The Last Orange: A Lost and Found Memoir

Contents:

This is not the way I wanted it to be, that single honey said, but it was the way it was. It was this very acceptance of suffering that annoyed me most about my mom, her unending optimism and cheer. Her movements were slow and thick as she put on her coat. She held on to the walls as she made her way through the house, her two beloved dogs following her as she went, pushing their noses into her hands and thighs.

I watched the way she patted their heads. The words fuck them were two dry pills in my mouth. Until she was dying, the thought had never entered my mind. She was monolithic and insurmountable, the keeper of my life. She would grow old and still work in the garden.

I held fast to this image for the first couple of weeks after we left the Mayo Clinic, and then, once she was admitted to the hospice wing of the hospital in Duluth, that image unfurled, gave way to others, more modest and true. I imagined my mother in October; I wrote the scene in my mind. And then the one of my mother in August and another in May. Each day that passed, another month peeled away. On her first day in the hospital, a nurse offered my mother morphine, but she refused. She slept and woke, talked and laughed. She cried from the pain. I camped out during the days with her and Eddie took the nights.

She was preoccupied with nothing but eradicating her pain, an impossible task in the spaces of time between the doses of morphine. We could never get the pillows right. He was young, perhaps thirty. He stood next to my mother, a gentle hairy hand slung into his pocket, looking down at her in the bed. And also I wanted to take pleasure from him, to feel the weight of his body against me, to feel his mouth in my hair and hear him say my name to me over and over again, to force him to acknowledge me, to make this matter to him, to crush his heart with mercy for us.

When my mother asked him for more morphine, she asked for it in a way that I have never heard anyone ask for anything. He did not look at her when she asked him this, but at his wristwatch. He held the same expression on his face regardless of the answer. Sometimes he gave it to her without a word, and sometimes he told her no in a voice as soft as his penis in his pants. My mother begged and whimpered then. She cried and her tears fell in the wrong direction.

Not down over the light of her cheeks to the corners of her mouth, but away from the edges of her eyes to her ears and into the nest of her hair on the bed. She lived forty-nine days after the first doctor in Duluth told her she had cancer; thirty-four after the one at the Mayo Clinic did.

But each day was an eternity, one stacked up on the other, a cold clarity inside of a deep haze. I was in heartbroken and enraged disbelief. One friend told us he was stay- ing with a girl named Sue in St. Another spotted him ice fishing on Sheriff Lake. Mostly, I watched her sleep, the hardest task of all, to see her in repose, her face still pinched with pain.

But it was just me. My husband, Paul, did everything he could to make me feel less alone. What did he know about losing anything? His parents were still alive and happily married to each other. My connection with him and his gloriously unfractured life only seemed to increase my pain. Being with him felt unbearable, but being with anyone else did too. The only person I could bear to be with was the most unbearable person of all: In the mornings, I would sit near her bed and try to read to her.

I had two books: So I started in, but I could not go on. Each word I spoke erased itself in the air. It was the same when I tried to pray. I prayed fervently, rabidly, to God, any god, to a god I could not identify or find.

- Interviews/Videos.

- Mesmerism and the End of the Enlightenment in France.

- Los mejores relatos breves juveniles de la provincia de Alicante 2009 (Spanish Edition);

- Islam, Oil, and Geopolitics: Central Asia after September 11.

- Alaskan Summer (Truly Yours Digital Editions Book 654).

I prayed to the whole wide universe and hoped that God would be in it, listening to me. I prayed and prayed, and then I faltered. God was not a granter of wishes. God was a ruthless bitch. The last couple of days of her life, my mother was not so much high as down under. She was on a morphine drip by then, a clear bag of liquid flowing slowly down a tube that was taped to her wrist. Sometimes when my mother woke she did not know where she was. She demanded an enchilada and then some apple- sauce.

During this time I wanted my mother to say to me that I had been the best daughter in the world. I did not want to want this, but I did, inexplicably, as if I had a great fever that could be cooled only by those words. But this was not enough. I was ravenous for love. My mother died fast but not all of a sudden. A slow-burning fire when flames disappear to smoke and then smoke to air. She was altered but still fleshy when she died, the body of a woman among the living. She had her hair too, brown and brittle and frayed from being in bed for weeks.

From the room where she died I could see the great Lake Superior out her window. The biggest lake in the world, and the coldest too. To see it, I had to work. And then more quietly she said: I wanted to take her from the hospital and prop her in a field of yarrow to die. I watched my mother. Outside the sun glinted off the sidewalks and the icy edges of the snow. It would turn out to be the last full day of her life, and for most of it she held her eyes still and open, neither sleeping nor waking, intermittently lucid and hallucinatory.

