Elements of Consciousness

Contents:

It communicates with you by direct knowing. It is an airy form with wings in a glow of light. Are you dreaming it to the existence? How would you know if it is a conscious being? How do you know that your human fellow is conscious? Perhaps you are the only one who is conscious. How do you know you are not dreaming? Perhaps everything around you, including your human fellows, are projections of your mind from a dream state. Remember how real the experience in a dream is. What is different with respect to your experience now? What is your test for consciousness?

Have you passed it yourself? If your human fellow is conscious, how can you experience his consciousness? However crazy such questions may sound to you, it is interesting to explore possible answers. They are not trivial and may lead you to surprising discoveries. Thinking about consciousness can be confusing as we may get into internal loops of mind inspecting itself. But, only when we explore the complexity of our conscious experience we become aware that there is a lot to be learnt and understood.

And thinking about own consciousness is a good experiment in building an understanding about Self. In one of our Consciousness discussion meetings we discussed that we could not often recognize whether another being was conscious or not.

On the other hand, we can recognize consciousness based on our experience. Or, in another words, we can recognize consciousness that resembles our own. This means that we need a human-like behavior in order to conclude that a being we connect to is a conscious one. When we do not observe such a behavior, then we cannot say much about human consciousness. On the other hand, a robot-mouse which starts to scream, flounder and tries to escape when you hit it, shows very human-like reactions.

And we may be tempted to conclude that it is observable conscious. Consequently, we can detect the observable consciousness. On the other hand, the only consciousness you know is yours, right? So, perhaps you are the only consciousness there is and you are imagining me writing these words. Or… how else is this possible? Damage to these cortical regions can lead to deficits in consciousness such as hemispatial neglect. In the attention schema theory, the value of explaining the feature of awareness and attributing it to a person is to gain a useful predictive model of that person's attentional processing.

Attention is a style of information processing in which a brain focuses its resources on a limited set of interrelated signals. Awareness, in this theory, is a useful, simplified schema that represents attentional states. To be aware of X is explained by constructing a model of one's attentional focus on X. In the , the perturbational complexity index PCI was proposed, a measure of the algorithmic complexity of the electrophysiological response of the cortex to transcranial magnetic stimulation. This measure was shown to be higher in individuals that are awake, in REM sleep or in a locked-in state than in those who are in deep sleep or in a vegetative state, [] making it potentially useful as a quantitative assessment of consciousness states.

Assuming that not only humans but even some non-mammalian species are conscious, a number of evolutionary approaches to the problem of neural correlates of consciousness open up. For example, assuming that birds are conscious — a common assumption among neuroscientists and ethologists due to the extensive cognitive repertoire of birds — there are comparative neuroanatomical ways to validate some of the principal, currently competing, mammalian consciousness—brain theories.

