visit with the ringleader of the skeptics gang, Ugo Bardi.

Bardi is a professor of physical chemistry at the University of Florence. In he was doing research in electrochemistry at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California when Fleischmann and Pons announced their discovery of cold fusion. The news thrilled him, but his research director dismissed it as a hoax. Bardi set out to replicate the Fleischmann-Pons effect anyway. His experiment didn't work, and like thousands of other scientists who also tried and failed, Bardi promptly forgot about cold fusion.

Then Rossi began stirring things up in early Bardi and his colleagues believed there was something to the story. You have an atomic weapon. It wasn't, however, a cogent argument against low-energy nuclear reactions, which shouldn't at least according to the theories circulating in the LENR world produce thermonuclear levels of radiation.

Buy Cold Fusion Power for Everything: How Andrea Rossi's E-Cat Could Change the World: Read 4 Books Reviews - www.farmersmarketmusic.com third parties concludes Rossi's E-Cat delivers unbelievable power output. Of Rossi's E-Cat Cold Fusion Device: Maybe The World Will Change After All Andrea Rossi, and his E-Cat project, a device that produces heat.

But to Bardi this was a distinction without a difference. It's all cold fusion to him. He didn't care how many researchers said they had produced results. These people, he says, are deluding themselves. Sepia photographs of famous La Sapienza scientists hung on the wall. Every time I tendered a question, Enrico Fermi glowered at me in the dim light. I asked Ruocco if he had tried to replicate the Fleischmann-Pons effect.

He shook his head no. I began to ask if he was aware of the work that many LENR scientists—. Ruocco raised his hand. Mostly independent "garage research men" worked in LENR, he insisted, not scientists, and that was okay by him as long as they didn't waste public money on their experiments or waste his time by asking him to disprove their results.

Let's talk about some of those results, I said, playing devil's advocate. I threw pitch after pitch in support of LENR, and they politely, but firmly, swatted them away. A "patchwork" of theories that were "locally reasonable" but wrong as a whole. Yet as confident as they were when we were talking about theory, Ruocco and Polosa didn't refute specific LENR experiments. They didn't even seem to be aware of them.

At this point, you have to look at the quality of the people. If "stellar" physicists like Carlo Rubbia, a Nobel prize winner, godfather of CERN's Large Hadron Collider, and supporter of cold-fusion research in Italy, couldn't prove cold fusion was real, what chance did "garage research men" have?

As I walked back to the train station, I recalled something Ugo Bardi had said, that cold fusion was a "clash of absolutes. Each believes the other is wrong; each believes the empirical evidence is on his side. In this rigid context, Rossi's erratic behavior had a shrewd logic to it. The only thing that kept him in the game was his canny ability to straddle the intersection of science and belief. Two weeks after I met with Rossi, he e-mailed me a page "technical report" documenting a test that was performed on the Hot Cat.

The report contained photographs of the Hot Cat and calculations of its thermal energy output. The data was "very confidential," Rossi wrote, but he gave me permission to "say that third-party validation test has been made with those results. Days later he dropped hints on his blog that parts of the report "eventually will be published in a scientific magazine. It seemed like a clumsy attempt to launder his test data in this magazine. Instead, I removed all identifying information and sent the report to an expert at NASA experienced in conducting third-party validation tests.

While the NASA expert didn't entirely refute the report's findings, the test protocols and conclusions didn't meet the standards of a credible third-party evaluation. The outcome wasn't surprising, but I was disappointed nonetheless. Some small part of me wanted Rossi to prove my suspicions wrong.

The director of the Hot Cat test, a retired colonel and friend of Rossi's, leaked the test results on the Web a week after Rossi sent them to me. The enthusiastic colonel "could not help to talk about this event and the remarkable results," Rossi said on his blog. Rossi used the occasion to make another big announcement: The University of Bologna would conduct a new independent test of the Hot Cat and publish the results in October.