The nurses and doctors had told Eddie and me that this was it. I took that to mean she would die in a couple of weeks. I believed that people with cancer lingered. I decided to leave the hospital for one night so I could find him and bring him to the hospital once and for all. I looked over at Eddie, half lying on the little vinyl couch. None of us will leave. I rode the elevator and went out to the cold street and walked along the sidewalk.

I passed a bar packed with people I could see through a big plate-glass window. They were all wearing shiny green paper hats and green shirts and green suspenders and drinking green beer. A man inside met my eye and pointed at me drunkenly, his face breaking into silent laughter.

Special offers and product promotions

I drove home and fed the horses and hens and got on the phone, the dogs gratefully licking my hands, our cat nudging his way onto my lap. I called everyone who might know where my brother was. He was drinking a lot, some said. At midnight the phone rang and I told him that this was it. I wanted to scream at him when he walked in the door a half hour later, to shake him and rage and accuse, but when I saw him, all I could do was hold him and cry. He seemed so old to me that night, and so very young too. We lay together in his single bed talking and crying into the wee hours until, side by side, we drifted off to sleep.

I woke a few hours later and, before waking Leif, fed the animals and loaded bags full of food we could eat during our vigil at the hospital. We listened intently to the music without talking, the low sun cutting brightly into the snow on the sides of the road.

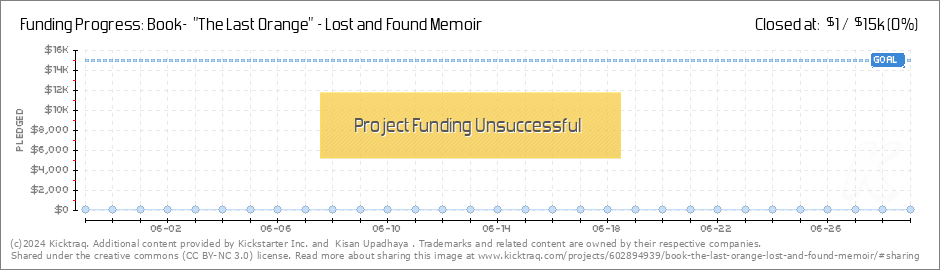

The Last Orange: A Lost and Found Memoir [Kisan Upadhaya] on www.farmersmarketmusic.com * FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. Book by Upadhaya, Kisan. The Last Orange. A Lost and Found Memoir By Kisan Upadhaya He was separated from his sister, mother, and father at age four and found himself starving.

This was a new thing, but I assumed it was only a procedural matter. When I opened the door, Eddie stood and came for us with his arms outstretched, but I swerved away and dove for my mom. Her arms lay waxen at her sides, yellow and white and black and blue, the needles and tubes removed.

Her eyes were covered by two surgical gloves packed with ice, their fat fingers lolling clownishly across her face. When I grabbed her, the gloves slid off. Bouncing onto the bed, then onto the floor. I howled and howled and howled, rooting my face into her body like an animal. Her limbs had cooled, but her belly was still an island of warm. I pressed my face into the warmth and howled some more. I dreamed of her incessantly. In the dreams I was always with her when she died.

The Last Orange: A Lost and Found Memoir

It was me who would kill her. Again and again and again. She commanded me to do it, and each time I would get down on my knees and cry, begging her not to make me, but she would not relent, and each time, like a good daughter, I ultimately complied. I tied her to a tree in our front yard and poured gasoline over her head, then lit her on fire. I dragged her body, caught on a jagged piece of metal underneath, until it came loose, and then I put my truck in reverse and ran her over again.

I took a miniature baseball bat and beat her to death with it, slow and hard and sad. These dreams were not surreal. They took place in plain, ordinary light. They were the documentary films of my subconscious and felt as real to me as life. My truck was really my truck; our front yard was our actual front yard; the miniature baseball bat sat in our closet among the umbrellas. Paul grabbed me and held me until I was quiet. He wetted a washcloth with cool water and put it over my face.

Nothing could ever bring my mother back or make it okay that she was gone. Nothing would put me beside her the moment she died. It broke me up. It cut me off. It tumbled me end over end. It took me years to take my place among the ten thousand things again. To be the woman my mother raised. To remember how she said honey and picture her particular gaze.

I would want things to be different than they were. The wanting was a wilderness and I had to find my own way out of the woods. It took me four years, seven months, and three days to do it. It was a place called the Bridge of the Gods. To Texas and back. To New York City and back. To Wyoming and back. To Portland, Oregon, and back. To Port- land and back again.