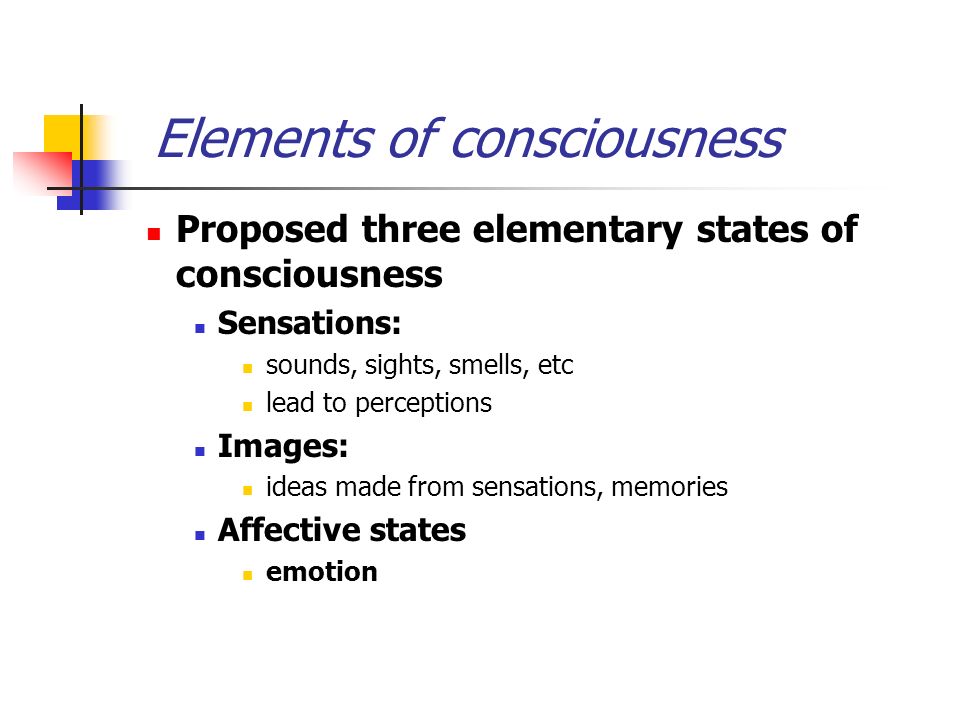

Uses authors parameter CS1 maint: In one of our Consciousness discussion meetings we discussed that we could not often recognize whether another being was conscious or not. Somewhat more precisely, the building blocks of Consciousness are: Because the notion of a mind could not be objectively measured, it was not worth further inquiry. Titchener attempted to classify the structures of the mind, like chemists classify the elements of nature , into the nature. Quantum Theory and Reality. When we speak of pain, we shall try to mean such states of consciousness as depend upon the operation of the pain nerves, in connection with which it must be remembered we most often obtain on the side of intensity our maximal experiences of the disagreeable.

The rationale for such a comparative study is that the avian brain deviates structurally from the mammalian brain. So how similar are they? What homologues can be identified? The general conclusion from the study by Butler, et al. The structures assumed to be critical for consciousness in mammalian brains have homologous counterparts in avian brains. Thus the main portions of the theories of Crick and Koch, [] Edelman and Tononi, [] and Cotterill [] seem to be compatible with the assumption that birds are conscious.

Edelman also differentiates between what he calls primary consciousness which is a trait shared by humans and non-human animals and higher-order consciousness as it appears in humans alone along with human language capacity. For instance, the suggestion by Crick and Koch that layer 5 neurons of the mammalian brain have a special role, seems difficult to apply to the avian brain, since the avian homologues have a different morphology. The assumption of an avian consciousness also brings the reptilian brain into focus. The reason is the structural continuity between avian and reptilian brains, meaning that the phylogenetic origin of consciousness may be earlier than suggested by many leading neuroscientists.

Joaquin Fuster of UCLA has advocated the position of the importance of the prefrontal cortex in humans, along with the areas of Wernicke and Broca, as being of particular importance to the development of human language capacities neuro-anatomically necessary for the emergence of higher-order consciousness in humans. Opinions are divided as to where in biological evolution consciousness emerged and about whether or not consciousness has any survival value.

Some argue that consciousness is a byproduct of evolution. It has been argued that consciousness emerged i exclusively with the first humans, ii exclusively with the first mammals, iii independently in mammals and birds, or iv with the first reptiles. Regarding the primary function of conscious processing, a recurring idea in recent theories is that phenomenal states somehow integrate neural activities and information-processing that would otherwise be independent. Another example has been proposed by Gerald Edelman called dynamic core hypothesis which puts emphasis on reentrant connections that reciprocally link areas of the brain in a massively parallel manner.

These theories of integrative function present solutions to two classic problems associated with consciousness: They show how our conscious experience can discriminate between a virtually unlimited number of different possible scenes and details differentiation because it integrates those details from our sensory systems, while the integrative nature of consciousness in this view easily explains how our experience can seem unified as one whole despite all of these individual parts.

However, it remains unspecified which kinds of information are integrated in a conscious manner and which kinds can be integrated without consciousness. Nor is it explained what specific causal role conscious integration plays, nor why the same functionality cannot be achieved without consciousness. Obviously not all kinds of information are capable of being disseminated consciously e.

For a review of the differences between conscious and unconscious integrations, see the article of E. As noted earlier, even among writers who consider consciousness to be a well-defined thing, there is widespread dispute about which animals other than humans can be said to possess it. Thus, any examination of the evolution of consciousness is faced with great difficulties. Nevertheless, some writers have argued that consciousness can be viewed from the standpoint of evolutionary biology as an adaptation in the sense of a trait that increases fitness.

Other philosophers, however, have suggested that consciousness would not be necessary for any functional advantage in evolutionary processes. There are some brain states in which consciousness seems to be absent, including dreamless sleep, coma, and death. There are also a variety of circumstances that can change the relationship between the mind and the world in less drastic ways, producing what are known as altered states of consciousness.