When I contacted Dario Braga, vice rector for research at the University of Bologna, he unequivocally denied any official relationship between the university and Rossi. Rossi in a formally correct way," Braga said. Rossi can say this. If history is any guide, no such report would be issued. Rossi will reset the goalposts—the only thing he does with any consistency—and forestall his day of reckoning for another few months, and then another few months after that, until finally he disappears from the stage in a puff of smoke, taking his black box with him. He picked me up at the train station, drove me to the INFN complex in Frascati, handed my passport to the armed guards, and headed to a white metal shed set on a windy hilltop next to a row of olive trees.

Celani manufactured his own LENR cells, and the floor was littered with metal shavings. Dozens of glass cylinders of every size and shape cluttered the tabletops. He pointed to a narrow glass cylinder that resembled an oversize hypodermic needle resting on its side. It had been running for six weeks straight, Celani said. He called it his "special reactor. It was difficult to fathom that nuclear reactions thousands of times more energetic than any known chemical reaction were occurring on the hair-thin wire coiled inside the gas-filled cylinder.

But in the end, most of these researchers are just looking for an explanation and would be happy if even a modest amount of heat generated turns out to be useful in some way. Nagel , an electrical and computer engineering professor at George Washington University and a former research manager at the Naval Research Laboratory. The original branch of the field focuses on infusing deuterium into a palladium electrode by turning on the power, Nagel explains.

Researchers have reported such electrochemical systems that can output more than 25 times as much energy as they draw. The other main branch of the field uses a nickel-hydrogen setup, which can produce greater than times as much energy as it uses. Nagel says the LENR field continues to grow internationally, and the biggest hurdles remain inconsistent results and lack of funding.

For example, some researchers report that a certain threshold must be reached for a reaction to start. The reaction may require a minimum amount of deuterium or hydrogen to get going, or the electrode materials may need to be prepared with a specific crystallographic orientation and surface morphology to trigger the process.

The latter is a common issue with heterogeneous catalysts used in petroleum refining and petrochemical production.

A new theory

Nagel acknowledges that the business side of LENR has had problems too: In , Rossi and his colleagues announced at a press conference in Bologna, Italy, that they had built a tabletop reactor, called the Energy Catalyzer, or E-Cat, that produces excess energy via a nickel-catalyzed process.

Rossi posits that his E-Cat features a self-sustaining process in which electrical power input initiates fusion of hydrogen and lithium from a powdery mixture of nickel, lithium, and lithium aluminum hydride to form a beryllium isotope. Rossi says no waste is created in the process, and no radiation is detected outside the apparatus.

One reason many people are having trouble believing Rossi is his checkered past. In Italy, he was convicted of white-collar criminal charges related to his earlier business ventures. Rossi says those convictions are behind him and he no longer wants to talk about them.

Rossi writes on blog: What is most disappointing is the abundance of emotional reactions that have been precluding engaging the scientific method. We have presently plants working in the USA, in Italy and in other locations. If somebody has a technology able to compete, the competition will not be on the blogs, but on the market. Rossi files application for second U. Our customers will buy a working device; if it didn't work, they wouldn't buy it.

He also once had a contract to make heat-generating devices for the U. But the delivered devices did not work according to specifications. In , Rossi announced completion of a 1-MW system that could be used to heat or power large buildings. But neither the factory nor the household units have materialized.

In the meantime, Industrial Heat and Leonardo have had a falling out, and both are now suing each other in court over violations of their agreement. Rossi continues his research and has announced development of other prototypes. But he gives away few details about what he is doing. The household devices are still waiting for safety certification, he notes.

Even if a device clears the hurdles of reproducibility and usefulness, he adds, its developers face an uphill battle of regulatory approval and customer acceptance. But Nagel remains optimistic. For that reason, Nagel has just outfitted a lab at George Washington to start a new line of nickel-hydrogen experiments.

Many of the researchers who continue to work on LENR are accomplished scientists and are now retired. Nuclear physicist Ludwik Kowalski, an emeritus professor at Montclair State University, agrees cold fusion got off to the wrong start. Whether or not the claims of LENR researchers are valid, Kowalski believes a clear yes or no answer is still worth seeking. Even if Kowalski gets a yes to his question and LENR researcher claims are validated, the path to commercialization is fraught with challenges. Not all start-up companies, even ones with sound technology, are successful for reasons that are not scientific in nature: For example, consider Sun Catalytix.