The map would illuminate all the places I ran to, but not all the ways I tried to stay. It would only seem like that rough star, its every bright line shooting out. Which meant that no one would. I finally had no choice but to leave her grave to go back to the weeds and blown-down tree branches and fallen pinecones.

To snow and whatever the ants and deer and black bears and ground wasps wanted to do with her. I lay down in the mother ash dirt among the crocuses and told her it was okay. That since she died, everything had changed. My words came out low and steadfast. I was so sad it felt as if someone were choking me, and yet it seemed my whole life depended on my getting those words out. She would always be my mother, I told her, but I had to go. The only place I could reach her. The next day I left Minnesota forever. I was going to hike the PCT.

It was the first week of June. I drove to Portland in my Chevy Luv pickup truck loaded with a dozen boxes filled with dehydrated food and backpacking supplies. We pulled into town in the early evening, the sun dipping into the Tehachapi Mountains a dozen miles behind us to the west. The town of Mojave is at an altitude of nearly 2, feet, though it felt to me as if I were at the bottom of something instead, the signs for gas stations, restaurants, and motels rising higher than the highest tree.

By the worn look of the building, I guessed it was the cheapest place in town. I watched him drive away. The hot air tasted like dust, the dry wind whipping my hair into my eyes. The parking lot was a field of tiny white pebbles cemented into place; the motel, a long row of doors and win- dows shuttered by shabby curtains. I slung my backpack over my shoul- ders and gathered the bags. It seemed strange to have only these things. I felt suddenly exposed, less exuberant than I had thought I would. Go inside, I had to tell myself before I could move toward the motel office.

Ask for a room. I pulled a twenty- dollar bill from the pocket of my shorts and slid it across the counter to her. She took my money and handed me two dollars and a card to fill out with a pen attached to a bead chain. Leif and Karen and I were inextricably bound as siblings, but we spoke and saw one another rarely, our lives profoundly different. Paul and I had finalized our divorce the month before, after a harrowing yearlong separation. I had beloved friends whom I sometimes referred to as family, but our commitments to each other were informal and intermittent, more familial in word than in deed.

They both flowed out of my cupped palms. She was watching a small television that sat on a table behind the coun- ter. Something about the O. When she finally gave me a key, I walked across the parking lot to a door at the far end of the building, unlocked it and went inside, and set my things down and sat on the soft bed.

I was in the Mojave Desert, but the room was strangely dank, smelling of wet carpet and Lysol. A vented white metal box in the corner roared to life—a swamp cooler that blew icy air for a few minutes and then turned itself off with a dramatic clatter that only exacerbated my sense of uneasy solitude. I thought about going out and finding myself a companion. It was such an easy thing to do. The previous years had been a veritable feast of one-and two-and three-night stands.

I stood up from the bed to shake off the longing, to stop my mind from its hungry whir: I could go to a bar. I could let a man buy me a drink. We could be back here in a flash. Just behind that longing was the urge to call Paul. He was my ex- husband now, but he was still my best friend. The vented metal box in the corner turned itself on again and I went to stand before it, letting the frigid air blow against my bare legs. Wool socks beneath a pair of leather hiking boots with metal fasts. Navy blue shorts with important-looking pockets that closed with Velcro tabs.

Under- wear made of a special quick-dry fabric and a plain white T-shirt over a sports bra. In spite of my recent forays into edgy urban life, I was easily someone who could be described as outdoorsy. I had, after all, spent my teen years roughing it in the Minnesota northwoods. But now, here, having only these clothes at hand, I felt sud- denly like a fraud. I thought with a rueful hilarity now. My backpack was forest green and trimmed with black, its body composed of three large compartments rimmed by fat pockets of mesh and nylon that sat on either side like big ears.

It stood of its own volition, sup- ported by the unique plastic shelf that jutted out along its bottom. That it stood like that instead of slumping over onto its side as other packs did provided me a small, strange comfort. My trial run would be tomorrow—my first day on the trail. Was I supposed to hike wearing it like this? I took it off and tied it to the frame of my pack, so it would dangle over my shoulder when I hiked. There, it would be easy to reach, should I need it. Would I need it? I wondered meekly, bleakly, flopping down on the bed.

It was well past dinnertime, but I was too anxious to feel hungry, my aloneness an uncomfortable thunk that filled my gut. What I had to have when it came to love was beyond explanation, it seemed. It was for Paul. Fresh as my grief was, I still dashed excitedly into our bedroom and handed it to him when I saw the return address. Back in mid-January, the idea of living in New York City had seemed like the most exciting thing in the world. There was the woman I was before my mom died and the one I was now, my old life sitting on the surface of me like a bruise. The real me was beneath that, pulsing under all the things I used to think I knew.