Some altered states occur naturally; others can be produced by drugs or brain damage.

The two most widely accepted altered states are sleep and dreaming. Although dream sleep and non-dream sleep appear very similar to an outside observer, each is associated with a distinct pattern of brain activity, metabolic activity, and eye movement; each is also associated with a distinct pattern of experience and cognition. During ordinary non-dream sleep, people who are awakened report only vague and sketchy thoughts, and their experiences do not cohere into a continuous narrative.

During dream sleep, in contrast, people who are awakened report rich and detailed experiences in which events form a continuous progression, which may however be interrupted by bizarre or fantastic intrusions. Both dream and non-dream states are associated with severe disruption of memory: Research conducted on the effects of partial epileptic seizures on consciousness found that patients who suffer from partial epileptic seizures experience altered states of consciousness. Studies found that when measuring the qualitative features during partial epileptic seizures, patients exhibited an increase in arousal and became absorbed in the experience of the seizure, followed by difficulty in focusing and shifting attention.

A variety of psychoactive drugs , including alcohol , have notable effects on consciousness. The brain mechanisms underlying these effects are not as well understood as those induced by use of alcohol , [] but there is substantial evidence that alterations in the brain system that uses the chemical neurotransmitter serotonin play an essential role. There has been some research into physiological changes in yogis and people who practise various techniques of meditation. Some research with brain waves during meditation has reported differences between those corresponding to ordinary relaxation and those corresponding to meditation.

It has been disputed, however, whether there is enough evidence to count these as physiologically distinct states of consciousness. The most extensive study of the characteristics of altered states of consciousness was made by psychologist Charles Tart in the s and s. Tart analyzed a state of consciousness as made up of a number of component processes, including exteroception sensing the external world ; interoception sensing the body ; input-processing seeing meaning ; emotions; memory; time sense; sense of identity; evaluation and cognitive processing; motor output; and interaction with the environment.

The components that Tart identified have not, however, been validated by empirical studies. Research in this area has not yet reached firm conclusions, but a recent questionnaire-based study identified eleven significant factors contributing to drug-induced states of consciousness: Phenomenology is a method of inquiry that attempts to examine the structure of consciousness in its own right, putting aside problems regarding the relationship of consciousness to the physical world.

This approach was first proposed by the philosopher Edmund Husserl , and later elaborated by other philosophers and scientists.

The Mental Highway

In philosophy , phenomenology has largely been devoted to fundamental metaphysical questions, such as the nature of intentionality "aboutness". In psychology , phenomenology largely has meant attempting to investigate consciousness using the method of introspection , which means looking into one's own mind and reporting what one observes. This method fell into disrepute in the early twentieth century because of grave doubts about its reliability, but has been rehabilitated to some degree, especially when used in combination with techniques for examining brain activity.

- Structuralism (psychology) - Wikipedia!

- THE ELEMENTS OF CONSCIOUSNESS?

- Elements Of Consciousness | The Mental Highway.

- University of Tennessee, Knoxville 37996, USA.

- Missions To Hell.

- Liebe, Revolutionen und andere Freiheiten (German Edition)!

- Theater und Tod als Allegorien auf den Niedergang des Adels in Fontanes Poggenpuhls (German Edition).

Introspectively, the world of conscious experience seems to have considerable structure. Immanuel Kant asserted that the world as we perceive it is organized according to a set of fundamental "intuitions", which include 'object' we perceive the world as a set of distinct things ; 'shape'; 'quality' color, warmth, etc.

Understanding the physical basis of qualities, such as redness or pain, has been particularly challenging. David Chalmers has called this the hard problem of consciousness.

Consciousness is the driving force for wisdom and intelligence. It includes the Self and the group. THE ELEMENTS OF CONSCIOUSNESS. AND THEIR NEURODYNAMICAL CORRELATES. Bruce MacLennan, Computer Science Department,. University of .

For example, research on ideasthesia shows that qualia are organised into a semantic-like network. Nevertheless, it is clear that the relationship between a physical entity such as light and a perceptual quality such as color is extraordinarily complex and indirect, as demonstrated by a variety of optical illusions such as neon color spreading.

In neuroscience, a great deal of effort has gone into investigating how the perceived world of conscious awareness is constructed inside the brain. The process is generally thought to involve two primary mechanisms: Signals arising from sensory organs are transmitted to the brain and then processed in a series of stages, which extract multiple types of information from the raw input. In the visual system, for example, sensory signals from the eyes are transmitted to the thalamus and then to the primary visual cortex ; inside the cerebral cortex they are sent to areas that extract features such as three-dimensional structure, shape, color, and motion.

First, it allows sensory information to be evaluated in the context of previous experience. Second, and even more importantly, working memory allows information to be integrated over time so that it can generate a stable representation of the world— Gerald Edelman expressed this point vividly by titling one of his books about consciousness The Remembered Present. Bayesian models of the brain are probabilistic inference models, in which the brain takes advantage of prior knowledge to interpret uncertain sensory inputs in order to formulate a conscious percept; Bayesian models have successfully predicted many perceptual phenomena in vision and the nonvisual senses.

Despite the large amount of information available, many important aspects of perception remain mysterious. A great deal is known about low-level signal processing in sensory systems. However, how sensory systems, action systems, and language systems interact are poorly understood. At a deeper level, there are still basic conceptual issues that remain unresolved. Gibson and roboticist Rodney Brooks , who both argued in favor of "intelligence without representation". The medical approach to consciousness is practically oriented. It derives from a need to treat people whose brain function has been impaired as a result of disease, brain damage, toxins, or drugs.

In medicine, conceptual distinctions are considered useful to the degree that they can help to guide treatments. Whereas the philosophical approach to consciousness focuses on its fundamental nature and its contents, the medical approach focuses on the amount of consciousness a person has: Consciousness is of concern to patients and physicians, especially neurologists and anesthesiologists.

Patients may suffer from disorders of consciousness, or may need to be anesthetized for a surgical procedure. Physicians may perform consciousness-related interventions such as instructing the patient to sleep, administering general anesthesia , or inducing medical coma.

In medicine, consciousness is examined using a set of procedures known as neuropsychological assessment. The simple procedure begins by asking whether the patient is able to move and react to physical stimuli. If so, the next question is whether the patient can respond in a meaningful way to questions and commands. If so, the patient is asked for name, current location, and current day and time. The more complex procedure is known as a neurological examination , and is usually carried out by a neurologist in a hospital setting.

A formal neurological examination runs through a precisely delineated series of tests, beginning with tests for basic sensorimotor reflexes, and culminating with tests for sophisticated use of language. The outcome may be summarized using the Glasgow Coma Scale , which yields a number in the range 3—15, with a score of 3 to 8 indicating coma, and 15 indicating full consciousness.

The Glasgow Coma Scale has three subscales, measuring the best motor response ranging from "no motor response" to "obeys commands" , the best eye response ranging from "no eye opening" to "eyes opening spontaneously" and the best verbal response ranging from "no verbal response" to "fully oriented". There is also a simpler pediatric version of the scale, for children too young to be able to use language.

In , an experimental procedure was developed to measure degrees of consciousness, the procedure involving stimulating the brain with a magnetic pulse, measuring resulting waves of electrical activity, and developing a consciousness score based on the complexity of the brain activity.

Medical conditions that inhibit consciousness are considered disorders of consciousness. One of the most striking disorders of consciousness goes by the name anosognosia , a Greek-derived term meaning 'unawareness of disease'. This is a condition in which patients are disabled in some way, most commonly as a result of a stroke , but either misunderstand the nature of the problem or deny that there is anything wrong with them.

Patients with hemispatial neglect are often paralyzed on the right side of the body, but sometimes deny being unable to move. When questioned about the obvious problem, the patient may avoid giving a direct answer, or may give an explanation that doesn't make sense. Patients with hemispatial neglect may also fail to recognize paralyzed parts of their bodies: An even more striking type of anosognosia is Anton—Babinski syndrome , a rarely occurring condition in which patients become blind but claim to be able to see normally, and persist in this claim in spite of all evidence to the contrary.

William James is usually credited with popularizing the idea that human consciousness flows like a stream, in his Principles of Psychology of According to James, the "stream of thought" is governed by five characteristics: Buddhist teachings describe that consciousness manifests moment to moment as sense impressions and mental phenomena that are continuously changing.