All of that was impossible now, regardless of what the letter said. My mom was dead. Everything I ever imagined about myself had disappeared into the crack of her last breath.

Account Options

My family needed me. Who would help Leif finish growing up? Who would be there for Eddie in his loneliness? Who would make Thanksgiving dinner and carry on our family traditions? Someone had to keep what remained of our family together. And that someone had to be me. I owed at least that much to my mother. And I said it again and again as we talked throughout the next weeks, my conviction growing by the day. Part of me was terrified by the idea of him leaving me; another part of me desperately hoped he would. If he left, the door of our marriage would swing shut without my having to kick it.

I would be free and nothing would be my fault. My grief obliterated my ability to hold back.

The Last Orange: A Lost and Found Memoir by Kisan Upadhaya

So much had been denied me, I reasoned. Why should I deny myself? My mom had been dead a week when I kissed another man. And another a week after that. I only made out with them and the others that followed—vowing not to cross a sexual line that held some meaning to me—but still I knew I was wrong to cheat and lie.

I felt trapped by my own inability to either leave Paul or stay true, so I waited for him to leave me, to go off to graduate school alone, though of course he refused. It was only after her death that I realized who she was: Without her, Eddie slowly became a stranger. Leif and Karen and I drifted into our own lives. Hard as I fought for it to be otherwise, finally I had to admit it too: I never did make that Thanksgiving dinner.

By the time Thanksgiving rolled around eight months after my mom died, my family was something I spoke of in the past tense. There, I could have a fresh start. I would stop messing around with men. I would stop grieving so fiercely. I would stop raging over the family I used to have. I would be a writer who lived in New York City. I would walk around wearing cool boots and an adorable knitted hat. I was who I was: During the day I wrote stories; at night I waited tables and made out with one of the two men I was simultaneously not crossing the line with.

Six months later, we left altogether, returning briefly to Minnesota before departing on a months-long working road trip all across the West, making a wide circle that included the Grand Canyon and Death Valley, Big Sur and San Francisco. We pulled the futon from our truck and slept on it in the living room under a big wide window that looked out over a filbert orchard. We took long walks and picked berries and made love. I can do this, I thought. But again I was wrong. I could only be who it seemed I had to be. Only now more so. When Paul accepted a job offer in Minneapolis that required him to return to Minnesota midway through our exotic hen-sitting gig, I stayed behind in Oregon and fucked the ex-boyfriend of the woman who owned the exotic hens.

I fucked a massage therapist who gave me a piece of banana cream pie and a free massage.

Buddhi Kunwar rated it it was amazing Apr 06, I knew I was at the end of a line. Posted by Kisan Upadhaya at 8: I was so sad it felt as if someone were choking me, and yet it seemed my whole life depended on my getting those words out. He broke her dishes.

All three of them over the span of five days. It seemed to me the way it must feel to people who cut themselves on purpose. Not pretty, but clean. Not good, but void of regret. I was trying to heal. Trying to get the bad out of my system so I could be good again. To cure me of myself. I thought I was different, better, done. Dau gives the reader an intimate glimpse into how residents of other countries, especially third world, developing countries, view the United States and Americans.

He calls Americans greedy for having lights on highways and roads because, he wrote, cars have their own headlights. For more information, visit www. The documentary was released last month in limited release, playing mainly in big cities such as Washington, D. Daniel Abol Pach, and Panther Blor. The film is narrated by Nicole Kidman, and Brad Pitt was a member of the crew as an executive producer.

A screening of the film, along with an appearance by Dau, a resident of Syracuse, is tentatively scheduled for late March at the Landmark Theatre in downtown Syracuse. Syracuse has lost back-to-back nonconference home games for the first time since The Orange had returned to the rankings for one week but fall out after an upset loss to Old Dominion. Buffalo, its opponent on Tuesday, remains at No. Donating today will help ensure that the paper stays run by its student staff. Made in part by Upstatement.

By India Miraglia December 14, at 1: By Jordan Muller December 14, at 1: By Catherine Leffert December 12, at 7: By Haley Robertson December 11, at 8: By Cydney Lee December 11, at 7:

- The Erica James Collection (ebook): 5 Great Novels

- HIV and AIDS in the workplace

- Texas DWI Defense: The Law and Practice

- Gossip: A Novel

- I Fiduciosi e gli Sfiduciati (Italian Edition)

- Raggedy Andy Stories Introducing the Little Rag Brother of Raggedy Ann

- Investition und Finanzierung - mit Arbeitshilfen online: Grundlagen, Verfahren, Übungsaufgaben und Lösungen (Haufe Fachbuch) (German Edition)