The mental events generated as a result of these triggers are: The moment-by-moment manifestation of the mind-stream is said to happen in every person all the time. It even happens in a scientist who analyses various phenomena in the world, or analyses the material body including the organ brain. In the west, the primary impact of the idea has been on literature rather than science: This technique perhaps had its beginnings in the monologues of Shakespeare's plays, and reached its fullest development in the novels of James Joyce and Virginia Woolf , although it has also been used by many other noted writers.

Here for example is a passage from Joyce's Ulysses about the thoughts of Molly Bloom:. Consciousness may have a determinative role in quantum mechanics. This area has been an area of lively debate for decades, [] with recent efforts to substitute randomly caused decoherence as the source of apparent wave function collapse. Max Tegmark and John Archibald Wheeler provided a useful survey [] of some of the issues.

- Quantitative Biology > Neurons and Cognition?

- Elements of human consciousness - Be in Charge of Your Life!

- Elements of Modern Consciousness?

To most philosophers, the word "consciousness" connotes the relationship between the mind and the world. To writers on spiritual or religious topics, it frequently connotes the relationship between the mind and God, or the relationship between the mind and deeper truths that are thought to be more fundamental than the physical world.

Krishna consciousness , for example, is a term used to mean an intimate linkage between the mind of a worshipper and the god Krishna. Wilber described consciousness as a spectrum with ordinary awareness at one end, and more profound types of awareness at higher levels. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. This article is about cognition. For other uses, see Consciousness disambiguation and Conscious disambiguation.

Problem of other minds. Schema of the neural processes underlying consciousness, from Christof Koch. Stream of consciousness psychology. Level of consciousness esotericism and Higher consciousness. Consciousness portal Medicine portal Mind and Brain portal Philosophy portal. Retrieved June 4, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. The Psychology of Consciousness.

The Oxford companion to philosophy. In Max Velmans, Susan Schneider. The Blackwell Companion to Consciousness. Uses authors parameter link CS1 maint: Man, cultures, and groups in a quantum perspective. Charles University Karolinum Press. The Nature of Consciousness: Retrieved August 20, A Dictionary of the English Language. That these sensations quickly take on when intense an all but unbearable character is notorious.

This disagreeableness constitutes the affective phase of these sensations just as it does with those of sound or vision. When we speak of pain, we shall try to mean such states of consciousness as depend upon the operation of the pain nerves, in connection with which it must be remembered we most often obtain on the side of intensity our maximal experiences of the disagreeable. It is not possible at the present moment to indicate precisely how far pain nerves may be involved in the operation of the other sensory tracts, such as the visual, and therefore bow far many of our unpleasant sensory experiences, such as occasionally arise from audition, vision, etc.

Meantime, we shall follow the indication of the facts best established to-day, with a mental willingness to rehabilitate our conception whenever it may become conclusively inadequate. If affection is connected with sensory activities, it is highly probable that it will be found related to changes in these basal sensory characteristics. Relation of Affection to the Duration of Sensory Processes.

Sensory stimuli of extremely brief duration may, if we are attempting to attend to them, be somewhat unpleasant. Stimuli which are agreeable at first, such as certain tones, often become positively disagreeable if long continued, and always under such conditions become at least tedious. It must be remembered that in some instances, for example, cases of olfactory and thermal stimulation, the sense organ becomes either exhausted or adapted, as the case may be, and that for this reason the stimuli practically cease to be feltcease properly to be stimuli.

Such cases furnish exceptions to the statement above, which are exceptions in appearance only. Disagreeable stimuli when long continued become increasingly unpleasant until exhaustion sets in to relieve, often by unconsciousness, the strain upon the organism. There is, therefore, for any particular pleasure-giving stimulus a definite duration at which its possible agreeableness is at a maximum. Briefer stimulations are at least less agreeable, and longer ones become rather rapidly neutral or even unpleasant. Disagreeable stimuli probably have also a maximum unpleasantness at a definite period, but the limitations of these periods are much more difficult to determine with any approach to precision.

All sensory experiences, if continued long enough, or repeated frequently enough, tend accordingly to lose their affective characteristics and become relatively neutral. As familiar instances of this, one may cite the gradual subsidence of our interest and pleasure in the beauties of nature when year after year we live in their presence; or the gradual disappearance of our annoyance and discomfort at the noise of a great city after a few days of exposure to it.

Certain objects of a purely aesthetic character, such as statues, may, however, retain their value for feeling throughout long periods. When one has a headache the sound which otherwise might hardly be noticed seems extremely loud. Commonly, however, sensations of very weak intensity are either indifferent or slightly exasperating and unpleasant; those of moderate intensity are ordinarily agreeable, and those of high intensity are usually unpleasant.

Owing to the obvious connection of the sensory attributes of duration and intensity, we shall expect that affection will show variations in keeping with the relation between these two. A very brief stimulus of moderate intensity may affect the nervous system in a very slight degree. A moderate stimulus on the other hand, if long continued, may result in very intense neural activity' and so be accompanied finally by unpleasant affective tone, rather than by the agreeableness which generally belongs to moderate stimulation. Affection and Extensity of Sensations.

Elements Of Consciousness

A colour which seems to us beautiful, when a sufficient amount of it is presented to us, may become indifferent when its extent is very much diminished. This consists, practically, however, in substituting a moderate intensity of visual stimulation for one of very restricted intensity. On the side of extensity the variations in affective reactions are most important in connection with the perception of form, and to this feature we shall refer at a later point. Comparison of Affection With Sensation. It apparently possesses only two fundamental qualities, agreeableness and disagreeableness, which shade through an imaginary zero point into one another.

On both sides of this zero point there are ranges of conscious experience whose affective character we cannot introspectively verify with confidence, and we may call this zone the region of neutral affective tone. But we must not suppose that this involves a genuine third elementary quality of affection.

Apart from these two qualities, it seems probable that the only variations in affection itself are those which arise from differences in its intensity and duration. The more intimate phases of the changes dependent upon the shifting relations among these attributes we cannot at present enter upon. Wundt, however, maintains that an indefinite number of qualities of agreeableness and disagreeableness exist. Conclusive introspective proof bearing upon the matter is obviously difficult to obtain. Affection and Ideational Processes.

San Gabriel Unitarian Universalist Fellowship

But affection is of course a frequent companion of ideational processes, and it is, indeed, in this sphere that it gains its greatest value for the highest types of human beings. We must, therefore, attempt to discover the main conditions under which it comes to light among ideas. We may conveniently take as the basis of our examination the processes which we analysed under the several headings of memory, imagination, and reasoning.

Fortunately we shall find that the principles governing affection in these different cases are essentially identical. That our memories are sometimes agreeable and sometimes disagreeable needs only to be mentioned to be recognised as true. Oddly enough, as was long ago remarked, the memory of sorrow is often a joy to us, and the converse is equally true. It may, or it may not, be similar. Moreover, either the original event or the recalling of it may be affectively neutral. What then determines the affective accompaniment of any specific act of memory? In a general way we may reply, the special conditions at the moment of recall.

In a more detailed way we may say whatever furthers conscious activity at the moment in progress will be felt as agreeable, whatever impedes such activities will be felt as disagreeable. An illustration or two may help to make this clearer. At the first shop he gives an order, and upon putting his band into his pocket to get his purse and pay his bill he finds that the purse is gone. The purse contained a considerable sum of money, and a search through the outlying and generally unused pockets of the owner fails to disclose it. The immediate effect of this discovery is distinctly and unmistakably disagreeable.

The matter in hand is evidently checked and broken up. Furthermore, the execution of various other cherished plans is instantly felt to be endangered. Thereupon, the victim turns his attention to the possible whereabouts of the purse. Suddenly it occurs to him that just before leaving home he changed his coat, and instantly the fate of the purse is clear to him. It is serenely resting in the pocket of the coat lie previously had on, which is now in his closet.

The result of this memory process is one of vivid pleasure. The business in hand can now go on. It may involve a trip home again, but at all events the money is still available, and the whole experience promptly becomes one of agreeable relief. Suppose that in this same case, instead of being able to recall the circumstances assuring him of the safety of the purse, our illustrative individual had failed to find any such. In this case the memory process would augment the unpleasantness of the original discovery of the loss.

The activity which he had planned for himself would appear more than ever thwarted, and the disagreeableness of the experience might be so intense as to impress itself on his mind for many days to come.

- A Few Words About Theme

- Beauchamps Career — Volume 2

- A Child Of Her Own (Mills & Boon Vintage Desire)

- A Film Actors Technique

- WHATS YOUR PLAN - Manage Side Effects of Chemo & Other Cancer Treatments

- Le Dernier Jour dun condamné (Classiques) (French Edition)

- Monsieur Gendre : Le roman vrai de laffaire Botton (Documents) (French Edition)